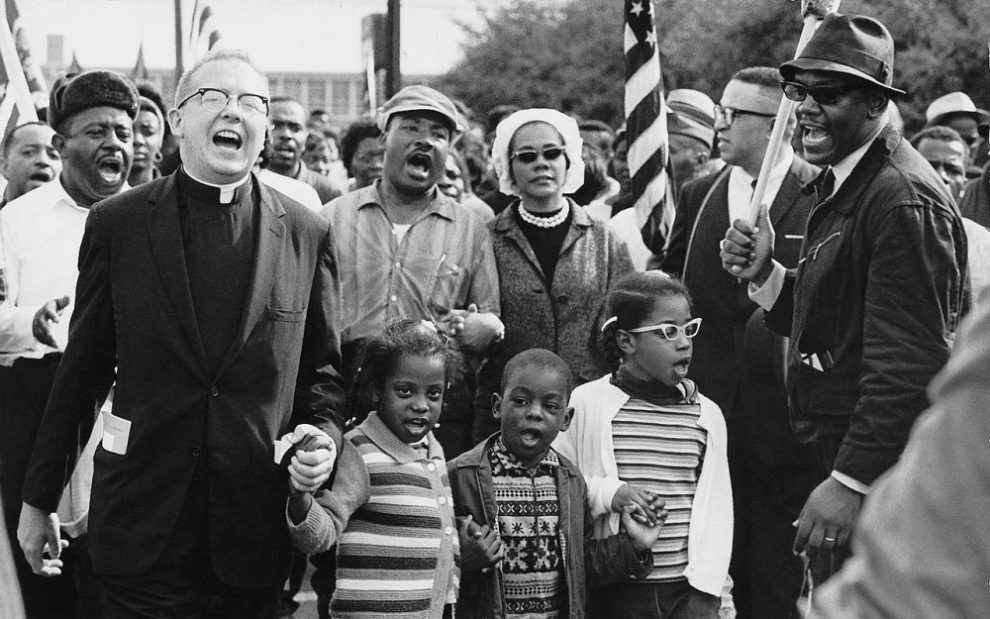

When remembering the revolutionary period in American history known as the civil rights movement—a nonviolent social and political movement and campaign that set out to abolish legalized institutional racial segregation, discrimination, and disenfranchisement throughout the United States and lasted from 1954 to 1968—several key figures come to mind. Perhaps it is Thurgood Marshall and his groundbreaking work on the Supreme Court case that came to be known as Brown vs. Board of Education; Rosa Parks, whose unwillingness to give up her seat on the bus played a pivotal role in the Montgomery bus boycott; or maybe the most prominent figure, pastor and theologian Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. who was a key participant and organizer for the March on Washington, the Selma to Montgomery marches, and the Poor People’s Campaign to name just a few. But what often doesn’t happen in our recollections of this tumultuous and challenging time is considering the role that many Catholics, specifically Black Catholic activists, played in the fight for civil rights and eventually the transformational shift into movements for Black Power, which would provide the necessary spark for the birth of the “movement within a movement”: the rise of a Black Catholic Revolution.

Prior to this revolution, several notable Black Catholic activists were leading the charge for civil rights in their respective cities, states, and dioceses. For instance, Norman C. Francis, the first Black Catholic graduate of Loyola University New Orleans College of Law, broke down many racial barriers in Catholic institutions of higher education in the United States during this period. He did so in his early law practice in New Orleans; as an administrator at Xavier University; and as Xavier’s president during the height of the Black Catholic Movement. In 1961, he provided shelter at Xavier University for the “Freedom Riders” arriving in New Orleans; and in the late 1960s, Francis played a significant role in the Black Catholic Movement, culminating in 1980 with the founding of the Institute for Black Catholic Studies at Xavier University.

Additionally, Franciscan Sister of Mary Mary Antona Ebo, a Black Catholic nun from St. Louis, left a lasting impact on social justice and civil rights, becoming the only African American sister to march with the Rev. Dr. King at Selma on March 10, 1965. Initially deciding against traveling down to Alabama, Sister Ebo changed her mind after the events of “Bloody Sunday”—when state troopers assaulted protestors with clubs and tear gas—making the heroic decision to join her fellow brothers and sisters in the fight for their freedom. She is famously remembered telling the crowd concerning her presence that, “I’m here because I’m a Negro, a nun, a Catholic, and because I want to bear witness.”

It would not be until the late 1960s, however, that this Black Catholic “movement within a movement” would really take off after the assassination of Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. on April 4, 1968. By this time, the United States Catholic Church was undergoing a transformative moment tied to the militant rhetoric and realities of the emerging Black Power movement along with the changes initiated by the Second Vatican Council. Historian Matthew J. Cressler notes that the assassination of Rev. Dr. King actually marked the beginning, rather than the end, of Black Catholic freedom struggles. Black Power galvanized Black Catholic activists, many Black priests and nuns taking heed of the self-determinist message advanced by the movement. In fact, Black Power so transformed Black Catholics that some argued that Black parishes needed Black clergy members to lead them while others joined forces with the Chicago branch of the Black Panther Party.

Cressler notes that less than two weeks after the assassination of Rev. Dr. King, many Black clergy and religious came together in Detroit to discuss the conditions in the Black community and subsequently the role of the Catholic Church in those communities, along with the utilization of Black clergy and the discernment of Black vocations. Their inaugural statement indicted the church as “primarily a white racist institution” that has solely devoted itself to “white society and is definitely a part of that society.” Moreover, these recommendations to church leaders called for the establishment of a Black Catholic vicarate and the appointment of an episcopal vicar for Black Catholics in the United States; the increased recruitment of African Americans to the priesthood along with the creation of a Black diaconate; an inclusion of Black history and culture in seminary curricula; the incorporation of Black culture into the liturgy; and the creation of a national office for Black Catholics within the framework of the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops. This meeting would mark the formation of the National Black Catholic Clergy Caucus (NBCCC).

Sister of Mercy Martin de Porres Grey later coined this moment as the beginning of the Black Catholic Movement, a revolution that commenced the onset of “Black consciousness for Black Catholics.” In response to her exclusion at the initial meeting by the priests, Sister Grey spearheaded the founding of the National Black Sisters’ Conference (NBSC) in Pittsburgh. These Black women pledged themselves “to work unceasingly for the liberation of [B]lack people” and further denounced “expressions of individual and institutional racism found in our society and within our church…[racism being] categorically evil and inimical to the freedom of all [people] everywhere, and particularly destructive of [B]lack people in America.” The sister’s contributions also called for increased participation in community action and the expansion of support for programs that encourage the growth of Black leadership within the church.

With the birth of the NBCCC and the NBSC, the Black Catholic Movement gave rise to other prominent Black Catholic organizations, including The National Office of Black Catholics founded in 1970 by Marist Father Joseph M. Davis; the National Black Seminarians Conference in 1970; the National Black Catholic Lay Caucus in 1978; and the National Association of Black Catholic Administrators in 1978 which led to the eventual formation of the Black Catholic Theological Symposium. In October 1978—10 years after the formation of the NBCCC—the Black Catholic Theological Symposium convened in Baltimore under the leadership of Fransciscan Father Thaddeus Posey. More than 30 papers were presented at the conference, discussing the development of Black Catholic theological education initiatives and pastoral responses to the “Black condition” within the U.S. Catholic Church.

Father Posey’s groundbreaking contribution involved a proposal for the creation of an educational institute focused on the pastoral and intellectual needs of Black Catholics, to be presented to the board of directors of the NBCCC. With the board’s approval, Father Posey met with Norman C. Francis—president of Xavier University, the only historically Black Catholic university in the country—to discuss housing the institute on Xavier’s campus. In the summer of 1980, the Institute for Black Catholic Studies was officially launched with 16 students enrolled. While Father Posey served as the director of the program, other notable Black Catholic scholars served as faculty, including Benedictine Father Cyprian Davis, Toinette M. Eugene, and Congregation of the Blessed Sacrament Father Joseph Nearon.

This month, Black Catholics activists and their allies remember the movement that made possible the work which we undertake today, both in the academic and pastoral sectors of the church. Without the witness of these elders and ancestors, we would have surely lost our way along with a hopeful orientation toward the future. Without them, we would have never dared to proclaim the authenticity of our Blackness and the trueness of our Catholic faith.

Add comment