“Can the church we love, love us back?” asks Ansel Augustine in the subtitle to his new book, Leveling the Praying Field. Despite document after document on the sin of racism, there have been no substantive changes to the problem of racial inequity within the U.S. Catholic Church. No attempts to shift the balance of power. No attempts for reparations or reconciliation in the face of centuries of hurt.

Augustine weaves together his own personal experience as a youth minister and resident of New Orleans with historical and theological context to argue that it is past time for the church to go beyond documents and empty words. Indeed, the future of the Catholic Church depends on it: Young people are leaving the church in record numbers, in large part because they don’t see the church working toward racial justice or to end other inequities.

Augustine refers to Leveling the Praying Field as a “love letter to the church,” but it is also a love letter to those who make up the church, especially the youth and young adults who will be its next leaders. He not only offers a blueprint for youth ministers, pastors, and anyone working with young adults on how to “walk the walk” of racial justice, but he also stands as a role model for any young person struggling with how to stay Catholic in the face of racism, sexism, homophobia, or any ism within the church. This is your church, Augustine tells readers through the stories, reflections, and prayers offered in this volume. Don’t be afraid to take up space and to show up as your authentic self.

Where did the title of your book come from?

Leveling the Praying Field is a play on “leveling the playing field,” which is about creating opportunities and equity for people who have been marginalized by institutional, systemic, or even personal acts. In this book, I talk about leveling the praying field, because unfortunately in our Catholic Church people of color, specifically Black Catholics and even more specifically African American Catholics, have been left behind. We’ve been here from the founding of the church: Both free people of color and our enslaved ancestors put in the work to help dioceses flourish. But when you look at leadership, where the attention is given in dioceses, what parishes and schools are closing, or who is leaving the church in droves, it’s Black Catholics. Many times the only attention given to Black issues is when there is a PR crisis or national or diocesan tragedy that needs to be addressed.

What would it look like to level the praying field—to make the church truly equitable?

I was the youth minister at St. Peter Claver, my home parish, which is in Treme, a neighborhood in New Orleans and the oldest Black neighborhood in the country. Until about four years ago, the parish had an Afrocentric Catholic school. The school had not only Catholic symbols and images, but also intentionally Black symbols and images. The kids wore kente cloth as part of their school uniform. There was an Afrocentric style of worship. The students saw that they were holy and part of God’s salvation story.

When I imagine a church that’s equitable, I want to create opportunities for the youth and young adults from my community to live their authentic lives and have the church support that, no matter what it looks like. I see my white Catholic colleagues and friends are able to be free in the church, but Black Catholics always have to put on a mask or be reserved in order to have open and honest conversations. I feel that sometimes we make people uncomfortable when we come as our authentic selves.

I wish the church would accept us for who we are, not only when it’s time for Black Catholic History Month or when we’re doing some special Mass, but on a regular basis. I wish we could come to our church as fully functioning authentic African American Catholics and not be judged for it, seen as second-class Catholics, or seen as unprofessional because we come in our own authentic ways.

This book is a love letter to the Catholic Church. That’s why my mentor, Father Bryan Massingale, wrote the foreword and Bishop Fernand J. Cheri III, the auxiliary bishop of New Orleans, wrote the afterword. I hope that this book empowers other voices that are on the margins and gets them to the table so that the gifts of the Black Catholic community are heard and appreciated by the church as a whole, to paraphrase the words of Sister Thea Bowman.

Can you talk more about what you mean when you say this book is a “love letter to the church”?

I’ve had the police called on me and my kids when we attended meetings at suburban parishes. I’ve dealt with racist comments or even actions at national events and meetings. And yet, I love the church. It has given me so much. My own community of New Orleans is a Black and Catholic city. These things go hand in hand; they aren’t separate. For many people of color, especially African Americans, faith and secular life are one and the same. Our faith walks with us.

In 1989, Sister Thea Bowman addressed the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops (USCCB) and told them to look at Black Catholics as a gift to be treasured, not as a burden to be dealt with. I want the church to see the gifts that we bring, that our young people bring. Gen Z and Millennials and the ones that come after them are shaping a different world right now. Are we as a church ready to meet them?

That’s the work I’ve been doing. After Hurricane Katrina, I came home and was trying to rebuild, and I started working for the diocesan youth office to diversify the outreach to Black parishes. And what I have seen is that when this work is authentically done, there is such love, power, and fruits of the Spirit that come from the genuine connections that form.

I want to share those experiences of love that can happen when we authentically see that our brother or sister may look differently than us, may speak differently than us, may live in a different part of town or have a different socioeconomic status than us and yet is still made in the image and likeness of God. Pope Francis challenges us on a regular basis to see Christ on the peripheries. To me that’s the love letter: When you love somebody or something, you challenge them to be better. If you didn’t care, you wouldn’t do this type of work.

Who do you hope will read the book?

After the murder of George Floyd, I realized that there weren’t any Catholic resources for my colleagues in young adult or campus ministry to talk about racism from a Catholic perspective. So that’s what I’m trying to accomplish in this book. Youth and young adults were already having really honest and open discussions outside the church, and I wanted there to be a resource for having these same conversations within Catholic circles. I needed to create a resource that could bridge their faith life with what they were doing in the streets.

There is a growing realization that youth and young adults are hungering for the church to be involved in justice movements in authentic ways. What is the hurdle to doing so?

Pope Francis says somewhere—I believe in Christus Vivit—that one of the most sinful phrases in the church is, “We’ve always done it this way.” And I think this gets in the way of being present to young adults. Are we listening to youth and young adults, or are we putting them in silos, with our campus ministry over here and all the other ministries over there? Are there relationships and connections across and among these different groups?

My dream for youth ministry is to leave the next generation a better way to take over, and to prepare to hand over the baton so they can run with it in their own unique ways. I think the challenge for us as a church is to examine how we’re engaging these spaces and places to hear the voices of young adults. That’s what it’s about.

When we look at what Jesus Christ modeled for us, it was how to listen to the least of the people. And who are the least in our church right now? It’s our youth and young adults. Their voices are not being heard in the church, so they are leaving and shouting in other spaces. And yet, they want to see the church walk the walk. They want the church to do the work. And if they don’t see it, well, they’ll find it elsewhere or create it on their own.

Can you give an example of a program or ministry that has been really successful at engaging youth?

After Hurricane Katrina, Archbishop Emeritus Alfred Hughes in New Orleans hired me to be the coordinator of Black Catholic Youth and Young Adult Ministry. He wanted me to figure out how to better connect our Black Catholic parishes, the three Black Catholic high schools, the Knights and Ladies of Peter Claver, and Xavier University of Louisiana—the only Catholic HBCU (Historically Black College and University) in the country.

To do that, I engaged in open and honest conversations about why people weren’t involved. I invited my office staff, which was predominantly white; parish youth ministers; campus ministers from Xavier and the Catholic high schools; coaches and mentors; and young people. Our numbers started growing. The diocesan youth conference events went from having five Black youth in a group of 120 to 60.

I think what worked and what needs to continue is getting people to the table to have those authentic and uncomfortable conversations. We’re good at having conversations with people we like or who think like us—even if they don’t look like us. But as a church, how do we engage those who may rock the boat, who may have not-so-nice things to say about ministry? How do we make them feel welcome at the table? How are we called to move forward in ministry together and build the kingdom of God here on Earth?

Do you have any suggestions for how to start having these tough, uncomfortable conversations?

Father Bryan Massingale has told me so many times that one of the challenges is that we don’t want to make white people uncomfortable. We don’t want to make the white power structure uncomfortable. Many of my friends, including myself, have been affected by racism from leadership in various ways, shapes, or forms. People have been hurt by the church, and nobody is really held accountable. When I get complaints to my office about a racial incident in my community, I don’t have anywhere to send those phone calls. Many times, because I represent the diocese, I become a punching bag: There’s no one to walk with me in that journey.

Because of the hierarchical structure of the church, I think any solution has to come from leadership. We have so many documents from the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops (USCCB) about anti-racism. But we can talk about it endlessly: How are we going to hold people accountable?

Part of this is coalition building. There are so many anti-racist groups in parishes and schools around the country. How do we make these groups more well known? How do we connect these smaller groups on a bigger level? What would it look like for the USCCB to have a National Office Against Racism?

I don’t want to knock the USCCB, but for those of us on the ground and in the trenches, it is clear that young adults want to see more than listening. They don’t want to read another document. They want to know how the church is going to address the inequities that still exist within the church.

What keeps you Catholic, despite the very real wounds the Catholic Church has dealt?

For me, St. Peter Claver and our school have been real sources of strength. When I would get overwhelmed by my diocesan work, I would go to St. Peter Claver school and just be with those elementary school kids. They didn’t know me as Dr. Ansel Augustine, they knew me as Big Chief Toilet Paper—that was my dj name. Youth and young adults have always been what inspires me and keeps me Catholic.

It’s not about going to another meeting or being on another panel: It’s about doing the work in the community. I get such hope from watching these young adults fight for the right thing in the streets and in our communities. I just pray that whatever I’ve contributed helps them keep fighting the good fight. Catholics are called not to do the easy thing, but the right and just thing. That’s what Christ did. It wasn’t easy to die on the cross. And not to say I’m Jesus, but I’m his child, and that means I’m called to do the right and just thing. Even if I’m standing alone. Even if I’m unpopular.

After focusing much of your book on action and forming new relationships, you end with a prayer service. Why did you decide to include this?

One of the tenets of Jesuit spirituality—and of Black spirituality—is seeing God in all things. I look at life and everyday work as a form of prayer. For Catholics, everything we do is led by prayer—including fighting the injustices both outside our community and in our church. I could be screaming at the top of my lungs about the injustices I see, but it isn’t about me—it’s about what God does through me.

When we do the work of racial justice, we’re doing God’s work. It’s not about me or my own agenda or the book I’ve written—it’s what God has called us to do.

What are three things you’d like young adults to take away from your book?

First, to know that nothing in this book is made up. I hope the stories I tell in this book inspire or empower people to know they’re not alone. But even if they can’t relate, I hope this book motivates people to act and to see what injustices they notice in their own spaces and places. Sin is real: It may not be exactly what I’ve experienced or described in this book, but it is prevalent in our world. Sometimes that sinfulness doesn’t manifest in racism or racial differences. It may be around gender identity, homophobia, classism—all these other isms that divide us. So number one: Search out the injustices in your own space and take concrete action.

Two: Remember that this is a love letter to the church. I see the church as my space, even though it may not always love me back in the same way. The church is your space. Defend it. It is your space, and you deserve to be here.

Three: Empower others. See who is on the peripheries, especially if you come from a place of privilege. And see how you can empower their voices in the work that needs to be done to create a just society.

This article also appears in the February 2023 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 88, No. 2, pages 26-30). Click here to subscribe to the magazine.

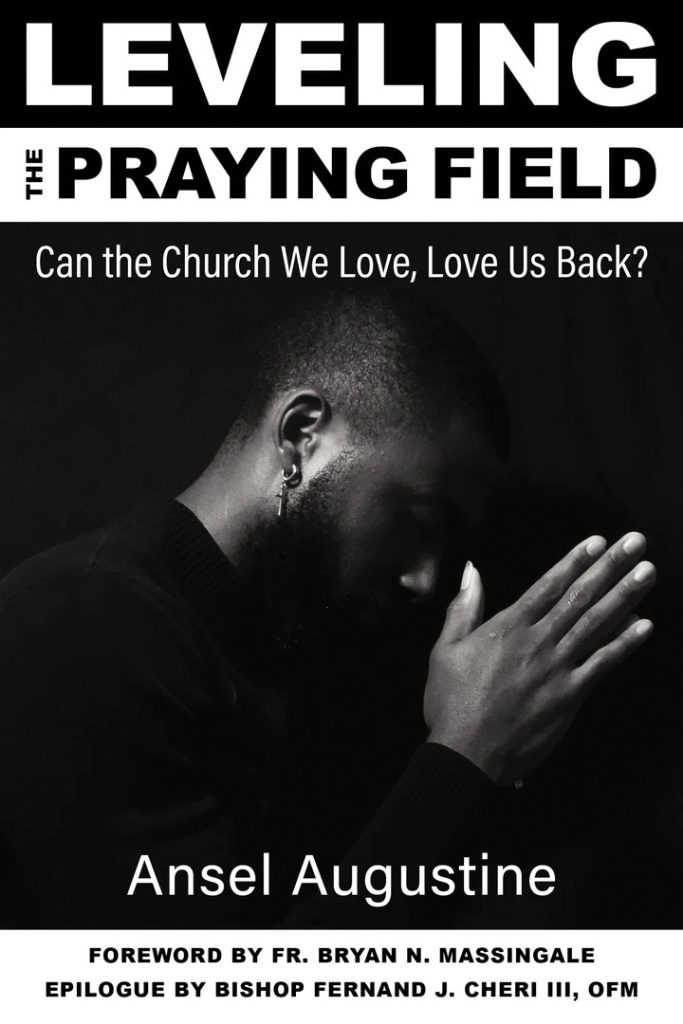

Image: Unsplash/Channel 82

Add comment