“Black Lives Matter to God and to Us,” reads a large banner hanging over the entryway to the United Catholic Youth Ministries (UCYM) staff workspaces on the top floor of St. Nicholas school and parish in Evanston, Illinois. Through the doorway left of the banner is a meeting room with long tables and windows that overlook the parish garden and tree branches. A Pride flag hangs next to a crucifix above a counter filled with potted plants, a statue of Our Lady of Guadalupe, and a poster of St. Óscar Romero.

It is a lived-in space, with sunlight spilling through windows onto shelves of canvases. A waving fox colored in orange marker lives on the fridge, and a corkboard is home to flyers for various UCYM groups for interfaith, LGBTQ, and Latino/a communities and a leadership academy.

Evanston’s four parishes—St. Nicholas, St. Joan of Arc, St. Mary, and St. Athanasius—which merged into two parishes as of July 2022—came together in 2016 to think about how they were going to support their youth and young adults, knowing Renew My Church—an initiative by the Archdiocese of Chicago to regroup or combine parishes—was going to transform the Catholic landscape in the city in the coming years. UCYM was born from these conversations and launched in 2017.

James Holzhauer-Chuckas, UCYM’s senior director, says UCYM has four main focus areas: youth ministry, young adult ministry, campus ministry, and Hispanic ministry, which includes quinceañera ministry. The groups have weekly Saturday gatherings, retreats, small group sharing, and social events.

The canvases in the meeting space are from a recent Saturday meeting in which teens drew images of God. One has a silhouette of a person surrounded by pine trees, looking at the moon with their pets. Another has a smiling stick figure orbited by colorful items.

“We have been talking to [teens] about their image of God and putting that onto a canvas, demonstrating that every canvas looks differently because everybody has this different experience and image of God. No one is wrong,” Holzhauer-Chuckas says.

This emphasis on each person’s dignity, and affirmation of teens’ identities and beliefs, is part of UCYM’s mission of creating space for youth to “connect their faith to the sociopolitical environment all around them,” says Mary Miro, a young adult volunteer at UCYM. The organization is explicit about striving to create inclusive communities that are anti-racist and anti-oppressive within Evanston’s Catholic landscape and in the broader community.

“What UCYM is trying to do is think about 21st-century Catholicism in a global, anticolonialist lens,” says Miro. “If we do not explore those questions and challenge the institutional Catholic Church to do better, we are hitting a dead end.”

Having Black Lives Matter and Pride flags in UCYM’s space, Holzhauer-Chuckas says, isn’t a political statement—they “exist here not because we’re trying to go against church teaching, but because people who are Catholic who do identify as LGBTQ or who are Black, they have a place here,” he says. “[UCYM is working to] try to get our name out there more as a place people can count on, as a place youth can feel safe.”

Renew My Church

UCYM working with and across four parishes was a model created with Renew My Church in mind. The organization works to unite Evanston’s four Catholic communities in an intentional way even though they have “widely different realities,” Holzhauer-Chuckas says. This has been a challenge, especially for adults who have been more entrenched in the life of a singular parish for years. But “our young people,” Holzhauer-Chuckas says, “don’t see parish boundaries the same way” as adults often do.

“What Renew My Church is talking about is unity,” he says. “It’s not merging things, it’s not corporate talk, it’s spiritual in nature. And I think our young people really get that. They’re so unified through school and sports and all these things that they walk into a youth group and are like, ‘Hey, I know those people!’ And it’s not so weird.”

“It’s good to aspire to connect people in a way they haven’t been connected before,” says Jason McKean, a parishioner at St. Joan of Arc and volunteer youth group leader. “Evanston is a pretty segregated community. [There’s] a part of town that is primarily African American, definitely a part of town that has a larger Latino/a population, a part of town that has a larger Eastern European population. Those areas are really divided, and that division shows up in the churches.”

Parishioners at St. Joan of Arc and St. Athanasius are predominantly white and less socioeconomically diverse than those at St. Nicholas and St. Mary, McKean says. “To have those four populations interacting in a way that they would not normally have to could be a real benefit for people’s social connections and their faith,” he says. “They could see [faith] lived out in different ways or with different priorities.”

Staff members at UCYM celebrate and welcome Evanston’s diversity—“racially, ethnically, and in terms of age,” says Mirka Gallo, UCYM’s administrative assistant, who joined the staff in 2019 after participating in their young adult ministries. UCYM partners with the group Evanston Latinos and Evanston’s interfaith community, which allows it to move outside of solely Catholic spaces.

Finding ways “that our Catholic faith can address segregation is really important,” McKean says. “It’s already becoming an important part of [UCYM’s] mission and direction, and actually doing the work to get there is going to be really positive.”

Reparations in Evanston

In 2019 Evanston became the first city in the United States to approve a local reparations program. The Evanston City Council passed two ordinances supporting reparations. One ordinance, the monetary establishment of reparation payments up to $10 million to Black residents, focuses on housing. The other is an acknowledgment of how systemic racism and redlining played into the city’s residential zoning between 1919 and 1969.

The reparation payments give $25,000 to Black residents who lived in Evanston between 1919 and 1969. These funds focus on restorative housing to help repair homes or pay down mortgages, according to WBEZ, Chicago’s NPR news station. The funds are mainly coming from cannabis tax receipts, which average $250,000 a year in Evanston, allowing the city to monetarily help 16 people at a time once or twice a year. In addition, the Evanston Reparations Community Fund nonprofit was created to continue the ongoing funding of reparations after city funding is exhausted.

Evanston’s interfaith community is involved in and committed to supporting local reparations. The interfaith clergy group comprises 17 faith communities, including UCYM. It is the “first nongovernmental institution in the city to join the local reparations movement,” according to Evanston RoundTable.

Holzhauer-Chuckas is the representative for UCYM and Evanston’s Catholic parishes in the interfaith reparations committee. The faith communities have pledged to support local reparations through fundraising and community education, each in their own way and specific to their communities.

The interfaith groups have committed financially, relationally, and educationally to “truth telling and story sharing—to do the real soul work of reparations,” according to the Rev. Eileen Wiviott, senior minister at the Unitarian Church of Evanston.

Historically, although Evanston has a rich history of social justice activism, “faith communities [in Evanston] have been complicit or silent in the face of injustice,” Wiviott says. “We’re called by our faith, regardless of what faith community you belong to and what your tenets are, to the importance of justice and caring for our neighbor and centering the needs of those who are most marginalized in our community.”

The issues of “redlining, discriminatory housing, and putting people into particular areas and denying people the ability to raise and generate generational wealth” need to be addressed by faith leaders, she says.

For Holzhauer-Chuckas, committing UCYM and Evanston’s Catholic parishes to the city’s local reparations is part of what the Catechism of the Catholic Church “demands of us.”

“When there are things going on that pertain to needs for healing and repair and reconciliation, we have to be on the front lines,” he says. “Who better to do that and lead that than our youth?”

Most of the clergy members committing to support reparations are white, Wiviott says. “It is the congregations of predominantly white folks that need to do this work of reparations,” she says. “We speak to the clergy of predominantly Black congregations to say, ‘This is what we’re pledging to you.’ We didn’t do that outside of relationship.”

Working with other faith traditions and houses of worship in Evanston enriches UCYM, Holzhauer-Chuckas says. “A lot of the houses of worship that are part of the interfaith reparations program are just the best,” he says. “You’ve got people who are on this gospel-centered mission of reconciliation and healing and repair. That’s exactly what we want to be part of too.”

Because Evanston’s local reparations program is the first of its kind in the United States, “all eyes are on Evanston and what we are doing,” Wiviott says. “Nobody is saying this is the perfect answer. But they are saying, this is a powerful and positive step forward. The feedback we’ve gotten is that the faith community’s support of it is a really striking and powerful statement that has meaning and value and weight.”

This month, on Martin Luther King Jr. weekend, the interfaith communities that have pledged their support of reparations made a public statement about collective funds raised and the efforts of education that have been accomplished since they formally pledged their support in June 2022. Their support will not end in 2023 but will continue for years to come.

“We are committed and ongoing,” Wiviott says, “not just with our actions but with our hearts and spirits.”

UCYM is in the beginning stages of developing an interfaith youth group that would participate with Evanston’s interfaith community. Youth, Holzhauer-Chuckas says, often “know more than a lot of us adults [do about justice and anti-racism]. They are so knowledgeable and find good information and are able to share it and educate us.”

Although UCYM has committed to fundraising for the reparations fund and educating Catholics around reparations, Holzhauer-Chuckas doesn’t want it to stop there.

“There are opportunities for spiritual growth around this, as well as acknowledging and understanding the history of religious affiliation with things that were done in the past,” he says. “There’s a need for the Catholic Church to be part of these conversations and movements, to show people that we exist in this world too. We don’t just exist in a bubble.”

Inclusive communities

UCYM’s involvement in Evanston’s reparations initiative is part of its commitment to anti-racism as an organization. UCYM started an anti-racism pilot in collaboration with the Archdiocese of Chicago’s Office of Human Dignity and Solidarity. The pilot includes training for youth and parents or guardians on anti-racism education. Right now, it is in its beginning stages.

“We at UCYM do our best to try and support anti-racism not only through the Catholic Church and religiously but in how we carry ourselves individually and as a staff,” Gallo says. “We try to look at things holistically, so while we are talking about race, we also look at the intersectionality of race in different areas. We talk about gender, sexuality, socioeconomic status, and the history of how people of color and Indigenous people have been [hurt] by the Catholic Church.”

UCYM small groups and youth groups have open conversations and provide space for youth and young adults to process frustration with injustice and honestly engage with the “big disconnect with what [youth] want to see [in the church] and what the church [is],” Gallo says.

“I speak for the youth that I work with at UCYM. We are in a moment in time where Gen Zers and some Millennials are really challenging the church, and saying, ‘This is what we want to see, and this is what we’re seeing, and those two things are not clicking,’ ” Gallo says.

“We have a space for [youth] to say, ‘This made me angry, or this is what I support, or this is why this is important to me,’ ” she adds. “UCYM is a space where people are not going to say, ‘OK, then just leave.’ It’s going to be, ‘OK, this is what you want to see. What can we do about it? How can I help you? Let’s brainstorm.’ ”

Encouraging and helping youth feel like they can create the church they want to see is work that Gallo feels is rare in many church spaces. Some of these small-scale actions, she says, include helping youth join a care for creation committee, become eucharistic ministers, or learn about liturgy and work with a priest to help make Mass more inclusive.

If young people can feel like they belong in UCYM spaces, “that’s a huge win,” Holzhauer-Chuckas says. “When you think of the Catholic mission and identity, that’s the goal. St. Nick’s has been a place for a long time, whether it was Friday night open gym or whatever the case may be, where teens, whether they’re Catholic or not, can feel like they can belong here.”

UCYM, with its model of crossing parish boundaries and focusing on anti-racism and inclusivity for youth specifically, is fairly unique, Holzhauer-Chuckas says. “I’ve definitely seen [Catholic youth groups that focus on anti-racism], but I don’t know how many others would say they’ve built a mission around it,” he says.

Miro says UCYM is different than other Catholic young adult groups she’s been involved in because the faith programming is less about “becoming a good Catholic” and more about being “growth-minded, not focusing on adherence to a status-quo Catholicism but on the future of the church, and how the church can be reformed and reimagined to be inclusive, outwardly anti-racist, and how to disrupt the gender binary and hierarchy of the church.”

Gallo says she thinks it is difficult to find a model like UCYM where parishes come together to create a youth ministry and are willing to collaborate.

“I think that more parishes want to look at and be like UCYM, at least in terms of their youth and young adult ministry,” Gallo says. “I feel like it has been very challenging for families to find a space in the Catholic Church that is accepting of their youth no matter where they come from. I think that some parishes can be a turnoff. We try, because we’re in such different parishes, to be inclusive to all.”

Being inclusive to all can be difficult and fraught to navigate. Recently, UCYM advertised for an LGBTQ-friendly event and got pushback by people from the church who were upset with the Pride flag on the flyer, Gallo says.

“We are very LGBTQ friendly [at UCYM],” she says. “We want that group of people to feel comfortable and confident in a space that has not always been open to them, or in a space that has been abusive toward them. [UCYM] is a great group of people that understands that it is frustrating and upsetting [to navigate pushback/homophobia] and [thinks about] how we can strategize for a longer-term struggle of acceptance.”

Being involved in reparations work in the local community is unique in Catholic parishes, mainly because Evanston is one of the first cities to have a reparations program. Gallo hopes UCYM can provide a model for other churches as more cities follow Evanston’s lead in reparations work. Catholic religious communities, including several communities of women religious, have committed to reparations efforts on a larger scale.

At UCYM meetings and in Evanston’s parishes, “we have a wide range of people with different identities,” Holzhauer-Chuckas says. “We have people who are very much more traditionally Catholic, we have people who are progressively Catholic. And people can be in the same room together. We don’t have screaming matches because people respect one another.”

There is a strong sense of togetherness among staff, volunteers, and those involved with UCYM, Gallo says. Journeying through faith together is a constant call, and youth understand community across boundaries in ways that adults often have to relearn.

In the leadership academy McKean leads, in which teens meet and get involved in a number of ways in Mass and the life of the parish, they had a session recently where McKean asked the group, “When you envision Jesus, what’s he like?”

“One teen, which I thought was brave, said, ‘It’s kind of awkward to do this, to imagine it and say it out loud,’ ” McKean says. “We are talking to somebody who we know is present but not a physical presence. It is awkward, and it’s good that you can recognize that and say it, because we can work on it together. To connect with our teens well, and be present with them, and answer their questions even when it feels really awkward, that’s the right thing to do. That’s the way you’re going to get the body of Christ to continue on.”

UCYM is committed to serving the community beyond the church and creating safe spaces for teens, even when it’s awkward.

“Christ didn’t have any boundaries to where he went, and that goes for us,” Holzhauer-Chuckas says. “It’s the gospel of Jesus. It’s just what we’re supposed to do.”

This article also appears in the January 2023 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 88, No. 1, pages 22-26). Click here to subscribe to the magazine.

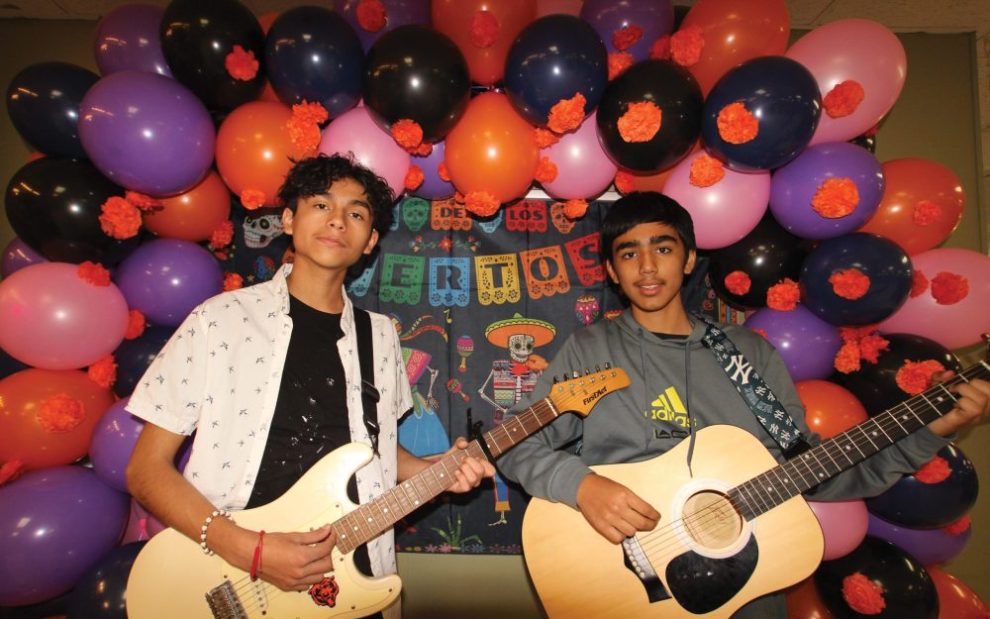

Image: Josué Ortiz

Add comment