Our names matter. Parents give names to their children to mark them as individuals who are known and loved. When people forget your name, you sense they have forgotten you. The deliberate erasure of people’s names, as was done to Holocaust victims, attempts to erase their identity as individuals. Your name matters uniquely because you matter uniquely. And in this era of increasing anonymity, our names feel more and more important.

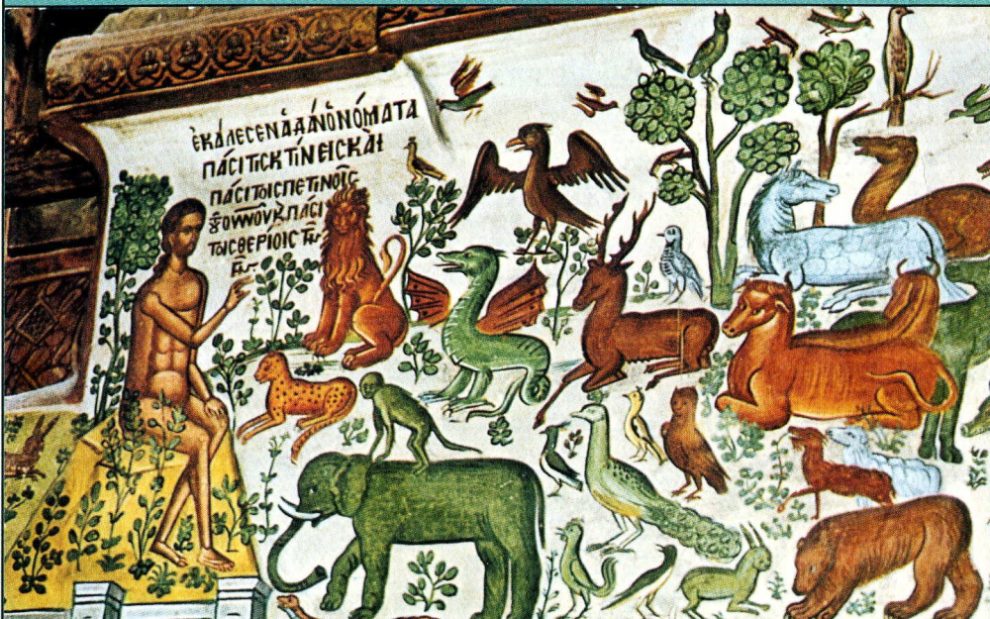

In scripture, great power and significance are attached to names. In Genesis, Adam is not only formed from the dust of the ground but shares and takes his name from the Hebrew word for it: adamah. One of his primal tasks, in turn, is to name the animals, living out his role as a priest-king who, made in the image and likeness of God who is the Word, shares in language in a uniquely human way.

Abram, which in Hebrew means “exalted father,” has his name—and therefore his very identity—changed when he enters into a covenant with God. He is renamed Abraham, which means “father of multitudes.” He is promised that his descendants will number like the stars and that through him all nations of the earth will be blessed. In other words, Abraham’s call extends down the ages to you and me because we too are known by name to God.

Similarly, the name change from Jacob (“deceiver”) to Israel (“he who struggles with God”) compacts the entire mystical journey not only of the man but also of the struggling nation that takes its name from him. Through the name change, the Israelites are transformed from a “stiff-necked people” (Exod. 32:9) constantly rebelling against God into God’s chosen people.

So central are names to the Book of Exodus that its Hebrew title is “These Are the Names”—since, as with papal encyclicals, the book takes its title from the first line. The hero of the book, Moses, has a name which means “to draw out,” referring to his being drawn out of the Nile as an infant, as well as to the core and essence of his mission to draw the Israelites out of Egypt.

But the most important name given to us in Exodus is, of course, the name of God. In God’s revelation to Moses, speaking from a burning bush, God is revealed as the self-existent one: Yahweh or I AM. The shock of this can be lost on readers, who think of names merely as labels.

To get just the slightest taste of what the revelation to Moses was like, think of some revered teacher or coach you knew in elementary school. It went without saying that they were called Mr. Smith or Ms. Allen. Then imagine that 10 years later you meet them in the checkout line at the grocery store and address them as you did when you were 10. They look at you and say, “Call me Jim” or “Call me Nancy.”

Multiply the weirdness of that moment by a billion and you have something of the shock of God’s revelation of the divine name to a people who knew him as El Shaddai (“the Almighty”). For in revealing God’s name, the infinite and all-powerful Creator enters an intimate relationship with God’s people and calls them to be family. God’s people receive the dignity of God’s name.

That’s why God tells the Israelites (and us), “You shall not make wrongful use of the name of the Lord your God” (Exo. 20:7). This means more than just “Don’t cuss.” It means that God’s people, as a priestly nation representing God, are not to insult God and mislead other human beings by doing things God never commanded or refusing to do what God has commanded. We are not to call on God as witness to our lies or give scandal by behaving immorally and saying that it’s all fine since we are chosen, though we have succumbed to this temptation throughout history, resulting in the lament: “The name of God is blasphemed among the gentiles because of you” (Rom. 2:24).

The revelation of God as I AM—the self-existent one who needs nothing, creates from nothing out of love, graciously calls humans into relationship, and stubbornly bears with them through long centuries of rebellion and trial—prefigures another phase of revelation as God comes even closer to us in the incarnation and takes an ordinary human name, Y’shua, that shows God to be not only one of us but also the “lord our salvation.”

The apostles see in Jesus and his name the fulfillment of the promise made to Abraham. Jews and Gentiles alike become children of Abraham and partakers in the divine nature through the name of Jesus, son of Abraham and Son of God. By invoking his name, we invoke Jesus to be personally present with us. And God, in turn, knows us by name—knows and loves us so intimately that, as Jesus says, the very “hairs of [our] head are all numbered” (Luke 12:7).

The affection behind these words is clear in Jesus’ playfulness with names in his relationship with his friends. John and James, given to bellicose defenses of Jesus, earn from him the nickname Boanerges (“sons of thunder”). To Simon Bar-Jonah he gives the most famous nickname of all: Peter (in Greek) or Cephas or Kefa (in Aramaic). This new name means he has become the “rock” on which Jesus builds his church. It’s also a pun on Caiaphas, the high priest of the Sanhedrin condemns Jesus. Peter, who denies Jesus three times, is reminded for the rest of his life that he failed Jesus as Caiaphas did, as well as of the power of Jesus’ love and mercy.

When Mary Magdalene stands weeping at the empty tomb and would not look at the stranger in the garden, he calls her by name, and she knows him. In that moment she also knows who she is: beloved, chosen, and called by name. In such intimacy, not in flashy miracles and thunderclaps, God speaks in a still, small voice and calls us by name.

“To everyone who conquers,” says Jesus, in the Book of Revelation (2:17), “I will give some of the hidden manna, and I will give a white stone, and on the white stone is written a new name that no one knows except the one who receives it.”

For God knows your name and mine. And that is what each of us is born to seek, because each of us is looking for the answer to the question of who we truly are. We are waiting for God to call us by name.

Image: Wikimedia Commons

Add comment