The refrain “I can’t breathe” is a rallying cry for change that has reignited movements for racial justice in the United States. But for the Rev. Angela N. Parker, the refrain also references her scholarly work on authority and biblical texts.

Parker, a womanist New Testament scholar at Mercer University’s McAfee School of Theology, is the author of If God Still Breathes, Why Can’t I? Black Lives Matter and Biblical Authority (Eerdmans). In her book, Parker details how an authoritarian understanding of the Bible has been used to oppress and control.

Parker argues that the Bible is authoritative—not authoritarian. “I think about authority as conversations with,” she says. “We get authority wrong in the way we use it, and especially in the way people who consider themselves to be the power brokers use it.”

Parker says that while many think of the Bible as the final word—a conversation ender—the Bible is more accurately a conversation starter. When we leave our personal voice and experiences out of biblical interpretation, she argues, we miss out on an important opportunity for God to breathe in and through us. Wrestling with scripture, she says, is an ongoing and important process for everyone.

“A lot of us are holding our breaths through life,” Parker says. “I don’t want to be that type of person.”

Tell us about your new book, If God Still Breathes, Why Can’t I?

As an African American woman in the United States, I’ve always had a rather conversant relationship with the Bible. What I noticed in society was not a conversant relationship with the Bible but a top-down, almost authoritarian relationship that merges people and position and leadership with biblical authority. I’m trying to find a way to have that conversation while also recognizing that Black and brown bodies are falling as a result of police violence. Is there any connection between an authoritarian nature in society and an authoritarian nature of how we understand the biblical text?

If God Still Breathes, Why Can’t I? is a play on the last words of folks such as George Floyd and Eric Garner. It also references ideas of authority in the biblical text that come from 2 Timothy 3:16–17, which talks about all scripture as theopneustos, or “God-breathed.” I’m playing with those words of “I can’t breathe” and “God-breathed” to have a conversation about authority, inerrancy, and infallibility.

We’re living in the age of COVID-19 as well, where people can’t breathe. It just seems so appropriate to be thinking about God’s creative breath and breathing in a way that’s expansive. We have to actually care for one another so that we all have an opportunity to breathe.

You talk about how you learned to read the Bible as a white male. What does that mean?

In my seminary experience, I had to learn the scholarship of the foundational thinkers in the Bible, and those foundational thinkers were heavily indebted to German idealistic scholarship. German idealism, white German scholars who were very much connected to continental philosophical thought, and that continental philosophical thought itself were part of the thinking that actually hierarchized nations. European nations became superior, and other nations such as Israel, what was termed at the beginning of continental philosophical thought as the “Orient,” and African nations were deemed as subservient.

I realized that I was learning the thinking and intellectual thoughts of German idealism and how it played into biblical interpretation. I was not so readily allowed to ask questions of the Bible from an African American context, or even from a Black Baptist tradition. I was often told that my questions were irrelevant. I had to begin with German idealism and continental philosophical thinking and formulate questions from there.

I had to push back and say, “Rudolf Bultmann is not thinking about African American Angela Parker later on, so why do I have to think about him?” The idea was that I had to begin with those questions. Any questions that were relevant to Black Baptist tradition or my context as an African American woman were too subjective, meaning I was told the objectivity was within white male scholarship.

That’s how I began to unpack: “I’m not white. I’m not male. I’m still a scholar. I have to begin to ask different questions of the biblical text than what my institutions were trying to train me in.”

Where did you first see yourself and your own faith in the Bible?

I remember vividly an indwelling of the Holy Spirit at a very young age. My mother says that when I was a baby, I would not wet my diaper when the pastor was preaching. I’d say, “You’re fooling,” but she’d say, “That’s the kind of baby you were.”

It was so ingrained: church Sunday, church Wednesday, Bible study, youth group, usher board, and choir practice. I would always see beautiful Black folks in church. I did not see women in ministry in my church. Growing up, I did not see women with the ability to preach in my church. That came later on. When I think about my faith over the years, it has grown, shaped, and developed from

the tacit acceptance of everything to, “No, let’s open up these boxes of faith and allow just who God has called me to be, to actually be.”

I was ordained right after my 30th birthday. I was ordained and licensed after going through a separation and divorce, which also made that difficult. But I was ordained as a woman. One refrain used by my pastor was, “This all would have been so much easier if you were a man.”

I think the faith that I have that’s similar to the faith of Christ—that no matter what you do, God will be there with you—has developed in such a way that it’s not necessarily just from that initial indwelling as a small child. It has expanded to something larger and bigger than I could have ever imagined. God has been faithful to me. I must continue to be faithful to God’s calling in my life, even when it seems too large sometimes for some people.

What does it mean when you say that scripture is authoritative?

When I say that scripture is authoritative, I’m talking about my ability to converse with it. I often hear people use the Bible as a conversation ender and not a conversation starter. They’ll say, “The Bible says Adam and Eve, not Adam and Steve,” and use that as a way to shut down conversations regarding same-sex marriage.

When you think about the Bible in its entirety, it’s a text written over thousands of years where different writers talk to one another. Why is it such a leap for us to think about how we enter a conversation with people who are already talking to one another? What does it mean for us to converse about these texts as we continue to be people who talk to one another and develop our faith?

I think about authority as conversations with. That’s part of the wisdom of the word authority when you think about its origins. We get authority wrong in the way we use it, and especially in the way people who consider themselves to be the power brokers use it.

What do we miss out on when we leave our personal experiences and voices out of biblical interpretation?

That’s where we miss God’s creative breath ready to breathe in us. There’s a lack of actually exhaling and inhaling again. A lot of us are holding our breaths through life. I don’t want to be that type of person. If that were the case, I would’ve never written this book. I would’ve never been an ordained woman. I would’ve never gone to seminary. I would’ve never received a Ph.D.

I would’ve never done any of those things if I had held my breath and waited for people who felt as though they had authority over me to tell me, “Go ahead and do this.” The only way I can attribute any success is by the glory of God that opens up a lot of the doors that people said would never open.

I was a single teenage mother for a long time. Oftentimes people keep the same track or story of your life in their brains long after you’ve gone through that story, closed the chapter, and begun another one. God’s creative breath that breathes in ha-adam in Genesis is the same breath that still wants to breathe in all of us who will just simply allow God to breathe in us.

You found that space to breathe through St. Paul’s letters. What was it about his writings that gave you this space?

Reading Pauline literature and thinking through Paul as a man, as a situational preacher, as someone who’s actually living in a Roman imperial slavery society, I can find little pockets in Paul that allow me to say, “This looks and feels authentic to something that I can hold on to as an African American woman,” but on the other hand, “This does not look like something that I can authentically hold on to as an African American woman.”

To be honest about that and to write in such a way that I interrogate Paul while also still upholding some elements of Paul seems healthy. It seems like a conversation with, as opposed to just wholly taking in Paul and saying, “Good,” when it’s not necessarily all good.

One place in which I agree with Paul is at the end of Galatians. He talks about bearing one another’s burdens. I argue that bearing one another’s burdens means we’re all going to make it to that final destination together.

I disagree with Paul’s language of bearing down and birthing the Galatians for Christ because he uses a Greek verb that talks about bearing down like a woman who’s bearing down in birth. When I lecture on this, usually an older white man will say, “What do you want Paul to do?” I would say to Paul, like I would say to any man who’s preaching or teaching in a church, be mindful of how you use women’s bodies and women’s experiences to make your own point about what you’re doing in your ministry. That’s what I would say to Paul, and that’s what I would say to any seminary student who happens to be in my class.

I disagree with Paul on the way he uses women’s bodies and enslaved bodies. He calls himself a slave for Christ. We have to take the use of metaphors seriously.

I often tell students that if we really believe God is as big and large as God is, and if God is actually omnipotent and all-knowing, God already knows the questions and the thoughts we have. God already knows the queries we are wrestling with. So it actually seems authentic for me to read Paul and find the pockets of agreement and disagreement, like I would do in any relationship.

Beyond just agreeing or disagreeing with a text, what does wrestling with it look like?

One thing that I do with 1 Corinthians is engage Antoinette Clark Wire, a seasoned scholar who talks about Corinthian female prophets. She argues that there are Corinthian women ministering at the time Paul is writing to the church in Corinth. Those women are praying and prophesying, as Paul writes about in 1 Corinthians 11. He tells them to pray and prophesy with their heads covered. But then later on, in 1 Corinthians 14, you get, “A woman should not speak or say anything in the church, and so she should keep silent. If she has a question, she should ask her husband at home.”

The conversation becomes this: Paul and perhaps a later redactor who added the 1 Corinthians 14 verse already know women are praying and prophesying. We already know Paul uses women in ministry, as he writes about in Romans. We know Paul acts patriarchal because in 1 Corinthians 4 he writes about coming at the Corinthians with a stick. When you get there, you say, “Do I need to come at you with a stick in order to correct you?”

What I begin to do is to say, “Paul, you act like a patriarch, but then you try to act like you’re not necessarily as patriarchal as you claim to be. You want people to imitate you. You want women to pray and prophesy, but then you want them to pray and prophesy with their heads covered, and then you want them to not pray and prophesy because now some women are talking too much.”

Then there’s the added element of sexual relations in 1 Corinthians 7, where I argue that women are probably choosing not to have sex with their husbands because then they get a little bit of power in the Holy Spirit. Pregnancy-related deaths were rampant in these congregations, so why would wives allow their husbands to get them pregnant?

All of that’s happening, and Paul is coming at us with a stick. So I come back at Paul with a stick to say, “I’m not going to let you kill me by making me have sex with my husband in 1 Corinthians 7. I still have the Holy Spirit that gives me the unction to pray and to teach and to preach, so I’m not going to keep silent. You’re coming at me with a stick? I’m coming back at you with a stick.” It’s a hard wrestling.

My first Greek exegesis of 1 Corinthians class was with 20 white men at Duke Divinity School. I remember that bodily experience of having questions of the text that my colleagues just weren’t thinking through or did not even think about. I’ve been wrestling through 1 Corinthians for a number of years and am still trying to beat Paul a little bit with that stick he threatens us with.

How do you move from personally wrestling with texts to conversations in congregations or broader communities of faith?

As I talk to different faith communities, I’m discovering the deep need for continued contextualization of our texts. We have a lot of foundational documents that we as faith communities and churches put together that are just a lot of proof texts from different parts of scripture. They tend to not allow a lot of leeway. What does it look like to be a little bit messy?

That is probably not what many congregations want to hear. They want to hear, what’s your stance on LGBTQ issues? What’s your stance on politics from the pulpit? We end up getting so lost in all of the stuff that we don’t take a love for the messiness seriously. I probably love messiness more than anything, and I have a desire to live more in the messiness and uncertainty of what it means to be faith communities together.

How can congregations make space for this messiness?

Start with the people who are tasked with preaching. One thing I used to do as a preacher is pray a prayer something like, “God, hide me and only let the cross shine through” or “God, take me away completely so that your Spirit will preach.” Over the years, I’ve realized that is impossible. I am still here.

One thing that needs to occur is allowing that messiness of a preacher, pastor, teacher to come through so that laypeople are not expecting a superspiritual, superapostle, evangelical televangelist type of person. That’s part of where the messiness needs to come in. That separates the person from the text and allows people to actually be people.

Preachers have to think about their own positions. What is your own ethnic identity? How did you grow up? How have you been taught to read this text? If you were to read the text from the underside of society, how would you do that? Where do you need to understand the cultural background of this text so that you don’t hyperspiritualize and do damage?

What does it mean to sit down and intentionally preach from one text and work on that text for an extended period of time in a sermon, to lay it out and allow folks to see the intensity of what it means to do deep exegetical work and allow that to come out in a preaching moment? That’s what I hope for.

This article also appears in the March 2022 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 87, No. 3, pages 16-20). Click here to subscribe to the magazine.

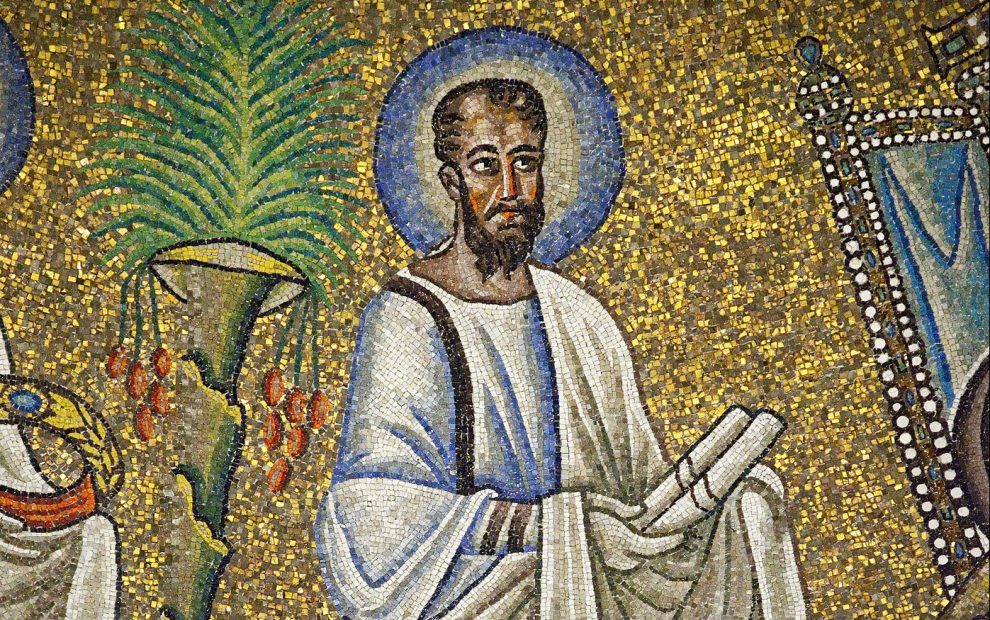

Image: Wikimedia Commons/Ввласенко [CC BY SA 3.0]

Add comment