Towering intellect. Contemplative religious. Loyal friend. Such were a few of the many sides of Edith Stein. She’s also like an older sister to me.

During her lifetime in Germany, the country reeled from the death, destruction, and humiliating defeat of World War I, the excesses of the Roaring Twenties, and the dark hate of Nazi control. Stein’s search for truth would unfold amid the chaos of that tottering world.

She was born to Jewish parents on October 12, 1891—Yom Kippur, the Jewish Day of Atonement—in Breslau, Germany (now Wroclaw, Poland). At 14 she simply “stopped praying,” and it would be years before she came to grips with her need for God. Stein’s inner struggles continued until 1921, when she happened upon the autobiography of St. Teresa of Ávila during a visit with her friend, Hedwig Conrad-Martius. Her immediate response was to buy a prayer book and a catechism.

Approaching a parish priest, she asked for baptism, only to be met with hesitation. Stein then requested the priest test her, and she was baptized on January 1, 1922.

Soon after, she wanted to enter religious life, but she chose to put her plans on hold due to her mother’s painful reaction to her conversion. She continued writing and speaking on philosophy until 1933, when Hitler’s laws prevented Jews from teaching. Stein saw this as her opportunity to enter the cloistered Carmelite convent in Cologne, taking the religious name Teresa Benedicta of the Cross.

In 1938 Stein was sent to a convent in Echt, Netherlands due to the increasing danger in Germany. She was not safe even there, as the Nazis soon occupied the country. The Germans responded to a Dutch bishops’ letter condemning anti-Jewish measures by arresting of a large group of Jewish Catholics—including Stein and her sister Rosa—who were taken to Auschwitz. They both died there on August 9, 1942.

Even though Stein died some seven years before I was born, she nonetheless has become a presence in my life—like an older sister I never had. Unsatisfied with cookie-cutter books about her, I decided to research her life, hoping to write a book. I plunged in, not knowing that I would have to navigate the equivalent of a religious minefield.

Stein’s life reminds me that greatness demands more than easy answers.

Advertisement

Stein’s canonization in 1998 wasn’t welcomed by many Jewish people because she had left the Jewish faith, an apostasy that carries with it a profound sense of betrayal. Both Jewish and Christian critics have said that calling Stein a martyr of the Catholic faith diminished her persecution as a Jew and the memory of the Holocaust.

When I discovered the backlash to her conversion from Judaism to Catholicism, I decided to read everything—both pro and con. In fact, I often found the hypercritical articles easier to read than the purple prose that turned someone I respected greatly into a plastic holy card.

During my reading I discovered someone real, someone who, even with a towering intellect, had flaws and insecurities. Moreover, I was touched with her struggle for the truth, and she was someone I could identify with in her conversion from a personal loss of faith. Stein’s life reminds me that greatness demands more than easy answers.

Months into reading, I visited the Holocaust Museum in Washington, D.C. While I was in the museum bookstore, I struggled with one question that had come with me: Could I face the physical reality of Stein’s death as well as the deaths of millions of Jews? In order to have a better understanding of her life, I knew I had to face her death and the reality of the unfathomable suffering of all the victims.

The answer slowly formed in my mind, “I have come so far, I can’t quit now.” So with one cautious step in front of another, I walked out of the bookstore into the sacred space of the museum.

“If I cannot share the lot of my brothers and sisters, my life, in a certain sense, is destroyed.”

—St. Edith Stein

Stein was well aware of her place in Nazi society, yet even more certain of her Christian commitment: “Why should I be spared? Is it not right [that] I should gain no advantage from my baptism? If I cannot share the lot of my brothers and sisters, my life, in a certain sense, is destroyed,” she said at the end of her life. Then as she left the convent to begin her journey to Auschwitz, she would remark to her sister, “Come, let us go for our people.”

Stein embraced solidarity: “It is our vocation to stand before God for all.” Stein was willing to embrace the darkness of evil for the common good. She befriended that darkness in her compassion for everyone who suffered, for those who were indifferent, as well as for the victimizers.

It is her solidarity with all humanity that ultimately makes her my sister, as well as a sister to someone of any faith or even no faith. That was the focus of her prayer during her lifetime. That is her prayer for all of us now.

This article also appears in the May 2011 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 76, No. 5, pages 47-48). Click here to subscribe to the magazine.

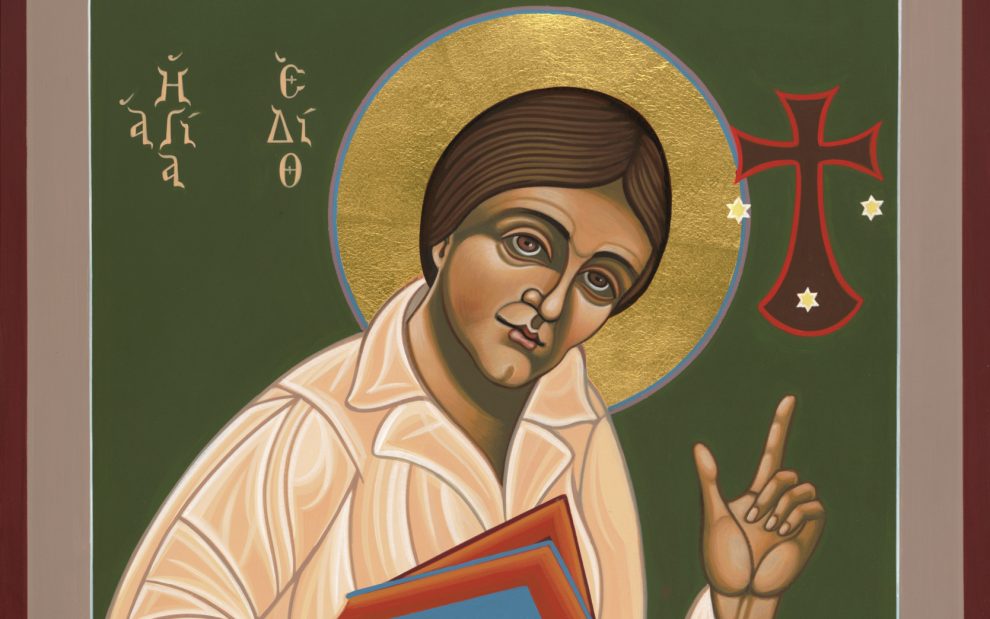

Image: Father William Hart McNichols

Add comment