What if cinema can kindle our hermeneutical impulse so that we are able to imagine women disciples gathered around Jesus’ table, and walking shoulder to shoulder with men in Jesus’ active ministry life? While a number of titles of the Jesus-Film genre conform to the androcentric view of a favored male discipleship, a few have birthed thought-provoking imagery that portray women not simply as adjunct, behind-the-scenes characters, but as visible and involved disciples who stand on the truth of who they are—bearers of a fuller, authentic humanity.

Godspell (dir. David Greene, USA, 1973), the film version of the eponymous Broadway musical on the life of Jesus re-set in contemporary New York City, challenges biblical conventions in its anachronistic re-contextualization of the gospel of Matthew in the hippie culture of the 60s and 70s. Jesus, an emblematic, counter-cultural clown figure, recruits a multi-racial group of ordinary working people to join his ragtag team.

Instead of twelve, he only summons nine to his inner circle of apostles, but what is truly novel is that five out of the nine are women. Outnumbering the men, women disciples in the film occupy a prominent place at Jesus’ table, and serve as co-equal partners at every stage of his saving ministry.

Controversial when it was released for speculatively exploring, under licentia vatum or poetic license, aspects of the human nature of the historical Jesus that the gospels are silent about, The Last Temptation of Christ (dir. Martin Scorsese, USA, 1988) contributes to a more inclusive view of women in its imaginative last supper scene. Set in an undisclosed locale abuzz with ritual and activity, Jesus’ Passover meal is seen first from a top view—the disciples are gathered around Jesus in a horseshoe sitting arrangement.

As bread is broken and passed on from one disciple to another, the camera offers a closer view that reveals the presence of three women disciples sharing the meal; Mary Magdalene, and the sisters Martha and Mary, are seated alongside the male disciples. A notable departure from traditional, gender-biased representations, The Last Temptation of Christ depicts the women disciples as partakers of Jesus’ meal, not invisible servants relegated to performing kitchen chores.

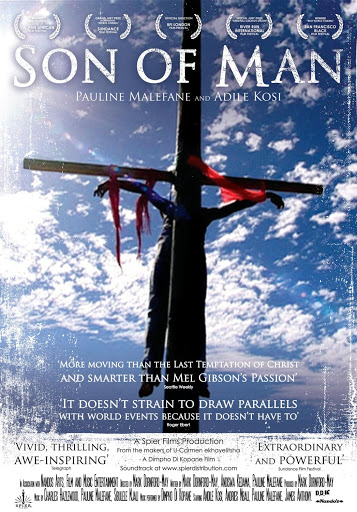

A truly compelling representation of women disciples is clearly seen in Son of Man (dir. Mark Dornford-May, South Africa, 2006), a critically acclaimed film that boldly inculturates the gospel story in an undisclosed, contemporary African context reeling in the turbulence of internecine war and abusive military rule. In a township identified only by the symbolic name “Judea,” a black African Jesus emerges as wisdom figure and prophetic mouthpiece, denouncing corruption and violence while trumpeting social transformation and the shalom of God.

An early scene is of interest; Jesus calls ordinary people to follow him, and in stylized manner, each of their names is spelled out across the screen in bold letters. The first set of disciples are predictably male, until Jesus calls three individuals whose male names literally and visibly change to female—Simon (the Zealot) becomes “Simone,” Philip becomes “Philippa,” and Thaddaeus becomes “Thaddea.” The sequence not only promotes the inclusion of three female disciples, it does so in a deliberate manner that highlights the significance of the “correction,” thus, elevating it to an ethical imperative.

In the film’s dramatic arc, the women disciples participate in Jesus’ ministry as disciples who are integral to the unfolding of Jesus’ mission. Referring again to the last supper scene, a rustic “Third World” rendering where Jesus and the disciples share a drink in common from an aluminum pail, the women are not huddled together in some reserved token niche but are interspersed among the men. It is noteworthy that Philippa occupies a privileged place; she is seated immediately next to Jesus on his left hand. Widening the aperture, the film’s portrayal of Mary solidifies not just the inclusion, but the primacy of women disciples in Jesus’ ministry. Here, the mother of Jesus is depicted as an inculturated African embodiment of the “Mary of the Magnificat” found in Luke 1:46-55, literally singing her prophetic-liberating canticle full-voiced in the middle of her pregnancy amid the crossfire of male-dominated firepower.

Later in the film, when the military attempts to disrupt the gathering of disciples at the foot of the cross, the male disciples recoil in fear, and it is Mary and the women disciples who frontline a defiant ritual song-and-dance to denounce and protest the politicized intrusion of the armed soldiers. The film suggests, in more ways than one, that Mary, the mother of Jesus, is the model of discipleship par excellence, an image that meaningfully resonates with feminist theologies and the Second Vatican Council.

Like new stained-glass windows, Jesus-films may contribute to the expansion of the field of imagination as they invite a mutually enriching intertextual dialogue with the gospels, most especially with Luke, which includes more episodes featuring women than any other Gospel, as ambiguous as their portrait may be. The creative crossing between the cinematic and the biblical challenges established kyriarchical hierarchies, even as it offers a transformative vision of a church that truly embodies a discipleship of equals.

The essay was originally published in Wisdom Commentary: Luke 10-24, vol. 43b, eds. Barbara E. Reid, OP, and Shelly Matthews. Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press, 2021, 584-585.

Image: An African image of “Mary of the Magnificat” in Son of Man (© 2006 Spier Films/Lorber Films)

Add comment