My colleague Jane and I met over Zoom with a congregational leader in Brooklyn, New York a few months into the COVID-19 pandemic. Tears flowed as the woman shared stories of parishioners moving away from the city, being unable to host the programs they’d planned, and wondering what the congregation would look like post-pandemic. Heaviness lingered across the ether.

After a moment, Jane sighed and said gently, “It sounds like your congregation is experiencing deep vocational grief.”

Jane’s suggestion did not make the pandemic pains any easier to stomach, but it did offer a framework for thinking theologically about the situation. Vocational grief refers to the emotions and losses people experience when significant callings in their lives become difficult, burdensome, or lost.

Vocational grief refers to the emotions and losses people experience when significant callings in their lives become difficult, burdensome, or lost.

For many Catholics, the words vocation and calling conjure up images of priests in collars or women religious in full habits. However, a more expansive theology of vocation recognizes that God calls people in all walks of life in myriad ways.

Kathleen Cahalan, director of the Called to Lives of Meaning and Purpose Initiative at the Collegeville Institute in Minnesota, uses prepositions to explore different dimensions of calling. She writes, “Vocation entails being called by God, to follow, as I am, from loss, for service, in suffering, through others, and within God.”

Cahalan points to the dynamic nature of callings, which are multiple and can change over time. Sometimes vocational transitions spark joy, like becoming a grandparent or accepting a dream job. At other times, changes in callings carry grief—a reality known by far too many during the COVID-19 pandemic.

For some people, their vocations became difficult or burdensome over the past year. Consider the student struggling with virtual school, the nurse working exhausting hours, and the single person sitting all alone in isolation.

Other people have lost the ability to live out a calling. Think of the waitress whose restaurant closed, the usher whose church worships online, and the daughter whose parents died after contracting the novel coronavirus.

I asked dozens of people about their vocational grief during the COVID-19 pandemic. Everyone, without fail, had something to share. Below are stories from six people at different stages of life during the pandemic.

So much has been lost these days. Let us cling to the callings that remain: to pray, to listen, to tell stories, to assure one another that in times of grief we are never alone.

A parent’s calling

Stina Kielsmeier-Cook and her two young kids scrambled into their local Minnesota library last spring with an urgency usually reserved for chasing down the last bus. “How else will we entertain these children?” Kielsmeier-Cook worried as they carted out 150—yes, 150—books to the car. Schools, libraries, and other places of refuge for parents were beginning to shut down. Normalcy had left the station. Next stop: Who knows.

“I felt a tightness in my throat and worried I was getting sick,” Kielsmeier-Cook says of those early pandemic days. Her husband softly offered: “Stina, I think that’s anxiety.”

Overnight the two parents—and millions of others like them—found themselves juggling full-time jobs and ever changing child care needs for their third grader and preschooler. Already busy mornings now involved tasks like tracking down Zoom codes for virtual kindergarten.

“From one week to the next, we didn’t know: Is school going to be hybrid or back in person? How serious is COVID-19 for kids? Am I a bad parent if I’m putting them in child care?” Kielsmeier-Cook says.

Her multiple callings kept bumping into each other: to mother, to write, to work for a nonprofit. With only so many hours in a day, Kielsmeier-Cook—who launched her spiritual memoir Blessed Are the Nones (InterVarsity Press) during the pandemic—felt constantly stretched.

“I was trying to figure out how to meet my kids’ social, emotional, and spiritual needs while I struggled to keep up with my own vocational work outside of the home,” she says. “We were not created to do all of this alone.”

Kielsmeier-Cook soon realized she needed to prioritize personal reflection time or risk being consumed by grief. For her, this meant taking distanced walks with friends and carving out even two quiet minutes to check in with her spirit.

“I can’t take care of anyone else if I’m not in a healthy place as an individual,” she says.

REFLECT:

What is one small gift you can give yourself this week as you juggle multiple callings and many needs?

PRAY: Coronatide prayer for parents

Gracious God, ease the burdens of parents caring for their children during these isolating pandemic days. Give them rest and remind them of your saving love. Amen.

A pastor’s calling

The Rev. Cody Maynus had dreamed of his ordination since kindergarten: a church packed with his favorite faces, a festive dinner, and a night of dancing to celebrate this big vocational milestone. The reality of his June 2020 ordination was a stark contrast: Most loved ones logged on to Facebook Live while 10 masked people sat scattered around the sanctuary.

“We couldn’t even have lunch after,” he says.

The pandemic altered significant vocational rituals for many people. Weddings, graduations, ordinations, and the like were significantly pared down, postponed, or even canceled. Now people like Maynus, the rector of St. Andrew’s Episcopal Church in Rapid City, South Dakota, are left to navigate their next steps in an ever changing environment.

“The stuff of parish priesthood that called to me most, like being in the community with people, has been the least present part of my priesthood this year,” says Maynus. “In some ways I feel like the hunchback of Notre Dame, just sort of shuffling around the shadow of the church building while the city outside seems to be alive.”

Maynus spends much of his time tending to administrative matters like Zoom worship and building maintenance.

“I learned quickly that if bathrooms aren’t being used in a building regularly, the pipes can freeze and bust—the things they don’t teach you in seminary,” he says.

Pandemic restrictions prevented him from accompanying parishioners in person when pastoral needs did arise.

“Early on, a parishioner was dying,” he says. “I couldn’t anoint him or hold his hand. I couldn’t hug his wife. I couldn’t even bury him and commend his soul to God. All the things I feel called to do, I couldn’t do.”

Still, all was not lost for Maynus in his first year of ordained priesthood. He was able to represent his congregation at Black Lives Matter protests while masked and physically distanced. He also celebrated some liturgies outside and in creative virtual spaces.

“In some ways it feels like stepping into the missionary character of our diocese,” he says. “No matter where you are, you can have church.”

REFLECT:

How are you ritualizing significant vocational moments during the pandemic?

PRAY: Coronatide prayer for pastors

Gracious God, envelop pastoral leaders with strength during these difficult pandemic days. Grant them energy—and rest—as they journey with your people. Amen.

A writer’s calling

Vanesa Zuleta Goldberg cherishes her morning rituals: biking, letting the dogs out, praying a novena to St. Joseph. Afterward, each day looks different for the Texas-based freelance writer and content creator. “But it all happens on my dining room table!” she laughs.

A few months into the pandemic, Zuleta Goldberg transitioned away from her job as a diocesan director of youth ministry. As a Latina, she felt called to use her voice to respond to racism within the Catholic Church. She struggled to find time to do the necessary research and writing on top of a full-time job.

“I wanted to be in a space where I could engage with fellow Catholics and others on the realities of racism and ways we can be people rooted in justice and committed to breaking down cycles of oppression,” she says.

Many people have found their professional vocations disrupted during the pandemic. Some, such as Zuleta Goldberg, discovered a more urgent calling to pursue during the time in lockdown. Others did not have a choice. The COVID-19 pandemic ushered in a wave of layoffs, hour reductions, and other unwelcomed shifts in employment status.

Zuleta Goldberg and her husband carefully discerned the risks of leaving a full-time job during the pandemic. The couple is now down to one steady income. A hiring freeze blanketed her area of Texas at the time of her transition—which coincided with a peak in community infections—so finding additional work was unlikely.

“The COVID-19 pandemic opened my eyes to the ways we prioritize our finances,” she says. “We had to do strict budgeting when I left [my job].”

Zuleta Goldberg saves a few dollars by not writing from the coffee shop but misses being around people. Typing away alone in her apartment gets lonely. She combats the isolation by taking breaks during the day to connect with loved ones.

“Having an intentional plan for the day helps with the grief,” Zuleta Goldberg says. “I can look forward to calling my mom or FaceTiming my best friend while I eat lunch.”

REFLECT:

What was a major point of discernment for you during the pandemic?

PRAY: Coronatide prayer for writers

Creative God, inspire the spirits of writers and all who tell stories of this time. Sustain their work, that they may continue sharing your goodness with the world. Amen.

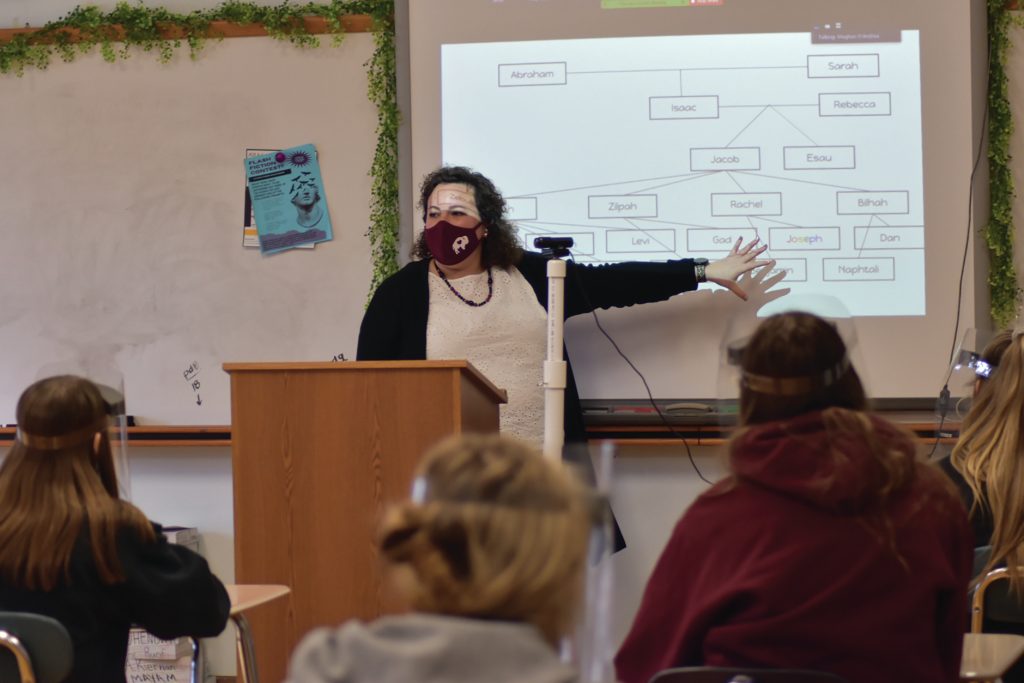

A teacher’s calling

Panic rushed through Meghan D’Andrea’s body as she stood in front of 110 first-year students on orientation day. The high school teacher, who became deaf in her late 20s, relies on reading lips and cochlear implants to communicate.

She could not make out a word muttered behind her students’ masks.

“My disability has always come second,” says D’Andrea, who teaches ninth-grade religion at Buffalo Academy of the Sacred Heart in Buffalo, New York. “I’m Miss D’Andrea, a teacher who is deaf. But this year, I became a deaf teacher, Miss D’Andrea. I’m so grateful that despite my illness and disability, I’ve always been in control. The pandemic has taken that control from me.”

She says, “My favorite parts of teaching are the in-between moments, the friendly chatter before class and banter in the hallways. Now I find myself shying away from interactions that require hearing. I feel bad for my girls, that they are stuck with me in the midst of this confidence crisis. I wonder if they are grieving the loss of a fun teacher too.”

The school eventually got clear face shields for D’Andrea’s students. Yet accessibility problems persist, leaving her haunted by painful vocational questions.

“I began to weigh my need for access—is my ability to discuss this answer with my students worth the risk of them taking off the mask?” she says. “What began as questions about the worth of information quickly transformed into questions about my own worth. Was I worthy to still be a teacher? Was I really the best thing for these kids? For my school? Somedays, I’m still not sure how to answer those questions.”

Accessibility is a crucial component of vocational support. When D’Andrea does not have to worry as much about basic communication, she’s able to live more fully her calling to teach.

“I have definitely become more organized and deliberate in my teaching this year,” she says. “Some of the old, tired lesson plans just don’t cut it when managing kids at home, kids in the classroom, and the looming threat of a shutdown.”

REFLECT:

What vocational questions is the pandemic raising in you?

PRAY: Coronatide prayer for teachers

Christ Jesus, support teachers toiling in the vineyards of education. Give them a glimpse of success in their students, no matter how small, so that they might be encouraged by the fruits of their labors. Amen.

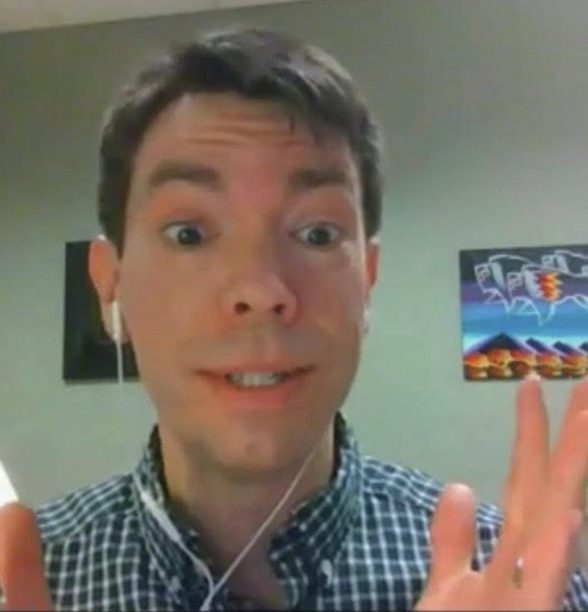

A campus minister’s calling

Steve Blaha cozies up and heads to his basement-turned-office. The veteran campus minister never imagined adding a blanket to his professional wardrobe. “But that’s ‘Quarantine: Campus Ministry Edition’ for you!” Blaha says.

The pandemic has thrown people in ministry many curveballs—gatherings cancelled, events moved online, people on high alert. Yet Blaha, who serves as assistant director of campus ministry at Marquette University in Milwaukee, senses continuity in the core of his calling

“The thread that continues is: How do I as a member of the baptized keep loving others? Who are the particular people in front of me who are hungry for God, and how do I best accompany them?” he says.

Those particular people are mostly young adults, many of whom face growing vocational concerns as the pandemic rages on: Will there be a job for me after graduation? When will I see my family again? An optimist at heart, Blaha notices the gifts arising from grief.

“People’s anxieties are increasing,” he says. “With that, there’s been a gentleness in movement, an openness of heart, a genuine holding of one another’s experiences, and a more robust desire just to be together.”

Blaha finds he is tapping into his creativity even more during the pandemic. For instance, he and a colleague started a morning show on Facebook Live to connect with students who are now more dispersed.

“We wanted to offer another space where students can share stories about how they are experiencing God and what their spiritual journeys look like in their lives as a form of encouragement to each other,” he says. “Social media is a real place—and the church is already there.”

REFLECT:

Are you experiencing any new areas of creativity in your callings during the pandemic?

PRAY: Coronatide prayer for campus ministers

Holy Spirit, stoke the callings of campus ministers who are accompanying young people during these anxiety-filled times. Spark their creativity, and kindle their well-being so that they may continue to do your good work in the world. Amen.

A retiree’s calling

My dad, Bill Bazan, leans back into his recliner—a familiar position these days. The 77-year-old does not venture out much during the pandemic. Like many older people, Bazan’s life slowed down immensely when COVID-19 hit in March 2020.

“Now, getting the mail is one of the highlights of my day!” says the Wisconsin resident.

Bazan spends these quieter days reflecting on how his callings have evolved over the decades, particularly his call to social justice ministry. He advocated for health care for the uninsured during his professional career. Now in retirement, he serves his community as a crossing guard at the local grade school. Before the pandemic hit, he spent three or four nights a week greeting guests coming into Saint Ben’s central city meal program.

Of all the callings altered by the pandemic, he misses serving at Saint Ben’s the most.

“Absolutely every day in my quiet time I think of all the wonderful people who came in for a meal,” he says. “I used to be there to welcome them, to give them a smile and fist bump. When I hold my life still, I can still see their faces.”

Bazan understands his callings to be deeply intertwined with the people around him, particularly those on the margins.

“People experiencing homelessness—Jan, Alex, and dozens of others—became my community and my teachers,” he says. “It wasn’t so much about what I was doing for them, but what they enabled me to do with them.”

He says, “The people at Saint Ben’s were instrumental in allowing me to be part of a larger community of people, which is important. I don’t think we’re ever saved alone. No one gets to heaven by themselves. We are saved with others, with our communities.”

For now, Bazan connects with his community through daily prayer and hopes that Saint Ben’s can open safely again someday. Hope, he says, is a crucial vocational practice.

“It can be tempting for older people to be more connected to the past than the future,” he says. “But there is still life in front of us.”

REFLECT:

What do you hope for in the days ahead?

PRAY: Coronatide prayer for older people

Spirit of Life, sustain the hope of those who are lonely and isolated during the pandemic, particularly older adults. Grant them community, care, and a renewed sense of your purpose for their lives. Amen.

This article also appears in the June 2021 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 86, No. 6, pages 26-30). Click here to subscribe to the magazine.

Image: Unsplash/David Veksler

Add comment