Though raised as an evangelical Protestant, I was first drawn to Catholicism when I encountered St. Augustine in an undergraduate philosophy course. Once I discovered modern Catholic social thought I was hooked. The beauty of this faith tradition, I found, lay in the authenticity of its view of human nature—the way faith and reason collaboratively inform a conception of human persons as intellectual, emotional, volitional, and, above all, relational. The principles of justice this view inspires capture the reality and hope of human existence.

My spiritual conversion, however, meant the dismantling of any political loyalties I held—Catholic faith frames a vision of political reality that is not easily adapted to either mainstream party in the United States. While Catholicism’s distinctive approach to human relationships—including politics—is what captured my moral imagination, it does make faithful political engagement a challenge.

The political divide that bifurcates our nation has rent the church as well. American Catholics reflect the broader population when it comes to political affiliation and are split nearly equally between Democrats and Republicans.

Our positions on economic and social issues, too, are not significantly distinct from those of our respective parties. For example, 80 percent of Democrats accept the strong consensus of climate scientists that Earth’s climate is warming due to human activity, while only 20 percent of Republicans do so—this is true for Catholics and non-Catholics alike.

Likewise, nearly 65 percent of Catholic Democrats think abortion should be legal in all or most cases. While this is lower than the 76 percent of Democrats, writ large, it is far greater than the 39 percent of Catholic Republicans who agree. These positions hold despite the fact that care for creation and special concern for the dignity of the unborn are both emphasized in the principles of Catholic social teaching.

The political divide that bifurcates our nation has rent the church as well.

Though Catholic teaching transcends political affiliation, Catholics often toe the party line rather than challenge those aspects of their party’s agenda that are incompatible with faith principles.

According to Centesimus Annus Pro Pontiface (CAPP-USA), Catholic social teaching “is built on three foundational principles—Human Dignity, Solidarity and Subsidiarity. Human Dignity, embodied in a correct understanding of the human person, is the greatest. The others flow from it. Good governments and good economic systems find ways of fostering the three principles.”

The Catholic tradition recognizes the unique dynamism of every person as created in the image of the triune God—inherently dignified and fundamentally relational—and it embraces the dependency by which we creatures are constituted. A robust political vision will attend to this.

The trinitarian roots of the Catholic principle of human dignity demand both personal responsibility and creative relational engagement, though the priorities of our political parties tend to reflect one or the other. Catholic social teaching offers a way forward, navigating the political divide by affirming some of the core convictions that motivate political action from both sides—subsidiarity and personal virtue, on the one hand, solidarity on the other.

Subsidiarity promotes responsibility: The primary responsibility of governments should be to facilitate the conditions that enable individuals, families, and communities to make their own decisions and address their own needs and to participate in the political process—larger bodies of government never should usurp the responsibility of smaller units but should lend support when smaller bodies require assistance.

Subsidiarity, Pope Benedict XVI says, “fosters freedom and participation through assumption of responsibility.” This freedom, however, is enriched by solidarity, which emphasizes that people are responsible for one another.

Solidarity affirms our relational identity by maintaining that our own flourishing is bound up with that of our neighbors. Indeed, Pope Paul VI makes the radical claim that solidarity requires those who are more privileged to “renounce some of their rights so as to place their goods more generously at the service of others.”

Rather than promoting one of these principles to the exclusion of the other, our policy positions should integrate a commitment to individual responsibility while recognizing that government intervention is an important tool for addressing systemic injustices.

Our policy positions should integrate a commitment to individual responsibility while recognizing that government intervention is an important tool for addressing systemic injustices.

For example, we need to reckon with the fact that contemporary evidence, as reported by the Hamilton Project, “shows that decentralized fiscal federalism—which provides for state and local autonomy—can disproportionately harm blacks and other non-white groups” and develop new approaches to lifting up marginalized communities while empowering them to determine and work toward their own good.

Solidarity should enrich subsidiarity, and subsidiarity should direct solidarity.

Unfortunately, our respective political parties—and the Catholics who profess loyalty to them—tend to divorce these interconnected principles, contributing to an ethic of individualism that cannot succeed in fostering just political activity.

The right tends to prioritize subsidiarity, which can lead to tunnel vision concerning individual virtue and self-reliance and an over-zealous commitment to a negative conception of freedom—freedom from external coercion or communal responsibility.

Such a view fails to capture the fundamental relationality of human beings and the reality that people exist within the context of their social systems. Indeed, subsidiarity is only conducive to individual flourishing if each individual is able to participate freely and fully in society.

The left, on the other hand, often promotes solidarity through a positive notion of liberty—freedom to participate fully in political and social life, facilitated by, as the editors of the New York Times put it, the assurance of “economic security and equality of opportunity.”

This view more readily invites government intervention over personal initiative, and the solidarity proposed here can be superficial if it does not recognize that individual responsibility and freedom from government overreach are critical to human flourishing.

Though our policy approaches might differ, those who follow Catholic social teaching should share the common goal to promote subsidiarity in solidarity in the service of human dignity.

We see the bifurcation of these principles in partisan reactions to our pandemic response. “The cure can’t be worse than the disease” is the emphatic refrain from one end of the political spectrum, unconcerned that systemic injustices make marginalized communities more likely to be sacrificed on the altar of the “greater good.”

This is met with the equally vigorous reply that concern for the economy should not trump concern for human life, but this ignores the unfortunate paradox that those most susceptible to COVID-19 related illness and death are those who are also most likely to lose their jobs and most vulnerable to economic crises due to systemic inequalities in income and health care. A just recovery will involve reordering the social systems that have fostered this dilemma.

Though our policy approaches might differ, those who follow Catholic social teaching should share the common goal to promote subsidiarity in solidarity in the service of human dignity. Our faith, rather than the consensus of our party, should inform our political positions. Both parties would benefit from the sympathetic criticism of their Catholic members.

The principles of Catholicism invite us to transcend the political divide and encourage faithful Catholics to advocate Catholic social teaching even—and especially—within their respective parties. Without this, Catholic witness will be disingenuous and incomplete.

Catholics have the opportunity to lead the way in the restoration of our nation, but we must commit to apply Catholic social teaching in all areas of our political engagement and to doing the work of listening and learning that this will require.

As we look toward the future, may this faith-based political vision take root in the consciousness of Catholics and animate a just recovery. If not now, when?

This is part one of a two-part series from Kathleen Bonnette on Catholic political vision. Read part two on racism and Catholic political vision here.

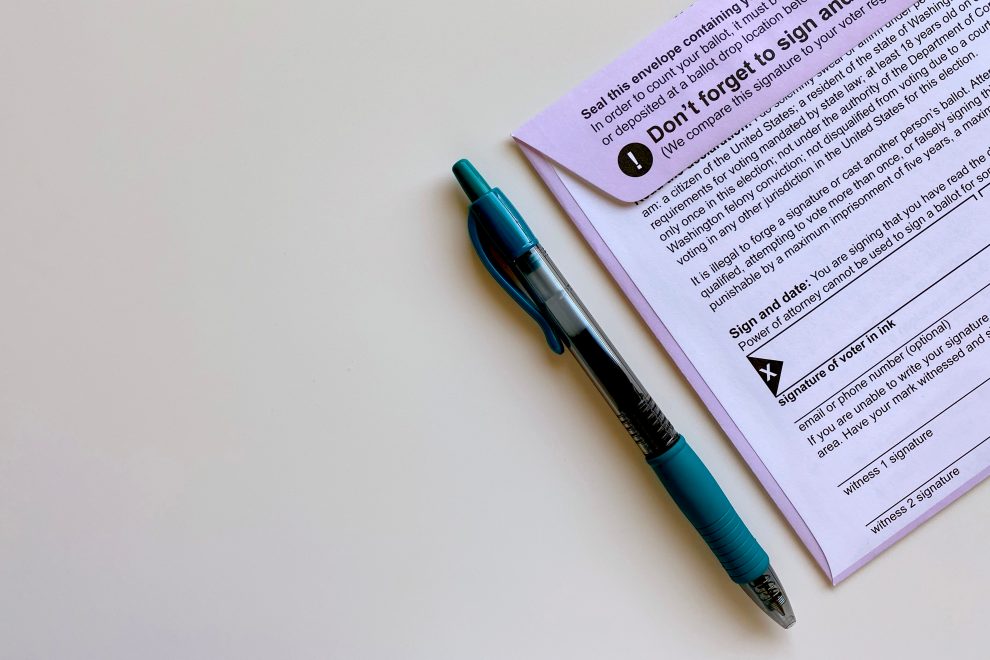

Image: Unsplash

Add comment