Our nation is engaged in a winner-take-all culture war. As Michael Grunwald says, this essentially entails “the transformation of even nonpartisan issues into mad-as-hell battles of the bases, which makes it virtually impossible for politicians to solve problems in a two-party system. Cooperation and compromise start to look like capitulation, or even treasonous collusion with the enemy.”

There are various historical and philosophical hypotheses that may explain how we got here, but at the heart of the current culture war lies a difference in the import each side confers to individual responsibility and systemic constructs. Responses to the racial tensions exacerbated by the murder of George Floyd—a Black man killed by police brutality—exemplify the divergence.

Though the injustice of Floyd’s death is not in dispute, there is disagreement concerning the existence and influence of systemic racism—social institutions structured to the benefit of white people and the disadvantage of people of color—which protesters say factored into Floyd’s death.

According to a Pew Research Center poll, 70 percent of Black Americans and 80 percent of Democrats believe that being Black in America “hurts a person’s ability to get ahead” and attribute this to systemic inequalities such as less access to good schools and high-paying jobs.

However, only 35 percent of white Republicans believe that being Black in America is an impediment to success. This subgroup is much more likely to attribute the challenges faced by Black people to individual or communal shortcomings such as family instability, lack of good role models, and lack of motivation to work hard rather than to systemic injustices.

Levels of support and disapproval for movements like Black Lives Matter thus fall predictably along party lines: Ninety-two percent of Democrats support Black Lives Matter, while only 28 percent of Republicans do so.

If the reordering of our social structures is to be empowering, not enabling, we must encourage the cultivation of personal virtue.

Further, according to a recent Morning Consult poll, a vast majority of Republicans view police violence against Black people as rare and think that isolated incidents—the “bad apples”—are sensationalized by the media. To the contrary, nearly 85 percent of Democrats agree that “police violence against black people is widespread and common, and we do not pay enough attention to systemic bias in criminal justice.”

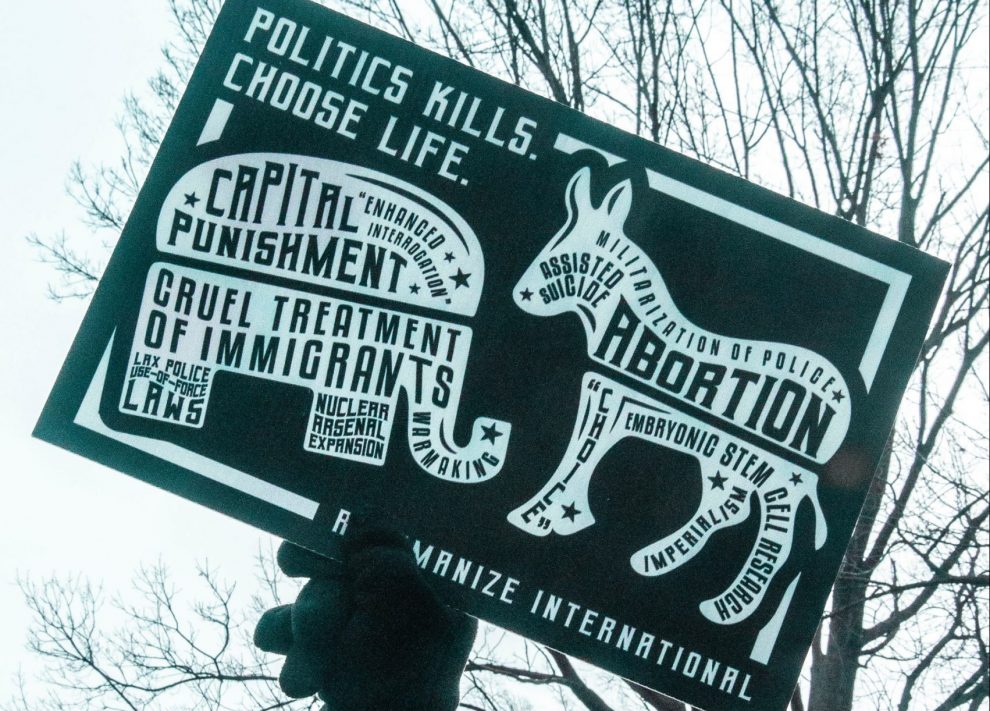

Unfortunately, Catholics are as politically polarized as the rest of the nation. Though the principles of Catholic social teaching cut across the political divide, Catholics typically profess positions according to party loyalty rather than church teaching. The current protests offer an urgent challenge to move beyond this political idolatry.

In a time when “culture-war politics are often a crutch, a look-at-the-shiny-ball distraction, an easy way to shift complicated policy debates from inconvenient facts to emotion and identity,” we will need a more robust framework for political activity than what is currently at work in our nation.

The paradigms of both the right and the left serve as important counterweights to each other, but independently both are impoverished. By promoting solidarity and subsidiarity in the service of human dignity, Catholics who faithfully apply Catholic social teaching can help develop just and creative responses to the social issues of our day that integrate the values espoused in both worldviews.

The right’s emphasis on personal virtue and self-reliance fails to capture our human reality as people made in the image of a trinitarian God—people who are totally and fundamentally relational. This individualistic view leaves little room for appreciating systemic injustices.

Despite ad hominem accusations to the contrary, most on the right do in fact condemn racism. Because they identify racism primarily as a personal vice, however, they conflate critiques of systemic racism with the vilification of individual persons—police officers, for example.

Insofar as explicitly racist worldviews are becoming more uncommon, charges that racism permeates the experience of Black Americans are easy to dismiss when one focuses solely on personal action.

There is ample evidence to suggest that virtues associated with social conservatism (such as chastity, perseverance, and temperance) contribute to a person’s socioeconomic success, though it is unpopular for progressives acknowledge this. The left’s prioritization of government intervention over personal responsibility can thus encourage dependency rather than flourishing.

If the reordering of our social structures is to be empowering, not enabling, we must encourage the cultivation of personal virtue. As Pope Francis warns, “Changing structures without generating new convictions and attitudes will only ensure that those same structures will become, sooner or later, corrupt, oppressive and ineffectual.” To deny this is to demean human dignity and to contribute to the destabilization of society.

St. Augustine recognized long ago that a virtuous citizenry is critical to national flourishing. In City of God, he argues that the human lust for power enslaves us with vices such as greed, insatiable ambition, and sensuality, which prevent us from developing just communities. In this, there is a critique of those on both sides of the battle lines.

The vices most likely to destabilize communities—pride and ambition in Augustine’s view—are celebrated “virtues” in contemporary America.

Advertisement

Those who identify personal virtue with success should recognize that the vices most likely to destabilize communities—pride and ambition in Augustine’s view—are celebrated “virtues” in contemporary America. Given the extremely disproportionate negative outcomes for people of color across all measures of socioeconomic factors, the individual virtue view perpetuates a negative bias toward people of color. It reinforces the belief that people who are marginalized or impoverished lack certain virtues or possess vices to a greater degree than those with wealth and power, though it is the virtues of American success that are the more worrisome vices. In our contemporary context, attitudes of moral superiority toward communities of color perpetuate the dominative forces of whiteness that play into the destabilization of American social fabric.

At the same time, those working to ensure social justice must attend to the cultivation of authentic virtue and personal responsibility or political engagement will become patronizing and ultimately misguided. We should heed the warnings of those such as Kay C. James, who warns of “misguided compassion” in welfare policy that “is destroying hopes and dreams [by] allowing despair-inducing welfare to take the place of pride-fueling work.”

The relativistic approach to morality perpetuated by those on the left will be self-defeating for any social justice cause. However, Augustine teaches that the virtue of humility is the key to justice: Without humility, those with privilege will always accuse rather than engage with those who are marginalized.

In the current political climate, humility is critical to developing policies that promote human dignity through solidarity and subsidiarity. In a survey by Third Way and Joint Center for Political and Economic Studies, the top priorities within the African American community include making housing affordable, lowering health care costs and providing universal health care, reducing racism, improving water and air quality, and improving access to education and higher paying jobs that make dual employment unnecessary. Stronger gun control laws, eliminating voting barriers, and reforming the criminal justice system also rank highly.

Without humility, those with privilege always will accuse rather than engage with those who are marginalized.

With an eye toward empowering people of color, we should join a commitment to individual responsibility with a recognition that social intervention is an important tool for addressing these systemic injustices. By hearing these concerns with humility, we can begin to move toward just and creative solutions.

Catholics are called to be peacemakers—to stand with the oppressed and to seek justice. Regardless of which political party we think will be most effective in facilitating flourishing, it is incumbent upon us to listen with humility to the voices of the marginalized and to put the values of our respective parties to work in finding solutions that meet their needs.

Culture-war politics should not define Catholic advocacy. We must act with the recognition that human nature is relational—that we cannot flourish independently of our neighbors, and that virtue and personal responsibility are not individualistic but should be ordered toward the common good. The principles of Catholicism invite us to transcend the political divide as we “act justly, love mercy, and walk humbly with [our] God” (Micah 6:8).

This is part two of a two-part series from Kathleen Bonnette on Catholic political vision. Read part one on political polarization, the pro-life movement, and Catholic political vision here.

Image: Unsplash

Add comment