The whole world had collapsed. Once he lived by the sea, embraced by ancient traditions in a thriving community of thousands. Now he was on the run in mountain wilderness, moving with his small band from one camp of grass huts to another, trying to stay ahead of the bounty hunters. He was always awake long into the night worrying about the children, knowing that at any moment the war dogs could descend upon them. When he did sleep, it was with two swords next to him.

But he also had Our Lady’s Sword. By day his rosary dangled from the side of the robe he wore over his armor. At night is when he prayed, holding on to the one solid anchor in the hurricane engulfing all the that he knew, sending up his voice to his Mother.

He prayed for protection from the war parties bent on destroying their world forever. Courage to face the possibility that it could all end at any time. And strength for something almost as difficult: fostering justice and harmony within the community, the authentic freedom of the fospel. That She Whose Heart Was Pierced by a Sword would intercede for him, he who was now a mother to his people in the Mother of All Lands.

This was the world and faith of Enriquillo, the undefeated Taino leader who led a successful 15-year rebellion on the island of Hispaniola in the wake of the most horrific demographic collapse the world has ever known.

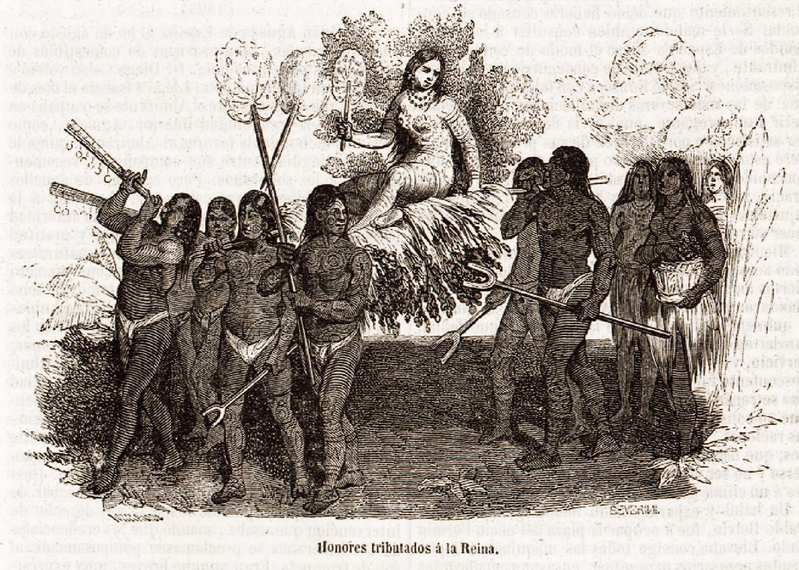

Enriquillo, or Guarocuya in his native Taino language, knew conquistador atrocities well. He was from the Kingdom of Xaragua, the southern half of what is now Haiti. He personally experienced and was permanently scarred by one of the most heinous acts in recorded history: In 1503, conquistadors invited Xaragauan leaders to a feast only to set fire to the meeting house and kill those trapped inside, including the 5-year old Enriquillo’s father. The conquistadors put a public exclamation point on the massacre by hanging Enriquillo’s aunt, the great Queen Anacaona, in Santo Domingo shortly thereafter.

This event was merely one act in a long tragedy: Over the course of a couple decades, the Spanish destroyed five cacicazgos, or Taino kingdoms, and murdered 100,000s. In 1514, 22 years after Columbus first set foot on Hispaniola, only 29,000 Taino remained, reduced to servitude.

In 1514, 22 years after Columbus first set foot on Hispaniola, only 29,000 Taino remained, reduced to servitude.

By 1519, Enrique could take no more. Now a Cacique, or headman, he and about 30 followers escaped to the Bahoruco Mountains in what is now the Dominican Republic. The pine-covered forests and desert scrub of this remote southern region hid their network of villages. They gathered wild plants, raised chickens with their tongues cut out, cultivated scattered cassava plots, and hunted the feral pigs that had taken over the island. Caves, like the ones the Taino said they originally emerged from and which were often decorated with petroglyphs, served as the group’s hideouts.

And the rebels began to win. They defeated the war parties sent to retrieve them. They hit the colony where it hurt and disrupted the gold trade. The community attracted other Taino refugees and African runaways, such as the rebel Tamayo and his followers from the other side of the island.

The village grew to include 300 rebels, and colonial authorities began to fear that Enriquillo’s new social order would take over the island. These battles are not like those in other parts of the Americas, a frustrated colonial official reported, “because here it is war with Indians educated and raised among us, and they know our forces and customs.”

Enriquillo utilized Spanish arms and, just as importantly, understood the double-speak and brutality of the conquistadors. Yet he rejected these tools. In place of torture, rape, and murder, Enriquillo practiced mercy.

When his band trapped a colonial war party of 72 people in a cave, instead of burning them out Enriquillo took their weapons and released them. His approach internalized just war theory at its best: Sometimes war may be the only option, but it must be done differently and with mercy. Enriquillo’s mercy even birthed a vocation: One freed soldier entered the Dominican friary as a result.

Enriquillo’s mercy on the battlefield was a reflection of his faith. Enriquillo was raised in a Franciscan friary after his father’s murder and had more deeply imbibed the Gospel than almost anyone on the island. Crosses adorned the huts of his hidden village. During peace negotiations, the rosary-saying Cacique requested a bell and religious images for the village’s church. And when Father Bartolomé de las Casas, the famous Dominican friar known as the Defender of the Indians, visited the rebel village, he spent a month baptizing babies and saying Mass.

In place of torture, rape, and murder, Enriquillo practiced mercy.

Enriquillo’s matter-of-fact faith belied the shallow conquistador claim that their pillaging was somehow a religious crusade. At their most candid, conquistadors admitted what Francisco Pizarro did when told by a priest he was there to evangelize the Indians: that “he had not come for any such reasons; he had come from Mexico to take away from them their gold.” Not so with Enriquillo and his faith.

Even today, the mountains of Quisqueya—“Mother of All Lands” in the Taino language—vibrate with a spiritual presence like nowhere else on Earth. You first feel the vacuum left by a lost world. Gradually, you learn that this “lost world” is still there, both in the life of descendants of the land’s original inhabitants and pulsing in the darkness at night.

The rebels felt this world. They told stories of the old days to the children and maybe sang some areítos, epic ceremonial songs that unified Taino lifeways and ways of knowing. And after the villagers fell asleep, one by one, Enriquillo would have sat awake murmuring Hail Marys while he communed with the spirits of the ancestors.

The colonial government could not defeat Enriquillo. They capitulated to his demands, and in 1534 he and an entourage of 20 men journeyed to Santo Domingo. Where Queen Anacaona had hanged 30 years before now, the whole town turned out to catch a glimpse of the unconquered Cacique Guarocuya, no doubt armed with Our Lady’s Sword at his side.

It is easy to project too much on revolutionary figures who don’t live to do the hard work of building a new society. Enriquillo may be the exception.

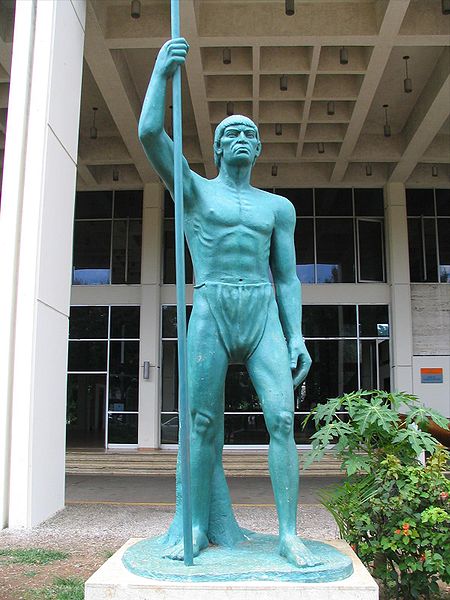

Though Enriquillo died only a year later, his spirit lives on. Monuments, such as the one dedicated in Azua in 2010, sprinkle the cities of the Dominican Republic. Haitian revolutionaries chose to name their new nation with the Taino name Ayiti (“flower of high land”) to harken back to the legacy of Enriquillo and the rest of the original inhabitants of the island.

Dominican sonero Victor Waill and La Orquesta Sabotaje captured this spirit of authentic freedom in their 1973 song “Enriquillo:” “You live forever in our memory . . . you won what you desired, that your brothers and sisters live in peace and love.”

It is easy to project too much on revolutionary figures who don’t live to do the hard work of building a new society. Enriquillo may be the exception. He had a 15-year track record of public faith and cultivating a social order imbued with the principles of what came to be known as Catholic social teaching. He is not a relic but a spiritual founding father who Haitians and Dominicans alike invoke as a new source of unifying power for an island scarred by too many tragedies to count. And a spiritual founding father for all North and South Americans as we work to overcome the lingering divisions born of conquest and slavery.

This year, get out your rosary to honor Enriquillo. September 27 is Día del Héroe de Bahoruco in the Dominican Republic. Pray the rosary and send up your voice with Enriquillo, champion of the rosary and authentic freedom, whose prayer still echoes in the Quisqueyan darkness.

Enriquillo, may you live forever in our memory, may we too win what you desired.

This article is also available to read in French and Spanish.

Image: Unsplash

Add comment