It started as a typical Sunday in the late 1960s as my family made our way to attend Mass at St. Leo’s Church in Milwaukee’s central city. But a single event would shatter our weekend and make an indelible impression on my 11-year-old mind. We arrived to discover that someone had spray-painted the face of the Mary statue on the church grounds to make it black.

This was an era of Black Power protest music, impassioned civil rights marches, dramatic conflicts over open housing and changing neighborhoods in light of white flight, and growing racial pride and awareness as my friends and relatives—indeed the whole community—struggled with whether to call ourselves “Negro,” “Afro-American,” or “Black.”

All of these social currents now became manifest in the church through the loud and difficult arguments that erupted in the parking lot. Was this an act of desecration, as some claimed, or an expression of racial pride? Was it a reclaiming of the parish in light of its racially changed neighborhood and membership or an act of disrespect to the remaining white parishioners who built the church and created its sacred decor?

What is the color of God? Of Jesus? Of Mary? How do we imagine the sacred and the holy? Such questions are freshly relevant as our nation wrestles yet again with its tragic history and continuing scandal of racial injustice. They also take on new urgency in light of a study in January out of Stanford University.

Researchers there examined how American Christians articulate their image of God. They arrived at a startling finding with significant social implications. They discovered that when people view God as a white man, they also are more likely to believe that white men are better suited for positions of leadership and authority than women or Black people. The chief researcher, psychologist Steven Roberts, summarized the major conclusion of his team’s studies: “Basically, if you believe that a white man rules the heavens, you are more likely to believe that white men should rule on Earth.”

This conclusion challenges the innocence of the sacred icons in the vast majority of Catholic churches. It gives empirical support for the criticisms of those who have long suspected that overwhelmingly white depictions of the sacred have dire social consequences. Malcolm X, for example, in his famed autobiography, avowed that exclusively white images of God, Jesus, and Mary perpetrate a “dual brainwashing,” convincing white people of their superiority and Black people of their inferiority—both being the will of God.

Feminist theologian Elizabeth Johnson wisely observes that how we conceive of God shows how we understand the greatest good and the highest beauty. If God and the sacred are presented mostly in white images, it is difficult to avoid concluding that those who most closely resemble those images reflect God’s goodness, beauty, power, and authority in a way that people of color do not—and cannot.

This is not a plea for “political correctness” in our church decor and religious textbooks. Something far more important is at stake. Predominantly white sacred images obscure and denigrate the sacredness of nonwhite lives and bodies. They instill in white people—and especially white men—a false sense of superiority.

Moreover, since God is beyond race and gender and historically Jesus and Mary were certainly not Nordic Europeans, constantly depicting these figures as white implicates the church in racist complicity—and religious idolatry.

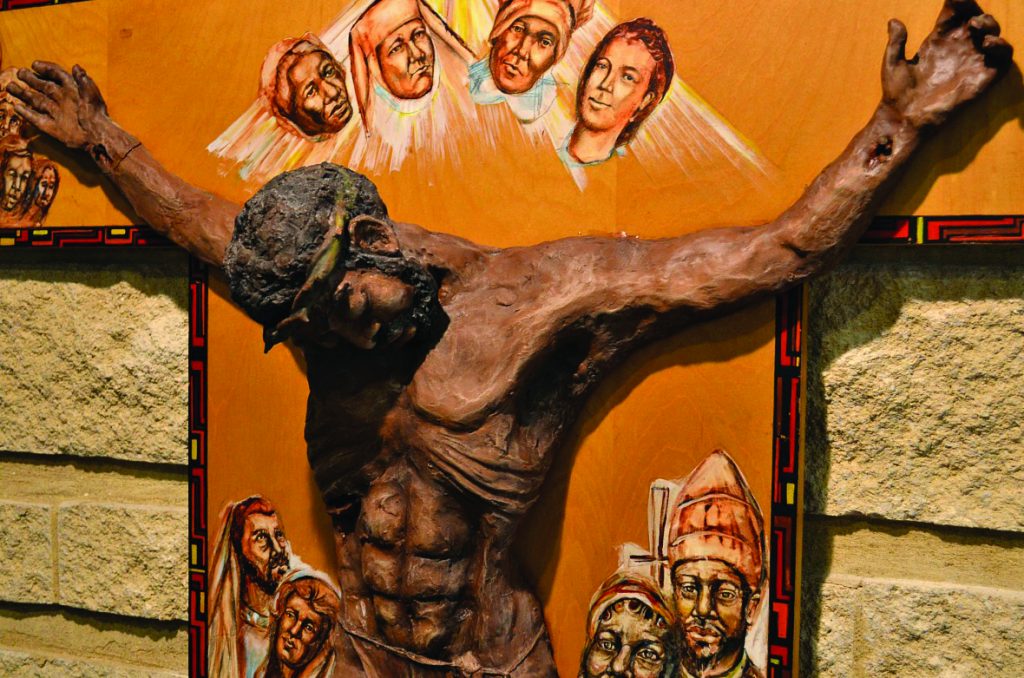

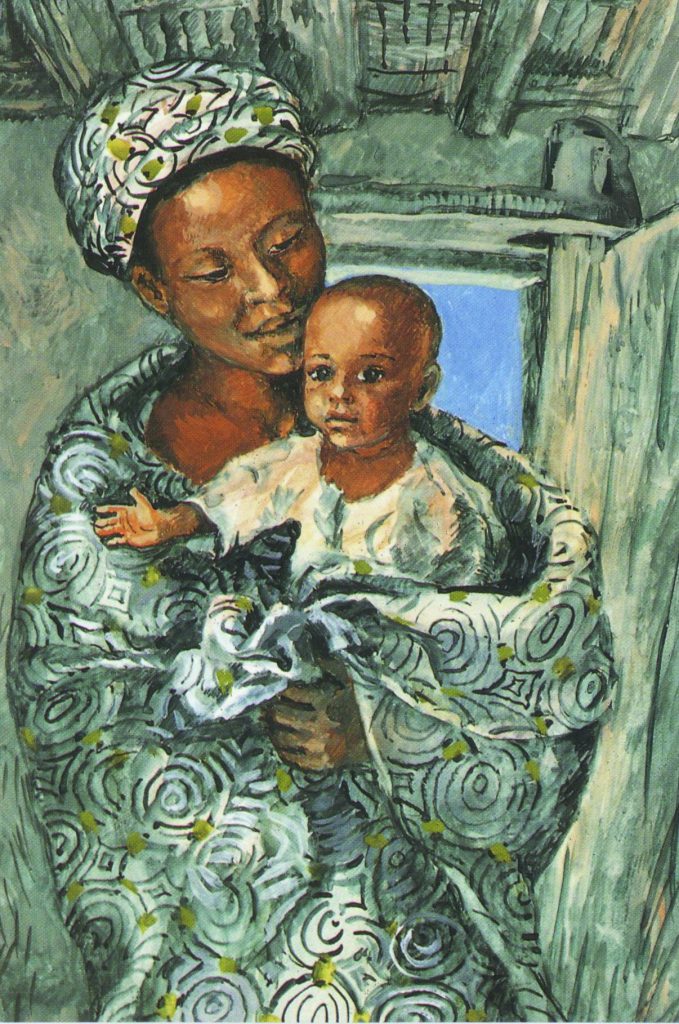

The arguments in my childhood church parking lot have long been resolved. In Black Catholic churches around the country, one finds statues and artwork that depict Black models of holiness and sanctity. Black people are seen in the image of God. But what of the rest of the nation’s parishes? Since God is beyond race and gender, then shouldn’t our sacred art better represent “on earth as it is in heaven”?

It’s time for some arguments and discernment in American church parking lots—and chancery offices and publishing houses.

This article also appears in the September issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 85, No. 9, pages 40-41). Click here to subscribe to the magazine.

Image: Scott Lorenzo, “Baptism of Jesus”

Add comment