The evening before I was to lead a day-long workshop on “Our Universal Call to Care for Creation,” I asked my parents if they would listen to my keynote presentation.

After 75 minutes of detailing Christianity’s inherent ecological consciousness and various approaches to living ecologically ethical lives, I asked if they had any questions. My mom, with more of a revelation than a query, said, “So that’s why you became so ‘green.’ It’s because of your faith.”

She was right. A deep dive into ecological theology, followed by fascination with Pope Francis’ encyclical Laudato Si’ (On Care for Our Common Home), taught me that sustainable lifestyle habits are required of Catholics if we intend to live lives that glorify God.

After limiting the use of fossil fuels, reducing dietary dependence on animal agriculture is the second most effective method of preventing climate change and environmental degradation. That means that eating less meat is a significant way to live out the Catholic call to care for creation—in terms of both tilling and keeping the Earth and caring for the Earth’s most vulnerable communities.

The notion that humans are called to care for the vulnerable among us is a foundation of Catholicism. How we do that looks different in different ages of history and stages of understanding. Today, excessive consumption of resources in one part of the world has lasting impacts on communities across the globe. As Pope Francis asserts several times in Laudato Si’, “Everything is connected.”

For example, animal agriculture requires 18 times more land use than what is needed to produce the same amount of food for someone who maintains a vegan diet. Often, large forests are cleared to create grazing space for animals. The deforestation results in increased carbon dioxide levels in the atmosphere, which affects weather patterns.

The cattle farmer responsible for clearing land may not be affected or may be able to adapt. But vulnerable communities around the world suffer, such as a fishing community in Bolivia that historically relied upon Lake Poopó for their catch. Climate change has caused the lake to disappear, along with the community’s livelihood. The people who once relied on Lake Poopó must now emigrate or learn an entirely new set of skills to survive.

It is good to address this community’s immediate needs now that they are hungry and without the means to sustain themselves, but it would be better to have implemented systemic changes that would have preserved the lake and its fish in the first place. This would have allowed the community to remain in their homeland and maintain their traditional livelihood. It would respect their dignity and work, a key component of Catholic social teaching.

Eating less beef decreases the demand and lessens the amount of land needed to graze a sufficiently sized herd, limiting these negative ecological effects.

Poultry, pork, and other animal agriculture products have similar effects on the global ecosystem. Pig farms are infamous for the egregious amount of animal waste they produce. Although some farmers attempt to contain the waste, it seeps into the earth and overflows into water systems, contaminating water sources for (usually) poor communities, who are more likely to live nearer run-off locations than their wealthier counterparts.

It is good to support clean water infrastructure and water purification measures so that public water can be used and consumed, but it is better to invest in systemic change that prevents contamination from ever happening.

Swooping in to deliver a superficial remedy to address a problem our own actions have knowingly caused is not care for the poor. It is exploitation of the vulnerable by those in positions of power and privilege.

Instead, Catholics are called to live in a way that supports just systems and abundant life across the globe, thus reducing the need for such altruistic aid.

When it comes to climate change and environmental devastation, our local actions truly have global reach.

The concept of adjusting one’s diet with religious motivations is not foreign to the Catholic faith, though typically these conversations revolve more around prayer, suffering, and solidarity than they do around tangible effects on life and justice causes.

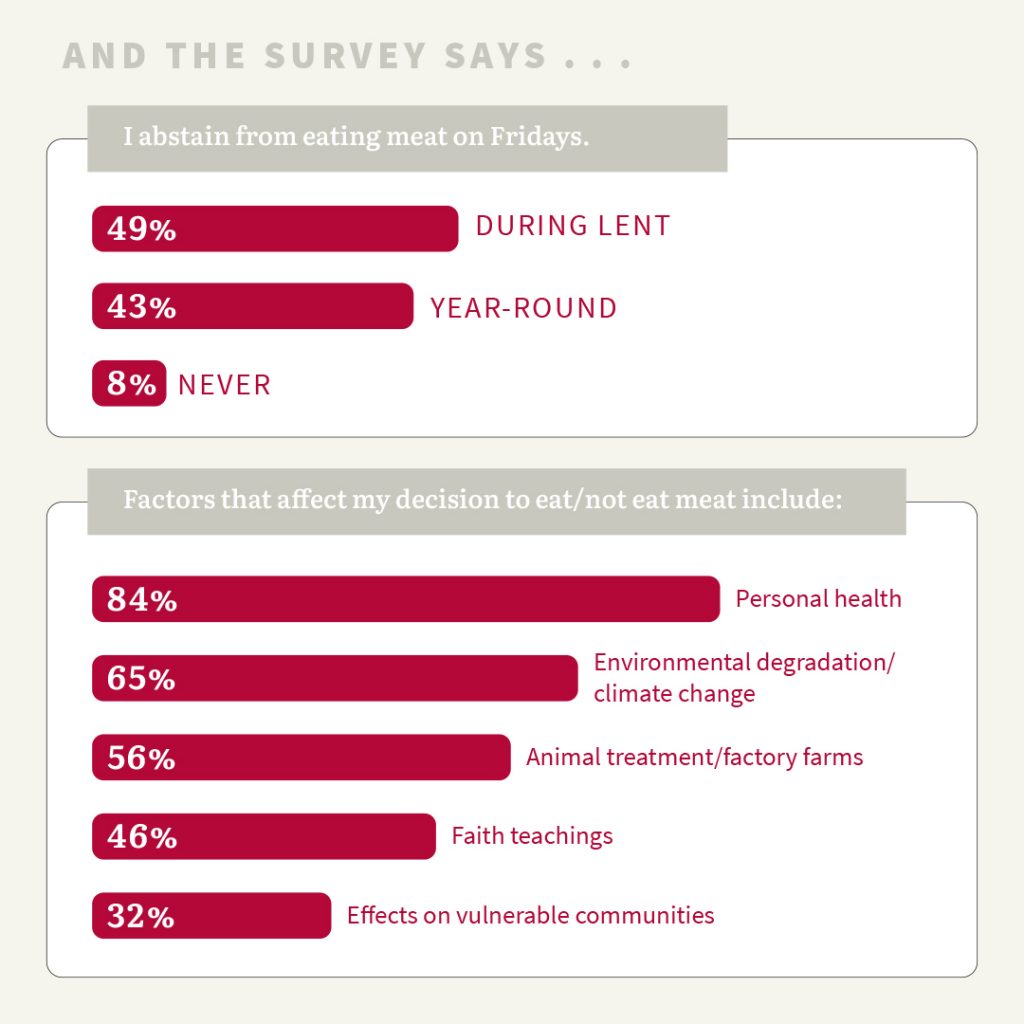

Each year during the Lenten season, Catholics practice an obligatory fast and abstain from meat on Fridays. Historically, this Friday fast was practiced year-round; some Catholics still voluntarily abstain from eating meat on all Fridays, which often is considered a pious and prayerful dedication to the faith.

Why then, if someone decides to abstain from eating meat every day, forever, is the validity of their faith commitment suddenly questioned? If it is spiritually beneficial to go without some of the time, then arguably it is even more beneficial to challenge oneself to go without at every meal, every day.

In fact, the benefits are beyond spiritual.

Abstaining from meat consumption, especially in the United States, takes discipline and consistency and requires paying attention to one’s own desires and the effect that meeting those desires will have on others.

Each time someone chooses to not eat meat—potentially three times a day for most people, once at every meal—they are choosing to recognize the interconnectedness of all that exists, to prioritize the well-being of the planet and its most vulnerable communities above their own appetite, and to more fully live out their Catholic calling to care more about justice for others than they do about comfort for themselves.

To support the argument that Catholics should eat less meat does not mean that every Catholic must adopt a strictly plant-based diet to achieve salvation. But it is reasonable to suggest that Catholics should strive to reduce their meat consumption to fewer than the three hamburgers per week consumed by the average American.

Some activists in the meat-free arena encourage what they call a reducetarian or flexitarian diet: a strategy for decreasing one’s meat consumption without removing it from the menu entirely. A reducetarian diet could mean following a pescatarian, vegetarian, or vegan diet most of the time, but allowing for meat consumption during holidays or when attending public events. This may sit well with those who find great value in feasts among the fast.

Someone looking for an even less stringent approach might experiment with abstaining from meat on all Fridays of the year in line with Catholic tradition or partaking in the secular movement for meatless Mondays, a movement introduced during World War I to conserve resources then made popular again in a 2003 public health campaign. Another approach could be to eat plant-based foods for breakfast and lunch while still including meat on your dinner plate.

There are many Catholic resources to aid in adjusting one’s meal plan for a more plant-based focus. The Sisters of Mercy promote Mercy Meatless Mondays during Lent and the Season of Creation (September 1 through October 4), though their guides for prayerfully living meat-free can be utilized year-round. Catholic Relief Services offers meat-free recipes from around the world as part of its annual Rice Bowl Lenten Program. Browse the dozens of options by year or country of origin for delicious new dinner ideas.

God gives humanity “every plant yielding seed that is upon the face of all the earth, and every tree with seed in its fruit . . . for food” (Genesis 1:29). To consume what is beyond this abundant gift is to imply that what God provides is not enough. For a truly Catholic diet, eat more plants.

This article also appears in the September issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 85, No. 9, page 31-34). Click here to subscribe to the magazine.

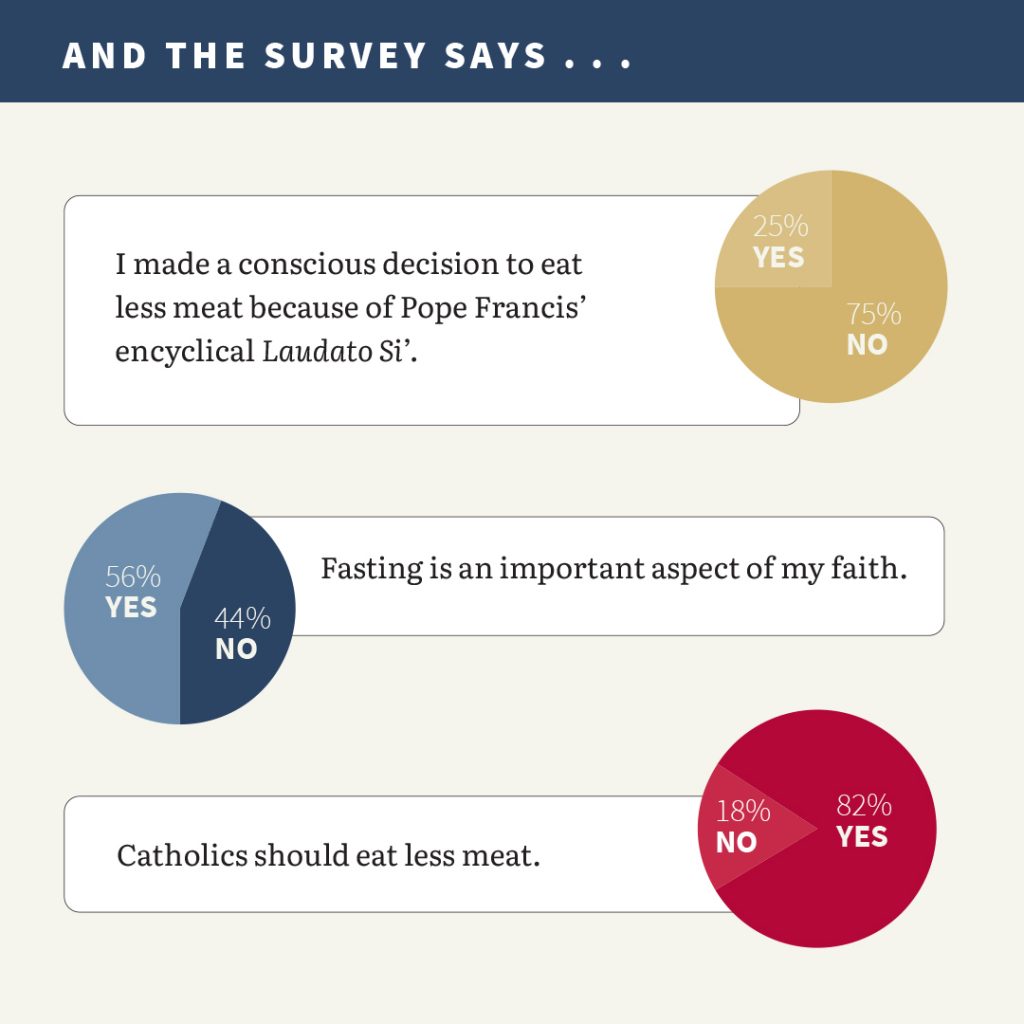

Results are based on survey responses from 163 USCatholic.org visitors. Sounding Board is one person’s take on a many-sided subject and does not necessarily reflect the opinions of U.S. Catholic, its editors, or the Claretians.

Image: Unsplash cc via Bannon Morrissy

Add comment