I pulled out a bright green Naugahyde chair from the pile in the sparse room and started down the checklist in my mind. Let’s see. . . . The two bathrooms were unlocked, one for the men, one for me. I had dragged the heavy oak podium across the room to place it near the table that would soon serve as an altar. The consecrated hosts were safe in a pyx in my black leather burse. I’d set up five chairs in a row in front of me and put missals on the seats. Everything was in place.

I grabbed my binder off the podium and began to study my reflection notes. As a new prison chaplain, I struggled each week to present a gospel reflection that would mean something to the men to whom I ministered. Many of the inmates in this institution are mentally challenged, and I wasn’t sure how well they could follow the readings and the reflection afterward.

Glancing at my notes, the story of the Good Samaritan and my reflection on God’s mercy seemed pretty straightforward. I had summed up the essence of what I wanted to convey in a single paragraph: If you’ve never been shown an ounce of mercy in your life but have let even a smidgen of God’s love into your heart, out of that smidgen of love you can begin to offer mercy to yourself. As you do that, God’s mercy will begin to flow out of you and into the others around you.

Did I even believe that myself? Fresh out of high school, after being raised Catholic, I’d left the church to marry a street evangelist who I believed would lead me into places with God I’d never been. However, while teaching me a lot about the God he thought he knew (a God as violent as he was), this man knew nothing about God’s mercy. I left that marriage 13 years later, broken and bruised, wondering if anything I had learned from my Catholic faith was even true. Desperately in need of God’s mercy, I sadly turned away from God and to alcohol for comfort.

That was many years ago. Then, just last year, the yearning for God arose inside of me so intensely—at times I could hardly breathe—that I eventually found the desire and courage to return to my childhood faith. Thanks to a perceptive spiritual director who knew how to direct comfort and encouragement at my wounded self, I began to learn that God’s mercy was something that had always been available to me, but that I was only beginning to understand how to access.

I had been teaching writing courses in jails and prisons for 25 years. Yet when hired by the archdiocese as a prison chaplain, I’d confessed to my supervisor, “I know so little of God.” Translation: I’m not worthy. My wise supervisor said, “You and the inmates will learn together.”

I glanced down at my notes once more. I knew it might be a bit too much to expect, but I so desperately wanted to bring the concept of God’s mercy to these men, particularly to one, Justin, so that he could rise above the ashes of his violent and abusive childhood. Now 35, he’d spent all but one year of his life locked up since he was 15. During his childhood and adolescence, his parents had beat him repeatedly. Even in prison his mother conveyed the message that everything that had ever happened to him was his fault as he was such a “difficult child.” My heart broke for him every time I arrived at the prison.

Soon the men arrived. I greeted them one by one with a handshake, sometimes holding on a moment, knowing that they don’t feel physical touch very often.

The communion service, still new to me, went well. The men here are gently teaching me. It is very humbling. They tell me when to sit down, when to stand up, what to say, what not to say. One time when I mentioned, “St. Leo the Great who served as pope in 450 B.C.—” Justin’s hand shot up.

“I don’t think so,” he said, not unkindly but quite confidently. “The Catholic Church originated with Jesus, and he wasn’t born yet. I think you mean 450 A.D.”

Of course. Duh. Justin always listened so closely to every word I spoke during the communion service.

After we said our last “Amen,” we gathered in a circle around a large table to pray, meditate, and discuss the reflection.

“Let’s take a look at our reflection questions, pick one, and try our best to answer from our hearts,” I told them.

I usually went first to get things going. I picked the third set of questions: Has anyone in my life shown me mercy? If so, what broke inside of me? If not, in spite of that, what will it take for me to cultivate a merciful heart toward others? I tried my best to answer as honestly as I could.

“I have been shown mercy. Many times, actually.” I was hesitant to even acknowledge this, knowing Justin’s story too well . . . the beatings, the shaming, the humiliation he’d suffered his entire childhood. “I haven’t felt like I deserved God’s mercy, so too many times I pushed it away.” I wanted to be honest.

“I’m just so angry all the time, full of rage,” he began. “I don’t know.” He paused. “I just . . . Well, you know, my job . . .”

I nodded. Justin’s daily eight-hour job was to scrub feces, blood, and brain matter off the walls and floors in the cells of those who looked for ways to hurt or try to kill themselves. It was a daily occurrence in many of the units.

“There are these two nurses,” he went on. “They yell at me all day long. They want me to work harder, faster. They say things to me such as, ‘Why can’t you do anything right? You are so stupid! Were you raised with pigs?’ ” He looked down, studied his hands, and looked back up at me, an expression that could only be called earnest on his boyish face. “How do I show God’s mercy to these nurses?” he asked softly.

I stared at him. My scrambled mind had no answer to his question. I was shocked that he would ask this instead of look for ways to make the nurses stop yelling at him. The compassion in his voice was palpable, bringing me internally to my knees.

I knew only one thing for sure: I would no longer worry about what to teach these inmates. We are all students here—as we are all teachers to one another on God’s earth.

Somewhere inside of me the lights started to come on. This man was showing me, the student, that God’s mercy is so much more than a concept to be taught. God’s mercy is an experience to be lived out. Justin’s words were mercy personified. His desire to show mercy was God’s mercy lived right in front of me.

My supervisor was right. Together the inmates and I would learn what it meant to walk in God’s mercy. Here in this little room within this prison, we would witness and share the pain of one another’s wounds, accept God’s mercy for the gift that it is, and walk together into God’s healing presence to bring that healing to the troubled world in which we live.

This article also appears in the January 2020 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 85, No. 1, pages 23–25). Click here to subscribe to the magazine.

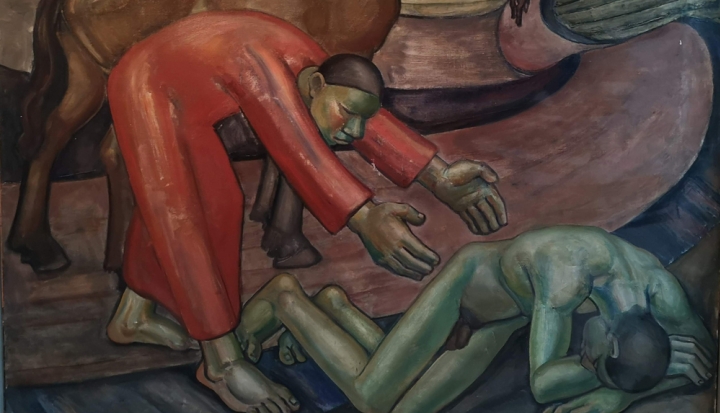

Image: Wikimedia Commons cc

Add comment