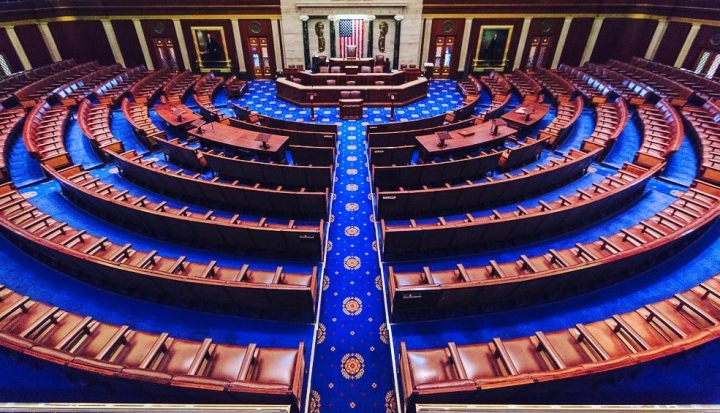

This month, the Speaker’s gavel in the U.S. House of Representatives passes from Catholic Paul Ryan to Catholic Nancy Pelosi. The event comes as a reminder that the Speaker’s gavel has not been out of Catholic hands since 2007.

Largely unnoticed and entirely unheralded, this is an extraordinary development in the history of U.S. Catholicism. For a dozen years, one of the most senior elective posts in the federal government has been held by a once-excluded minority, and not because of the long tenure of a single person who happened to be Catholic. The gavel has passed among three speakers during these 12 years.

Of course, this occurs against a larger backdrop where a majority of seats on the U.S. Supreme Court now are held by Catholics and, for countless other reasons, Catholics have largely secured their place in American life. It hardly should surprise us that no one has noticed this Catholic grip on the Speakership. Catholics are just like everybody else, after all.

That last sentence is largely true. But it also offers us a complicated set of problems to deal with.

For reasons having nothing to do with becoming accepted in the halls of American power and social life, it is good that Catholics are like everybody else. Catholic faith does not teach us that the world is a problem. Instead, the world is a place where nothing is untouched by the hand of a loving Creator.

Catholics cannot hold the world in contempt and still, really, be Catholic. Our faith draws us into the world, closer to one another and even to those who do not share our faith. To seem like everybody else is a vital recognition that, in this created way, we are like everybody else. Each of us is loved by God, just as we are called to love one another.

Yet we are not wrong to hope that Catholic faith might make some difference or distinguish Catholics from non-Catholics. This is the problem that comes into focus when we reflect on the differences we see at work in the political leadership of Nancy Pelosi, John Boehner, and Paul Ryan. For all of the 12 years that the Speakership has been held by Catholics, it would be difficult to name a Catholic way of being Speaker of the House.

That difficulty should give us pause whenever we want to speak with any certainty about Catholic citizenship. Simply being Catholic does not dissolve differences between Paul Ryan and Nancy Pelosi any more than it dissolves the differences between two people sitting in the same pew. Our lives are complex and we all respond differently to circumstances in the light our experience, our judgment, and our consciences. No surprise, we do not always see eye to eye about all sorts of things.

Since 1976 the U.S. bishops have looked ahead to each presidential election by publishing a guide for Catholic voters under the title “Forming Consciences for Faithful Citizenship.” More recent editions have been explicit about “forming consciences” for political decision-making. The timing of that voter’s guide’s emergence is not coincidental. It came with the first presidential election that followed the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in Roe v. Wade to help Catholics be politically active citizens. But, of course, there is a larger story.

In 1976, the Catholic Church had just emerged from the Second Vatican Council. The Council called Catholics to become more involved with the world so that “all the earthly activities of the faithful will be bathed in the light of the Gospel.” That includes political activity.

Of course, even as the bishops were publishing a guide for Catholic voters, they might have read how the Second Vatican Council also cautioned church leaders to “let the layperson not think that pastors are always such experts, that to every problem which arises, however complicated, they can readily give him a concrete solution, or even that such is their mission. Rather, enlightened by Christian wisdom and giving close attention to the teaching authority of the Church, let the layperson take on her or his own distinctive role” (Gaudium et Spes). Bishops and pastors, whose lives are so little like the lives laypeople live in the world, should be learning from laypeople’s experiences.

More than 50 years ago, the Second Vatican Council laid the foundations for a more worldly church where lay women and men would exercise leadership. We know that promise has not yet been fulfilled. It would be easy to blame bishops or perhaps a pope. But I think we would want to notice the differences between Nancy Pelosi and Paul Ryan before we cast too much blame toward a hierarchy.

Worldly problems are complicated. Oftentimes even when we agree about a goal we can disagree completely about how to achieve it. That is in the nature of politics. Almost never is there a clear-cut absolutely right answer to any question. Instead, most times we muddle. We disagree, too. And so, hopefully, we compromise.

Before we demand a “distinctive role” for the layperson, first we all (bishops, priests, and laypeople) need to grow more comfortable about disagreeing and compromising with one another. We need to see those with whom we disagree as being, possibly, partially right. We need to embrace the idea that none of us has all the answers. We must begin from the idea that we need one another, and that fundamental bond of community must hold us together amid our disagreements while we search together for solutions to our difficult problems.

If there is any way to be “Catholic” in political life at all, that is it. Nancy Pelosi, John Boehner, Paul Ryan, you, and I are at our best as faithful Catholics when we approach political questions in that way. That is the vision Vatican II calls us to live out. Bearing witness to that vision with one another in politics and in the church, over and despite our differences, is the only real way to be faithful Catholics in public life.

Add comment