In the past year, terrible secrets in the U.S. Catholic Church have finally seen some light. Thanks to the investigative work of Pennsylvania Attorney General Josh Shapiro and his staff, a grand jury was able to issue a scathing report about predator priests in the Archdiocese of Pittsburgh and the long-time cover-up of the abuse. Police stormed the office of Cardinal Daniel DiNardo of the Archdiocese of Galveston-Houston, the current president of the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, and raided it for information on how he and his staff responded to complaints against Manuel La Rosa-Lopez, a priest accused of sexually abusing teenagers 20 years ago.

More news of these investigations and all that they reveal is certainly to come. Such crimes are not new. Even before 2002, when the Boston Globe broke the first major clergy abuse scandal, priests and bishops abused children and covered it up. But, blessedly, these stories are breaking through, bursting forth like fresh springs from beneath hard, dry dirt. The secret is out.

“Catholics in the pews” have been responding in myriad ways to the scandal that priests, the men so many trust with the care of their deepest, most sacred selves—their spiritual lives—would so deeply harm their brothers and sisters in Christ. And not merely brothers and sisters, but children. Some are closing the door behind them. Others are standing firmly in place.

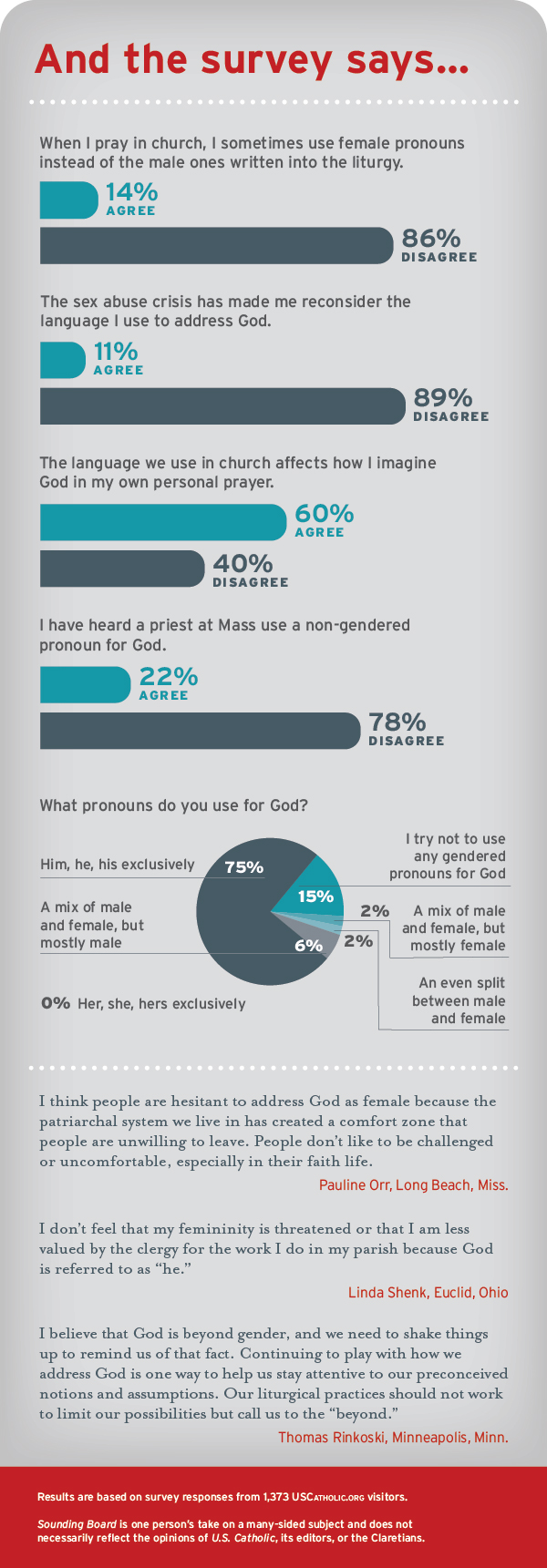

Not a single Catholic (or anyone for that matter) is without an opinion of how the church can respond. I disagree with almost everything I’ve read about the future of the Roman Catholic Church, from how it is resilient and will weather this storm to calls for giving women more of a voice in its governance. Not one of these proposed solutions will change Catholics’ minds about the nature of power as it relates to God.

Yes, the church could ordain women deacons and add more women to papal commissions. Or hire more women to teach at seminaries. Or ordain men later, screen and train them better for ordained ministry. Yes, the church could rethink the required discipline of celibacy. All things I agree would bring about extraordinary change. But at the root of how the church understands itself in relation to God is the language it uses to talk about and to God.

If the church wants to change, we have to stop referring to God in only male pronouns and metaphors. King, lord, he, him, his, father. They are insufficient. Just as female pronouns alone are insufficient, because God is God, ineffable mystery. No single way to talk about God will ever be enough, because God is always more.

But the language we use to address, refer to, and describe the divine is where the rubber hits the road in a life of faith. We must use it, despite the fact that it is never enough. I can’t recall if this metaphor came from Elizabeth Johnson or if I dreamed it up myself while studying her work on precisely this topic in her book She Who Is: Naming “toward” God is sort of like swimming. Each stroke that cleaves into the water is important, necessary, but ultimately you push the water behind you and take another stroke. You have to keep going, or you will sink. In the life of faith, we can never be satisfied with one way to talk about God. If we are, we make idols of our metaphors. Our god becomes a golden calf.

Our institutional church veers dangerously close to worshiping power concentrated in the hands of men. Solely male pronouns and metaphors for the Holy Mystery we celebrate are the gold and cast that reduce God to this idol.

Speaking non-theologically, language shapes the way we think. In her TEDWomen 2017 talk, cognitive scientist Lera Boroditsky points out that this question—whether language can shape our minds or if words are simply tools, stand-ins for a larger reality—has persisted for centuries. But today scientists have collected data on how languages across the globe (there are more than 7,000!) affect how their speakers experience their realities.

For example, the language of an Aboriginal community Boroditsky studied doesn’t have words for what English-speakers call right and left. All things related to direction are phrased in context of the four cardinal directions: north, south, east, and west. Even the way the speakers of this Aboriginal language greet one another is in terms of a cardinal direction. Instead of “How are you doing?” they ask, “Which way are you going?”

As a result of this type of language about direction, this community, and other speakers of similar languages, are extraordinarily well oriented.

“People pay attention to different things depending on what their language requires them to do,” Boroditsky says. “Language guides our reasoning.”

How does Christian language about God guide our reasoning about power, leadership, and gender dynamics? Even if we say God is neither male nor female, to call God “him” guides our internal reasoning. And if God is male, then male is better than female. More powerful. And therefore entitled to that power and the consequences of it (read: the abuse of it in ministry).

But there is a danger in reaching toward female pronouns and metaphors to expand our language for the divine. Social and medical sciences have taught that the social construct of gender is a spectrum. And to use terms such as mother or nurturer for God creates a false dichotomy between male and female, assigning roles to each gender that hurt. Sometimes I wonder if the gender neutral they isn’t the best way to refer to the triune creator, redeemer, and sustainer. We need to likewise dismantle the myth, based on an ancient misunderstanding of reproductive biology, that females are the passive receivers of a seed of life passed to them from males.

I’ve always loved this line from Elizabeth Johnson: “The symbol functions.” She puts it this way:

“What is the right way to speak about God? . . . The intensity with which the question is engaged from the local to the international level, however, makes clear that more is at stake than simply naming toward God with women-identifid words such as mother. The symbol of God functions. Language about God in female images not only challenge the literal mindedness that has clung to male images in inherited God-talk; it not only questions their dominance in discourse about holy mystery. But insofar as ‘the symbol gives rise to thought,’ such speech calls into question prevailing structures of patriarchy.”

And therein lies why I believe that if we want to stop the insidious abuse of power within the church and the world, we have to stop calling God only “him.” We can still call God “him.” We can even still refer to Jesus as “Lord.” But we need more than that.

Perhaps this is why there is fear and anxiety about feminism in the church, about feminine language for God. It threatens the existence of the structures of patriarchy (male power). But the church of Jesus Christ is not the patriarchy. That’s the earthly institution. And we’ve seen where protection of the institution at all costs, even when that cost is a systematic dismantling of the beloved humanity of God’s people, gets us. The symbol has functioned well for so long that as an institution the entire church is swimming in circles—and getting nowhere, sinking, and taking too many innocent people down with it.

This article also appears in the March 2019 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 84, No. 3, pages 23–27).

Image: Unsplash cc via Ruben Hutabarat

Add comment