It’s hard to argue that the arrival of Europeans in the Americas was anything other than a disaster for indigenous people. The numbers are disputed, but the outcome is not: After a handful of centuries, by the turn of the 20th century hundreds of societies representing millions of people had been reduced by violence, famine, disease, and dislocation to a few hundred thousand people.

It is upon this suffering that the modern nations of North and South America have been constructed. In our own enlightened times the crush of encroachment on the so-called New World’s indigenous communities continues, often for the same reasons and with some of the same tactics.

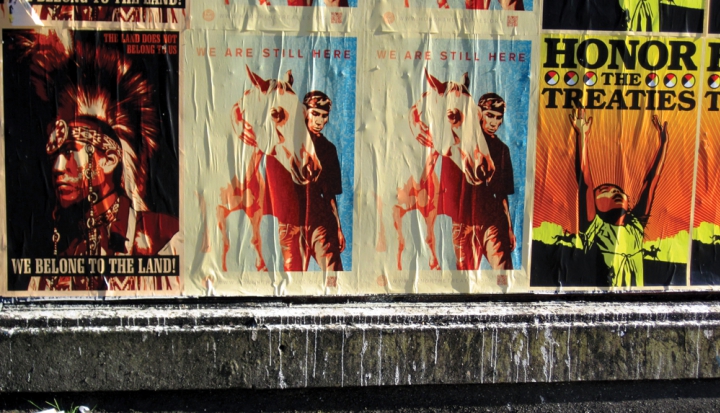

The rule of law is supposed to mean something in Western societies. Yet in the United States alone, court decisions, legislative rewrites, and brute acts of removal and conquest have meant that every one of the 500 or so treaties signed by U.S. authorities with native people has been violated, including an 1851 treaty that should have prevented the seizure of indigenous land that is now the disputed terrain through which the Dakota Access pipeline unwinds. Standing against that pipeline’s extension has been the Standing Rock Sioux community.

That particular dispute garnered global attention, but all over the world, from the forests of Brazil through the rivers of Central America up to the tar sands and mountains of Canada, indigenous resistance continues at the intersection of the most pressing issues of our times: climate change, fossil fuel extraction, and the connective tissue of geopolitical policymaking and influence peddling. The clash revives old claims to tribal lands or propels modern communities to seek new protections for tribal rights against a contemporary colonization—the relentless press of mining, timber, or fossil-fuel interests.

The strategy of these forces differs little from the 19th-century cheerleaders of expansion and exploitation. These days the press of the oil and natural gas markets is used to justify contemporary infringements while mining giants seek to overwhelm indigenous rights with the familiar rationalizations of the primacy of development and modernity over “unproductive” indigenous land practices.

In Brazil the Waiapi resist government efforts to open their land to mining companies, beginning resource extraction just about guaranteed to leave them poorer and their land desecrated. In British Columbia the Ktunaxa people defend Qat’muk—their name for the lands in the central part of the Purcell Mountains—from developers determined to build a ski resort. In Honduras indigenous communities struggle against mega-dam projects that would inundate their lands.

The church has much penance to make for injustices it inflicted on indigenous people or the thousands of such acts it provided spiritual cover for. Pope Francis met with indigenous people in February 2017 to offer his support to their struggle, highlighting the spiritual lessons offered by these communities and their commitment to what Francis has called care of creation.

The central issue for development within indigenous territory, he said, is reconciling social and cultural change with the protection of the “particular characteristics of indigenous peoples and their territories.”

“In this regard,” the pope said, “the right to prior and informed consent should always prevail.”

Informed consent may not sound like too high a bar to set when treaty-making between two sovereign powers. But for the indigenous people of our time, it is a cultural- and life-sustaining standard in new encounters with avaricious corporate or political forces. Remaining humbly respectful of it is the least hemispheric newcomers should insist upon as a small amends for a tawdry continental past.

Add comment