Religious horror is a film genre in its own right, and Rosemary’s Baby and The Exorcist are among my all-time favorites. But even horror movies that aren’t explicitly religious stoke my religious imagination, exploring questions of who suffers and why and to what end. The best aren’t the goriest but rather those that articulate or give shape to our deepest unseen fears.

The Babadook embodies grief as a monster in a top hat that torments a bereaved mother and son. The Shining is a story of marriage and family life thwarting creativity—to the point of murderous insanity. It Follows explores the connections between eros and thanatos through the lives of teens who sexually transmit a deadly plague—the only cure for which is to pass it on. Much has been made of that connection between sex and death in teenage slasher flicks like A Nightmare on Elm Street and Friday the 13th, but even highbrow art-house offerings communicate a deep cultural anxiety about monogamy, pregnancy, and motherhood.

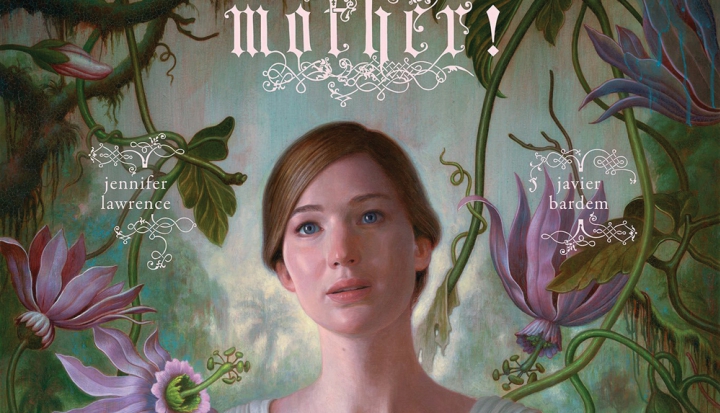

In Mother! Darren Aronofsky (director of Requiem for a Dream, Black Swan, and Noah) pushes these tropes well past absurdity. Critics have made much of the film’s biblical and ecological allegory, which Aronofsky takes to laughable extremes. The film’s frenetic climax plays Catholic imagery like a Jack Chick tract brought to life—crazed masses of cannibalistic lemmings eating sacrificed human flesh in a trance-like state of desperation to commune with the transcendent. Their hunger is real and almost innocent, and they press in like mindless zombies. It’s beyond gross, but it’s not scary.

Mother! might be more effectively described as pitch-black comedy rather than horror. (Writing in the New York Times, A. O. Scott notes that if Aronofsky “didn’t take himself so seriously, he could be a great comic filmmaker.”) But I found it even more compelling as a domestic drama, the story of a marriage that devolves into a live-action Hieronymus Bosch painting, the devastated wife standing in the ruins of all she’s created before she finally finds a Zippo and torches the place.

A woman (Jennifer Lawrence) and her husband (Javier Bardem)—he refers to her only as his “Goddess” and is known only as “the Poet”—live in a gorgeous old Victorian in the middle of a quiet meadow. The Poet suffers from writer’s block, while the young and beautiful wife spends all her time wandering around in her nightgown making the house his “paradise.” I was already feeling the Goddess’ pain before the strange couple (Michelle Pfeiffer and Ed Harris) showed up, thinking they’d stumbled on a charming bed and breakfast. Without asking his wife’s permission, the Poet invites them to stay as long as they’d like.

The Goddess, bewildered, goes on trying to make their home beautiful and to nourish the people who live in it—cooking, cleaning, singlehandedly renovating each room. Meanwhile the rude guests have sex with the door open and smoke in the house even after being asked to go outside. The woman tells the Goddess she needs to buy sexier underwear. They’re meant to be Adam and Eve, I suppose, but they struck me as in-laws from hell.

The obnoxious couple’s children soon arrive, and a family squabble ends Old Testament style when one son murders another while the Goddess looks on, helpless. The Poet leaves her alone in the house, despite knowing the murderer is still at large, so he can accompany their guests to the hospital. Lawrence’s face registers the horror of marital disregard and abandonment before she resigns herself to mopping up the blood in the guest room.

The Poet is charming and magnanimous—to everyone but his wife. For her, he harbors a barely concealed resentment for stymying his creative powers even as she devotes all her energy to creating the perfect conditions for his flourishing. He thrives on the adulation of others, and he’s never satisfied, never satiated.

Married life in the meadow is lonely. When he does create a new work—in tandem with the creation of their first child—and crowds of admirers begin to descend on their paradise, literally dismantling it and taking pieces of lumber to “prove we were here,” the ecological implications certainly weren’t lost on me. But watching Jennifer Lawrence stand helplessly confused amidst the ruin, I recognized a story much more personal than cosmic allegory.

It’s not just the earth that’s wrecked by human callousness. It’s the woman’s body. A friend, also a wife and mother, saw the film’s escalating home invasion—encouraged by the Poet, who continues to sign autographs and calls out that everything can be replaced—as the film’s most compelling metaphor, a metaphor for motherhood.

But she didn’t feel comfortable admitting this to many people besides me. As Catholic mothers, we’re expected to experience and project motherhood in certain ways. Invasion and destruction aren’t among them.

After the Goddess gives birth to their son, amid the chaos of watching her house be destroyed, she holds him protectively against her breast, and there are a few moments of peace until the Poet demands to hold him and she refuses. The Poet will sacrifice everything on the altar of his ego—his home, his wife, and even his child.

This seems less a gesture to the Christian God than to the artist as succubus. Everything in the Poet’s life is material, even his son. He pulls up a chair and sits, staring at his wife, unblinking, and a terrifying stand-off ensues. She struggles to stay awake, holding the chirping newborn, who alternately suckles and sleeps. But it’s inevitable. She falls asleep.

I thought of the paintings I’ve seen of the Virgin Mary confronted with the implements of Christ’s crucifixion, the fear in her eyes. But I also remembered the intensity of new motherhood, the loneliness, the fear, the exhaustion, the weight of responsibility, and the horrible feeling of being constantly watched and judged. The consequences for failure had never before felt so high.

When she wakes up, the Goddess’ arms are empty. It’s the only scene in the film I found truly scary.

This article also appears in the January 2018 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 83, No. 1, pages 38–39).

Add comment