The Second Vatican Council’s Pastoral Constitution on the Church in the Modern World begins by underscoring the church’s humanity and empathy:

“The joys and hopes, the grief and anguish of the people of our time, especially of those who are poor or afflicted, are the joys and hopes, the grief and anguish of the followers of Christ as well. Nothing that is genuinely human fails to find an echo in their hearts” (Gaudium et Spes).

Promulgated over 50 years ago, the insight that believers cannot exist apart from “the people of our time” and the “genuinely human” continues to challenge those who identify as Catholic.

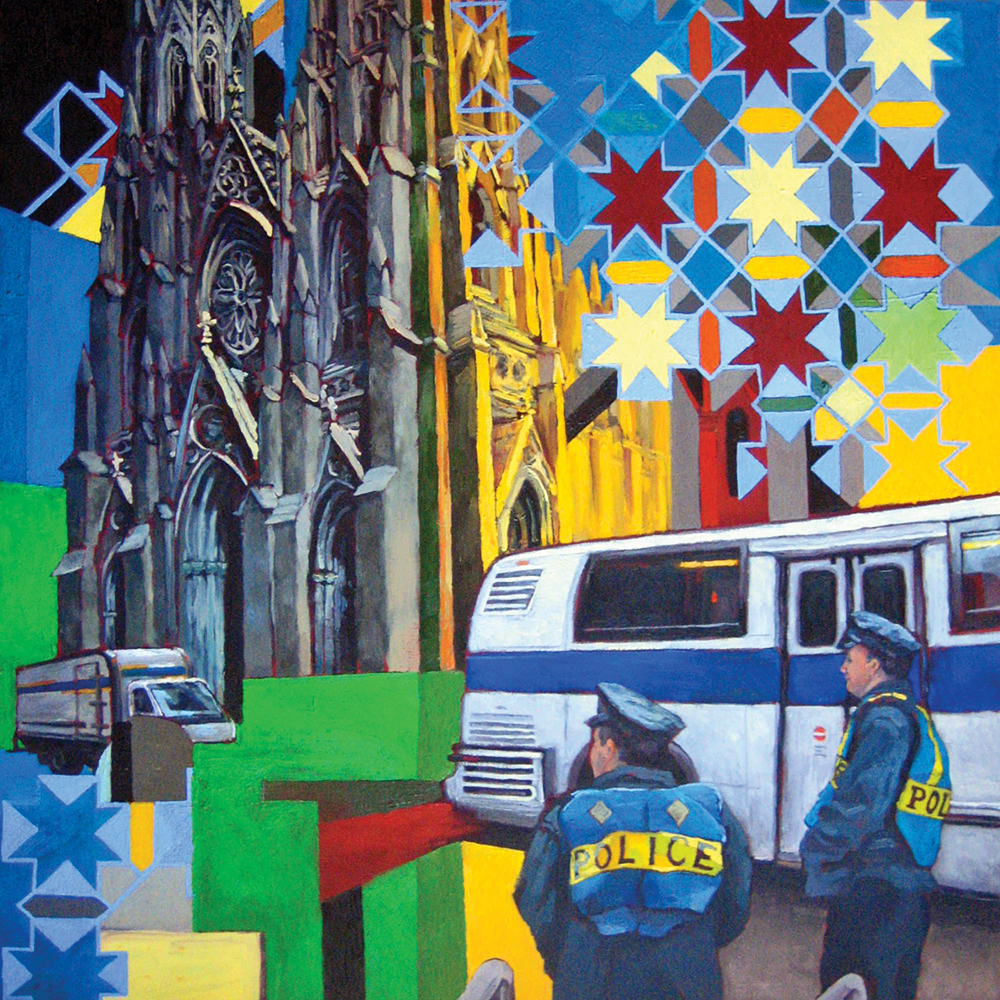

Congregation of the Blessed Sacrament Father John Christman explores the Council’s admonition in a series of paintings named for this text. Each of Christman’s surfaces employs a similar vocabulary: a church building, an activity, and a portion of a pattern. The depictions of these structures that house the church (the people of specific local communities) act as bridges between a hierarchical understanding of the church and the Council’s emphasis on the dignity of all believers. This might be a church less doctrinally sure of itself, more comfortable to see itself as mystery.

The ecclesial architecture illustrated has European roots. Neither St. Patrick’s Cathedral in New York nor St. James Church in Chicago represents a distinctly American style. Santa Cruz Church in Manila, destroyed with the rest of the city in 1945 and rebuilt in 1957, resurrects Spain’s colonization of the Philippines (1521–1898). Likewise, St. Joseph’s Cathedral in Beijing records the presence of foreign powers struggling to establish their rights to Chinese goods and markets and the religious system that accompanied them.

These buildings document political posturing, cultural hegemony, and a theology tied to both place and era. All are celebrated regional, national, or international monuments. They also encode a church whose buildings were designed to impress rather than welcome, to separate into ranks rather than indicate unity.

Could these buildings be proposed in 2017? Not if new construction projects seek to draw from current architectural language a way to express the Council’s comprehension of the church’s mission in the world.

This presumes several capacities. One of these, the ability to think of one’s culture as good, is more elusive than it might appear. Decades after Sacrosanctum Concilium (The Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy) taught that “the church has no wish to impose a rigid uniformity . . . rather does she respect and foster the genius and talents of the various races and peoples,” architectural templates from other places and times are preferred, at times, because “looking like a church” becomes the determinative criterion.

Such choices are reminders that our colonized past and our biases live within us, that we struggle to see the present as a time of blessing. Author Annie Dillard dissuades us from such an assessment: “It is a weakening and discoloring idea, that rustic people knew God personally once upon a time . . . but that it is too late for us. In fact, the absolute is available to everyone in every age. There never was a more holy age than ours, and never a less” (For The Time Being, Vintage).

St. Sulpice itself stands as a witness to interrupted plans and changing visions, a pastiche of styles and ideas triggered by everything from the French Revolution to a succession of architects. Christman superimposes a construction crane upon the building’s likeness, a reminder the second largest church in France was finished by the proverbial writing straight with a crooked line. This painting seems to admonish us not to think in terms of finishing, of completing a consistent project. For both faith communities and individuals, carefully arranged plans are disrupted by the unexpected.

Though dated, these edifices also function as icons of familiarity and stability. Day in and day out, St. James Church witnesses Chicagoans traveling via the elevated “L” trains. In China, St. Joseph’s Cathedral becomes the backdrop for the resourceful transportation of goods. When these houses of worship offer human connections, “the joys and hopes . . . of the people of our time” find a place there. When these buildings shelter a range of gatherings and activities, they exist as more than landmarks.

Often significant moments become an entrée. Weddings and funerals, first communions and quinceañeras, Sunday Mass and other sacraments might invite believers, seekers, and guests to enter these structures. Sometimes these predictable events give way to the incomprehensible.

By picturing police in front of St. Patrick’s Cathedral, Christman summons the specter of September 11, 2001. That day forced

the United States of America to rethink what is possible; that day challenged the church in New York and surrounding dioceses to address the “grief and anguish” of people traumatized by an unimaginable horror.

Cities and nations face challenges to address basic human needs. The electrical lines interrupting the façade of Santa Cruz Church suggest infrastructures providing power and the inequality of its availability; the cooling towers paired with St. Joseph’s Cathedral remind us of our nuclear age—its potential destructive power and unanticipated disasters. Perhaps one of the vital gifts the church offers the world is posing questions about access and profit. Who gets to use and who economically benefits from the earth’s resources?

The third component of each of these artworks is a portion of a repeat design. Whether drawn from tiled floors and walls, stenciled surfaces, or printed fabrics, these patterns, both decorative and soothing, suggest predictability and order. But these qualities fade away as Christman selects an irregular fragment of these matching modules; their partial presence suggests a process underway or abandoned, something falling apart or impossible to complete. Sometimes Christman introduces irregular patches of color into these conversations; these might advocate for emotion, intuition, or improvisation, the presence of God, the breath of God’s spirit.

As a series labeled The Church in the Modern World, we are invited to interpret the significance of these juxtaposed elements and the commentary they suggest. Likewise, these paintings invite us to consider other possible combinations that mimic Christman’s visual system. More important, we are reminded of the holy charge to make room in our living church for all that is “genuinely human.”

This article also appears in the March 2017 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 82, No. 3, pages 26-31). Click here to subscribe to the magazine.

Add comment