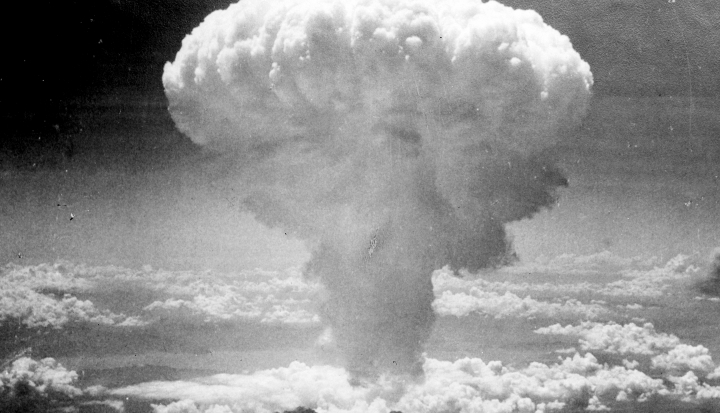

St. John Paul II, while visiting Hiroshima, Japan—a city where more than 80,000 lives evaporated in an instant—said in February 1981, “To remember Hiroshima is to abhor nuclear war. . . .To remember Hiroshima is to commit oneself to peace.’’

When President Barack Obama made his historic visit to Hiroshima in May, his mind was likewise on a world liberated from the menace of nuclear weapons. He spoke of humanity’s “core contradiction,” or the fact that “the very spark that marks us as a species, our thoughts, our imagination . . . our ability to set ourselves apart from nature and bend it to our will—those very things also give us the capacity for unmatched destruction.”

The speech at Hiroshima makes a bookend of sorts for President Obama. Early in his first term, in a speech in Prague in 2009, he sought to restart what had been a broadly successful nuclear disarmament race between the United States and the old Soviet Union. After a series of SALTs and STARTs (Strategic Arms Limitation Talks and Strategic Arms Reduction Treaties, respectively), the nuclear superpowers by then had vastly reduced their nuclear arsenals and seemed on the path to complete disarmament.

But that progress has stalled. By some measures, despite his words of regret (but not direct apology) in Hiroshima, the president has been heading in the other direction on nuclear weapons.

According to the Department of Defense, the U.S. nuclear stockpile numbered 4,571 warheads at the end of 2015—about 15 percent of its Cold War peak in 1967. But the number of weapons dismantled in 2015 was 109, the lowest figure since 1980. Worse, the Obama administration has been preparing for an estimated $1 trillion nuclear weapons modernization program that may provoke a renewed nuclear arms race and increase pressure for a nuclear test. Obama’s investment in nuclear modernization may also lead to a new generation of small-yield, tactical nuclear weapons that military strategists will be tempted to use on a future battlefield.

It seems what is dearly wanted in the international dialogue over disarmament, as the president suggested in Hiroshima, is a louder voice for moral reason. These days, that could be coming from the Catholic Church.

Since 1963’s Pacem in Terris (On Peace) the church has rejected the use of nuclear weapons—indiscriminate weapons of mass human and ecological destruction—as morally indefensible. The church has maintained a qualified acceptance of nuclear deterrence as long as that policy is deployed as a diplomatic stepping stone to complete disarmament. But after years of inaction, patience is wearing thin and deterrence itself has come to seem as morally indefensible as the bomb.

Since 2015 the church has stepped up its criticism of deterrence and urged greater efforts toward complete disarmament. In May church leaders met in London to continue that dialogue. San Diego Bishop Robert McElroy was among the participants at that conference. In an interview on “America This Week” on Sirius radio, McElroy said the United States has a special responsibility to promote disarmament.

“What we have to take ownership of,” he said, “is the fact that we’ve been the only nation to use nuclear weapons and that it had a horrendous human cost.” He said the United States could honor the suffering it had created in Hiroshima through aggressive efforts to build a nuclear-free world.

In Hiroshima, President Obama concluded his remarks by urging “those nations like my own that hold nuclear stockpiles” to have “the courage to escape the logic of fear and pursue a world without them.” Toward that end, the president will have a reliable ally in the church.

This article also appears in the August 2016 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 81, No. 8, page 42).

Add comment