At Jesus’ birth, shepherds came to visit him, followed soon after by the wise men, right? Actually, not quite. There are two separate versions of Jesus’ birth in the New Testament. This happens fairly often in the Bible; both the Old and New Testaments contain numerous repeated and similar-sounding stories.

The Gospels of Matthew and Luke each give their own account of Jesus’ birth. To be sure, they have important similarities: Both include Mary’s virginal conception, identify Jesus as a descendant of King David, and name Bethlehem as Jesus’ birthplace. The two sound similar enough that they meld together in many people’s minds. Yet the stories diverge in key places. Luke begins with a Roman census, which leads to Jesus’ birth among livestock and welcoming into the world by angels and shepherds. Matthew’s rendition, in contrast, doesn’t involve a census, manger, or shepherds, but introduces the Eastern wise men bearing gifts, the star, Herod’s murderous plot, and the holy family’s escape to Egypt.

Like many other repeated Bible stories, these versions of Jesus’ birth can be explained by the formation of the canon—the official list of books that make up the Bible. The New Testament most likely began as oral and then written stories about Jesus and the apostles, which were circulated among the early churches until the second century. From that point to the Council of Trent in the 16th century, the church gradually came to a consensus about which writings were inspired and should be counted as “scripture.” Catholics believe that it was a divinely guided historical process, which involved much reflection and debate. Because the final product was made up of many different sources—like the four gospels—the process built in a lot of parallel stories about Jesus’ life and ministry.

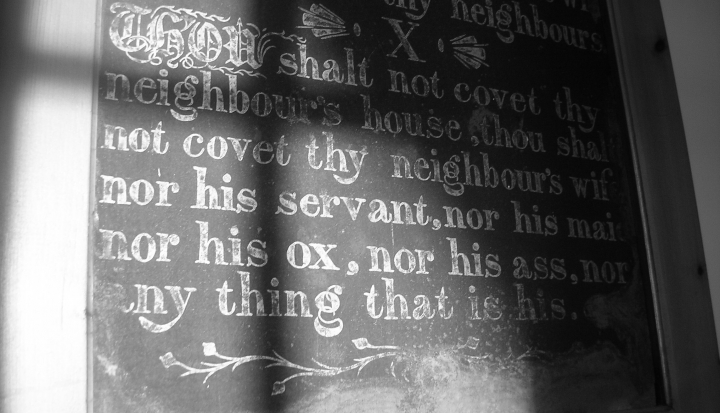

Even by Jesus’ day, the Hebrew scriptures (or Old Testament) already contained hundreds of years’ worth of compositions by many hands and perspectives. These scriptures included alternate tellings of some stories as well. In the Old Testament, there are actually two versions of the Ten Commandments (Exodus 20 and Deuteronomy 5). These are almost the same—with some small but meaningful differences. Most scholars agree that Deuteronomy 5 reinterprets an earlier list, or the one from Exodus. For instance, in Deuteronomy the Israelites are told to keep the Sabbath holy because of their deliverance from Egypt, while in Exodus this command is linked to the creation story and the fact God rested on the seventh day.

While the different gospel stories resulted from different sources being put into the Bible together, the different Ten Commandments are more likely an example of inner-biblical interpretation—another reason Bible stories often sound similar. Inner-biblical interpretation refers to the long tradition of scripture referencing, revising, and further interpreting older parts of the Bible. In other words, faithful people began interpreting and reinterpreting scripture long before the Bible was finished, and some of those writings were included in the final product. Jesus routinely quotes from and reinterprets the Hebrew scriptures, and the same thing happens within the Old Testament itself.

These are just two examples; the Bible is full of spirited dialogue between authors who seek to understand and interpret the word of God. We are doing much the same thing today: trying to interpret the Bible and understand how it fits into our daily lives.

This article appeared in the December 2015 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 80, No. 12, page 48).

Image: Flickr cc via Walt Jabsco

Add comment