On Thursday night, November 20, 2014, President Barack Obama announced his executive action limiting deportations of undocumented immigrants to the most criminal cases, thereby providing freedom and hope to some 5 million people. In doing so he not only launched a process of compassion to many persons seeking a better life for themselves and their families, he also dramatically challenged Congress to pass a law encompassing broader immigration reform.

Such focused confrontation from a base of power to call forth social responsibility from political leadership is something that Obama learned as a community organizer in Chicago. It was the fruit of a once powerful movement known as Catholic Action. Chicago has been a fount of community organizing since the Great Depression, when the Catholic Church united with organized labor in the Back of the Yards neighborhood on the city’s south side.

With the strong support of Cardinal George Mundelein and his auxiliary bishop, Bernard James Sheil, the Back of the Yards Council provided a voice for the immigrant communities of that impoverished neighborhood. They collaborated with community organizer and activist Saul Alinsky, whose friendship with Catholic philosopher Jacques Maritain and collaboration with Catholic Church leaders would enrich subsequent community organizing efforts. (Even Archbishop Giovanni Montini, the future Blessed Pope Paul VI, would confer with Alinsky on community organizing in Italy.)

This example of grassroots social justice, of collective listening to the cry of the poor, would have the principles of Catholic Action as its philosophical and theological base. The future U. S. president was a student and practitioner of this philosophy and theology. It is no accident that Obama’s first office was located in a Catholic church.

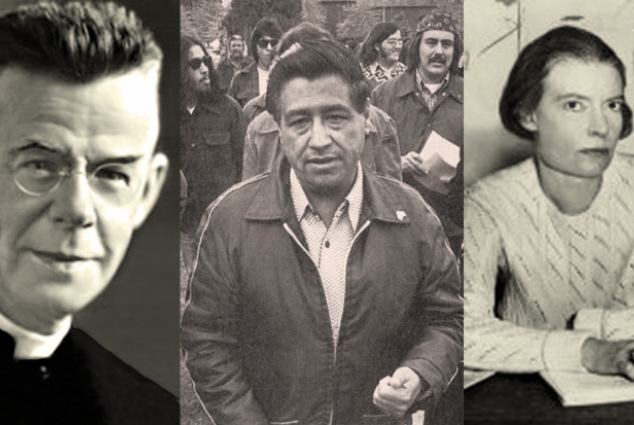

I pray for a return to Catholic Action. My own first contact with Catholic Action came in 1972, during my seminary internship year at our Paulist mother house, St. Paul the Apostle Church on Manhattan’s West Side. I was part of the parish team hosting a rally in our spacious church basement for Cesar Chavez and his United Farm Workers. Chavez was quick to point out that among the 2,000 participants there that day was a “saint,” Dorothy Day.

Both Chavez and Day had been heroes of mine throughout my formation in the culturally formative 1960s. So when one of the UFW members addressed our parish Cursillo group the next morning and mentioned that both he and Chavez were cursillistas, I was motivated to experience the movement myself, even though I’d been a bit hesitant up to that point. I would later meet the Cursillo founder, Eduardo Bonnin.

As a young man in Spain in the 1940s, Bonnin, I learned, belonged to something called “Catholic Action.” He and a group of other young men, disturbed by the absence of young adults in church participation, made a pilgrimage to the shrine of St. James of Compostela along the famous Camino de Santiago. After a profound conversion experience, they came up with the Cursillo method of transforming society through small communities of committed Christians.

The term “Catholic Action” described both a movement and a mentality. As a movement, Catholic Action had its beginnings in the latter part of the 19th century, when people proactively took measures to counteract the anti-clericalism running rampant, especially throughout Europe. As the church entered the 20th century, Catholic Action became more of an organized movement in which laypeople, collaborating with members of the hierarchy, worked to bring Christ and the social teachings of the Catholic Church into the greater society.

Joseph Leo Cardijn, a Belgian priest and later cardinal, was the godfather of the movement. In 1919 Cardijn founded the Young Trade Unionists, which later became the Young Christian Workers—the quintessential model for Catholic Action. Peter Maurin, who cofounded the Catholic Worker movement with Dorothy Day, penned an essay in 1933 titled “Blowing the Dynamite,” which captures the philosophy of Catholic Action. Cardijn referred to Maurin’s thought as “the purest spirit of the Gospel.” Maurin wrote:

Writing about the Catholic Church, a radical writer says: “Rome will have to do more than to play a waiting game; she will have to use some of the dynamite inherent in her message.” To blow the dynamite of a message is the only way to make the message dynamic. If the Catholic Church is not today the dominant social dynamic force, it is because Catholic scholars have taken the dynamite of the church, have wrapped it up in nice phraseology, placed it in an hermetic container and sat on the lid. It is about time to blow the lid off so the Catholic Church may again become the dominant social dynamic force.

It would be this “blowing the dynamite” approach to proactive Catholicism that would characterize the highly diverse groups coming under the umbrella of Catholic Action. These would include, in addition to the Young Christian Workers, the Young Christian Students; the aforementioned Cursillo movement, itself giving birth to numerous parish and youth encounters; RENEW International; the Legion of Mary; Sodalities; the Christian Family Movement; the various community organizing groups like COPS (Communities Organized for Public Service) in San Antonio, whose founder, Ernesto Cortes, would later train the young Barack Obama in Chicago; and Friendship House in Harlem (an early influence on Thomas Merton).

Cardijn also designed what would become the predominate methodology of Catholic Action, summarized by the three titles see (observe), judge, and act. This approach would make its way into Pope John XXIII’s 1961 encyclical on Christianity and social progress, Mater et Magistra. “There are three stages which should normally be followed in the reduction of social principles into practice,” he wrote. “First, one reviews the concrete situation; secondly, one forms a judgment on it in the light of these same principles; thirdly, one decides what in the circumstances can and should be done to implement these principles. These are the three stages that are usually expressed in the three terms: observe, judge, act.”

To put it another way, we see the reality around us—with all of its problems and challenges—with the eyes of Christ. We discern a response to these problems and challenges with the mind of Christ, using scripture and the teachings of the church. And we implement our responses in action as the body of Christ.

In addition to being a movement, Catholic Action is also a mentality. The move to bring Catholic social teaching into the public square motivated Catholics like Msgr. John A. Ryan of the Catholic University of America, whom many have called the prophet of the New Deal, and Paulist priest John J. Burke, founder of the National Catholic Welfare Conference, the precursor to the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops. In fact, the current Catholic Campaign for Human Development began with the guiding principles of Catholic Action. Even Hollywood has felt the influence of the Catholic Action mentality. Movies of the 1930s, ’40s, and ’50s, including Boys Town, The Keys of the Kingdom, Going My Way, and On the Waterfront, highlighted the role of the socially conscious Catholic priest.

For a contemporary example of a priest directly formed by Catholic Action, take the prophetic and spirit-filled Msgr. Thomas Kleissler, whose influence permeates current Catholicism. In his recent autobiography, Beyond My Wildest Dreams: From Local Ministry to Worldwide Mission (RENEW International), Kleissler describes a boyhood experience that took place at the school library one rainy day.

He recalls picking up a pamphlet about Father Cardijn and the Young Christian Workers, where he learned the approach of “observe, judge, act.” That approach, along with a lifelong passion for justice and service to the poor, would dominate Kleissler’s work as a priest, from leadership in the Christian Family Movement to active participation in the civil rights movement. It also led him to found (with Msgr. Tom Ivory) RENEW International, a process that perhaps more than any other would build up the church out of base communities of parishioners committed to ongoing personal conversion to Jesus and connecting faith to everyday life.

To put it mildly, Catholic Action helped to place the foundation for lay involvement in church life that was so prominent in the Second Vatican Council, but there has been a subsequent lull. Now is the time for a revival and renewal. Hopefully the new evangelization of St. John Paul II, Pope Benedict XVI, and Pope Francis can spark such a revival and renewal. Certainly the caring witness of Pope Francis, and his magnificent apostolic exhortation The Joy of the Gospel, provide reasons for hope.

America today is desperately in search of a way to embrace the motto e pluribus unum, “one out of many.” It is precisely Catholic Action, both as a movement and a mentality, that offers the best opportunities to unite the polarized pro-life and pro-poor camps.

Recently I participated in a unified effort in Texas coordinated by Catholic Charities of the Diocese of Brownsville. The purpose was to serve immigrant children and families coming across the U. S.-Mexico border from Central America in a desperate flight from poverty and threats of ruthless gangs and drug traffickers. There at the Rio Grande, at Sacred Heart Church in McAllen, Texas, were volunteers from all walks of life and ideologies.

We came from the faith communities, the medical profession, various levels of government, the legal profession, the local food bank, and even the bus station. We were there working together to meet the basic humanitarian needs of God’s precious children. There, in a border town filled with a cross section of the human race, I rejoiced to see a return to Catholic Action.

This essay appeared in the July 2015 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 80, No. 7, pages 36–38).

Image: Joseph Leo Cardijn, Cesar Chavez, and Dorothy Day, all public domain.

Add comment