We sometimes say of people that they’ve been “to hell and back.” Christianity says the same thing about our Savior.

The statement is found in the Apostles’ Creed, a profession of faith with origins that may go back to the questions asked of candidates for baptism in the late second century. It reminds us that the saving power of Christ is for all times and all peoples, even those who entered and passed from human history prior to his death and resurrection.

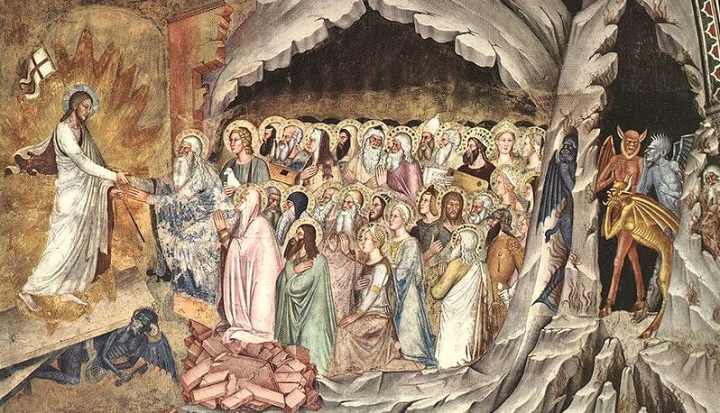

This doctrine is also known as the “harrowing of hell,” from a medieval English word used to describe the plundering and ravaging that takes place during times of war. It proclaims total victory of the divine conqueror over Satan—unable to escape even though he is in his own abode in hell. Christ takes the fight to the devil himself and releases the just who have long awaited the day.

Like many Christian beliefs, this one springs not so much from the exact teaching of Jesus recorded in the gospels but from the experience of him as God’s appointed agent of redemption.

Early Christians asked: If Christ is the salvation of all, how does he save those who lived before us? Those righteous who believed in the God of Jesus but who lived before the Messiah’s appearance in human history came to be known as “the church from the time of Abel.”

Theories abounded with regard to how Christ might accomplish their salvation, but the primary idea was that, until redemption had been completed in his death and resurrection, they could not know the joys of being in God’s presence. They were believed to reside somewhere in hell or in some outer chamber of the underworld, deprived of the final benefits of Christ’s redemptive work.

Such understandings appear to be implied in certain New Testament texts, especially with regard to the time between Jesus’ crucifixion on Friday and the discovery of the empty tomb on Sunday.

A prime example is found in Luke 16, where an uncaring, wealthy man is assigned to the netherworld while a suffering beggar is given rest in the “bosom of Abraham” (Luke 16:22). Acts 2 mentions more than once that God did not abandon Christ to the netherworld, and the idea of death as a pit or abyss occurs in other places in the New Testament and throughout the Hebrew scriptures.

During the time of Jesus’ ministry, Jewish notions of death included the idea of sheol, the underworld home of the dead. It was described quite literally with the same depictions that one would apply to a grave: a place of dust, worms, inactivity, and decay.

The first Christians had to reckon with this reality. As Yahweh was believed by this time to have power even over death (as portrayed in the parable of the dry bones in Ezekiel 37), Christ Jesus came to be portrayed as the agent who secured Yahweh’s final victory over sheol, even for those who were already there.

This article appeared in the March 2013 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 78, No. 3, page 46).

Have a question you’d like to get answered? Ask us at editors@uscatholic.org!

Wikimedia photo cc by Web Gallery of Art

Add comment