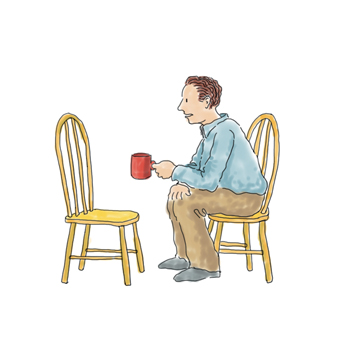

What’s so odd about talking to God over a cup of coffee?

It’s not often that you turn on the radio and hear someone talking about you—well, not you personally, but someone like you. That was the reaction I had listening to National Public Radio’s Terry Gross as she interviewed Tanya Luhrmann, a Stanford University anthropologist who had just published When God Talks Back: Understanding the Evangelical Relationship with God (Knopf). Luhrmann had been intrigued when she met a woman who “had coffee with God” and “talked about God as if he were a person,” so she began participating in a prayer group at a location of the evangelical Vineyard Church to see what was going on.

I was intrigued as well, since I have been talking to God as long as I can remember, and I know a lot of other people who have, too. I was mostly interested in the fact that such a relationship with God—“as if he were a person”—was such an object of curiosity.

NPR’s Gross at times sounded a little incredulous (though always respectful): “What’s the difference between the imaginary friend that you’re supposed to outgrow,” she asked, “and this approach to believing that . . . God or Jesus is like your friend, your buddy?”

Luhrmann was quite open to the possibility: “I wouldn’t call myself a Christian, but . . . through these practices of praying and thinking about the stories that were being told in church, I would have these moments of joy that I would call God.”

I turned off the radio a bit thunderstruck that I had just heard a story about the possibility of a personal relationship with an unconditionally loving God at a church that was founded in the 1970s, as if this was something unique to the Vineyard or to American evangelical Christianity. The only thing I could ask myself was: What the heck have the rest of us been up to all this time?

Luhrmann knew that she was on well-trod ground, noting that the church fathers and C. S. Lewis spoke of an “imagined conversation with God” as a path to prayer. St. Augustine’s famous Confessions is just such an “imagined conversation,” carefully documenting all the ways God had led the great theologian step by step to faith.

While Luhrmann’s subjects at the Vineyard imagined themselves having coffee with God, mystics such as Teresa of Ávila and John of the Cross experienced decidedly more intimate encounters with the Holy One. In our time Dorothy Day’s “personal relationship with God” led her to a life among the poor, while Thomas Merton’s landed him at a Trappist monastery. God inspired L’Arche founder Jean Vanier to share his life with people with mental disabilities and Sister Dorothy Stang to shed her blood to defend the poor of the Amazon.

Our lives are no doubt filled with lesser-known grandmothers and uncles and coworkers and teachers whose lives are no less constant responses to God’s voice, even if their faithfulness doesn’t draw headlines. Indeed it has long been a Catholic truism that God seeks every single human being out for this kind of relationship, eternally eager to befriend us. Our particular Catholic spin on this mystery is the necessity of discerning God’s message within the community of faith rather than going it alone.

Luhrmann’s academic curiosity and Gross’ journalistic interest point to an opportunity: People both wonder about and hunger for a uniquely personal experience of God’s unconditional love.

What is a little disappointing is that so many Christian communities, beset by the challenges of institutional maintenance and survival, are ill-equipped to help people discover that relationship. After all, what is the purpose of religious institutions if not to facilitate that personal encounter with God? Without that foundation, Sunday Mass can quickly become empty ritual and even service to the poor little more than social work.

The good news is that we have all the resources we need to invite others to have their own experience of God. The best way to start may just be telling them—and each other—about our own.

This article appeared in the June 2012 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 77, No. 6, page 8).

Image: Tom Wright

Add comment