The church isn't always the loving Body of Christ we imagine ourselves to be. James Carroll nevertheless defends our faith in God, who saves us imperfect human beings from ourselves.

One of the best people I know volunteers in a church-sponsored soup kitchen in a big city. I visited him recently and was deeply moved to watch as he and other volunteers graciously and respectfully served their "guests," beleaguered men and women who otherwise are treated as social outcasts.

"I love this," my friend said, adding that he clung to his Catholic faith mainly because of its central meaning as sponsor of service and compassion. I knew what he meant and shared his gratitude for all the good work that is done by Roman Catholicism across the globe-service and compassion offered without strings.

That Catholics have taken to defining the church as a center of social justice is a post-Vatican II form of the ancient understanding of love as the hallmark of Christian identity. "God is love, and those who abide in love abide in God" (1 John 4:16).

"Justice," the scholar Cornel West says, "is what love looks like in public." This commitment to justice as the key note of Catholic identity is reflected in the idealism of many young Catholics who join anti-poverty volunteer organizations, or in the multiplication of "social justice" committees in Catholic parishes, not to mention the momentous affirmations of Catholic social justice that have lately been a mark of Vatican declarations and teachings of various bishops' conferences.

But is it true? "They'll know we are Christians by our love, by our love"-or so the snappy hymn goes. Jesus defined the greatest of the commandments as loving God and loving your neighbor. Christians immediately claimed that as setting the church against Judaism, which was defined as being about law, not love.

But Jesus was affirming the primacy of love of God and neighbor from within Judaism, not against it. The great Rabbi Hillel, for one, offered an equivalent teaching. I was raised to think of Jesus as a Christian (or even as a Catholic and judging from Sunday school portraits, a northern European one at that). But Jesus was a Jew, pure and simple.

Here is the foundational irony: In defining itself as the religion of love and justice, the church slandered Jewish religion as legalistic and immoral. The word Pharisee, for example, comes to us as a synonym for hypocrite, yet scholars now tell us that Pharisees were among those with whom Jesus most closely associated. The poet laureate of anti-Judaism was the author of the Gospel of John, the gospel of love. And as we know very well by now, out of gospel anti-Judaism grew the long, wicked legacy of anti-Semitism.

They will know we are Christians by our love? Ask a Jew. Today everyone repudiates gutter anti-Semitism, and the Catholic Church, in the Second Vatican Council's declaration Nostra Aetate, on its relation to non-Christian religions, has renounced its source, which is the "Christ-killer" charge against the Jewish people. Yet that charge is embedded still in the Passion narratives, which are repeated every Holy Week with few attempts by preachers to defuse them.

And so Jewish-Catholic controversies still arise periodically-like the Vatican's apparent approval of Mel Gibson's Passion of the Christ, Pope Benedict's restoration of a Good Friday prayer for Jewish conversion, and his rehabilitation of a Holocaust-denying bishop.

They will know we are Christians by our love? Today go to any large city in Europe and ask a Muslim. The Christian West defined itself against Islam a thousand years ago-and we are still doing it. Islamophobia is the new anti-Semitism.

Are justice and peace what define the church? Even a shallow acquaintance with history tells us that Christians, including Catholics, are not more peace-loving than other people. The Western world was rescued from the religious wars of the 16th and 17th centuries not by Christian teaching about peace but by the Enlightenment and its critique of religion.

Some see Europe today as a secular sinkhole, churches empty, religion spent. Yet, arguably, the greatest act of love and justice in history was the nonviolent resolution of the Cold War. While some of the people who helped that happen were indeed religious-Catholic Solidarity leaders in Poland, Protestant pastors in East Germany, Refusenik Jews in the Soviet Union-the overwhelming majority of the grassroots democracy movements in Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union that accomplished this still underappreciated political miracle were atheists.

It is the generation of Europeans who has walked away from Christian belief that has embraced pacifism, ended the death penalty, and repudiated colonialism and empire. It is in church-going America where violence is still met with even greater violence and where murder is punished by state-sponsored murder.

The church exists for love, peace, and justice? As opposed to whom? What does it do to the Catholic sense of identity to recognize that ideals of love, peace, and justice-however fallen short of-define the heart not just of our religion but of every great religion?

During what German philosopher Karl Jaspers called the "Axial Age," running from 900 B.C.E. to 200 B.C.E., a revolution in human consciousness occurred, what Karen Armstrong calls "the great transformation." This involved Confucianism and Taoism in China, Hinduism and Buddhism in India, philosophical rationalism in Greece, and certainly monotheism among the Hebrews.

All of these religions were built around empathetic concern for the neighbor-by what might be called justice in action. More than that, these religions were generated by the conviction that the ground of being, the transcendent one, the Holy One, God, is only manifest in compassion. To love God, love the neighbor, period.

We Christians associate Jesus with this vision of love as the sacrament of God's presence, yet it is a universal human vision. And such a vision is characteristic not only of religions but of countless communities and institutions that have nothing to do with organized religion. Have you been to a meeting of a 12-step program lately?

How can we Christians affirm ourselves without denigrating someone else? If human experience is itself the revelation of God (we see that in the Axial Age, but we also see it in the Genesis affirmation that the human person is the image of God-the person, not the Jew or Christian or believer), then we must take human experience seriously as such.

The experience of those of us who are of the church involves a certain tradition, tied to a certain person who was himself of a certain tradition. The church is tied to Jesus, who was a Jew, a man at home in the biblical tradition. And that tradition is defined not by triumphal superiority but by the steady renewal of self-criticism represented by the prophets. Indeed, religious self-criticism is assumed by the ongoing act of sacred reinterpretation that is itself the Bible's ultimate source.

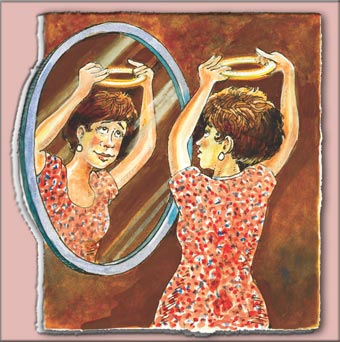

But what makes the church unique if not love and justice? Perhaps we should give more emphasis to another note of our identity-this particular call to reckon with how the church has failed in love and justice, which is why every Catholic Mass begins with an act of repentance. We do this not to denigrate ourselves but to begin with the simple truth. Starting with the ones who abandoned Jesus when he most needed them and with those who then promptly turned his message of love against the Jewish tradition out of which he came-this is who we are.

The first thing to say about the church, therefore, is that we are a people who know we need to be forgiven. The second thing to say is that, in God through Jesus, we know that forgiveness is available.

"Father, forgive them. They know not what they do."

Not "the Jews." Us.

And, of course, such forgiveness is available to everyone. As we honor other traditions for the emphasis on God's open-ended loving mercy-certainly including Judaism but also the other great religions-we see, perhaps, that the search for what makes the church unique is itself beside the point.

Therefore, love and justice are virtues against which we measure our imperfect effort and toward which the experience of being forgiven propels us. The church is the forgiven community, understanding forgiveness as offered to all.

The church exists not to save people but to point to the astonishing good news that the people-all the people-are all already saved. The universality of God's positive regard requires ours.

Out of that knowledge, in humility, the church does its work of peace and justice and love.

This article appeared in the April 2009 issue of U.S. Catholic, Volume 74, Number 4 (pages 34-36).

Add comment