Few writers of the past century have had as big an impact on so many people as Thomas Merton (1915-1968). His readers ranged from popes to high school students, from astronauts to taxi drivers, from mystics to people trying to decide if God exists. His interests were as wide ranging as the Milky Way, from prayer and contemplation to war and peace, from every aspect of Christianity to aspects of Buddhism and other religions.

He was prolific. One of his admirers commented that Merton couldn’t scratch his nose without writing an essay about it. It takes a whole bookcase to hold all the books by Merton. He wrote from the Abbey of Gethsemani in Kentucky, the Trappist monastery he joined at age 25, having converted to Catholicism just a few years earlier while studying at Columbia University.

Because Merton spent most of his adult life in the out-of-the-way monastery, few of his readers had the chance to meet him, but through his books he had friends all over the world.

That was how I first met Merton—by reading one of his books. On Christmas leave from the Navy, while waiting for a bus, I came upon a paperback copy of his autobiography, The Seven Storey Mountain. Though the light in the bus was dim, I quickly found this wasn’t an easy book to put down. I managed to read about 100 pages before I stepped off the bus later that night. In the next few days my main activity was reading Merton. Once finished, I found more Merton to read.

Eighteen months later I was out of the Navy. I had gotten an early discharge as a conscientious objector and become part of the Catholic Worker community in New York. There I found that the leader of the community, Dorothy Day, actually knew Merton.

Over cups of tea she often read aloud letters she had received that day. One afternoon it was a letter from Merton. I was amazed. I knew from his autobiography how he had left the world with a slam of the door to become a monk, and I knew Dorothy Day to be as immersed in the world as the mayor of New York was. Yet, as I came to realize, the two had a great deal in common.

Thanks to Day’s encouragement I sent a letter to Merton. To my astonishment he wrote back. A few letters later he invited me to visit him. Having little money, I traveled by thumb. It took several days to get to far-away Kentucky.

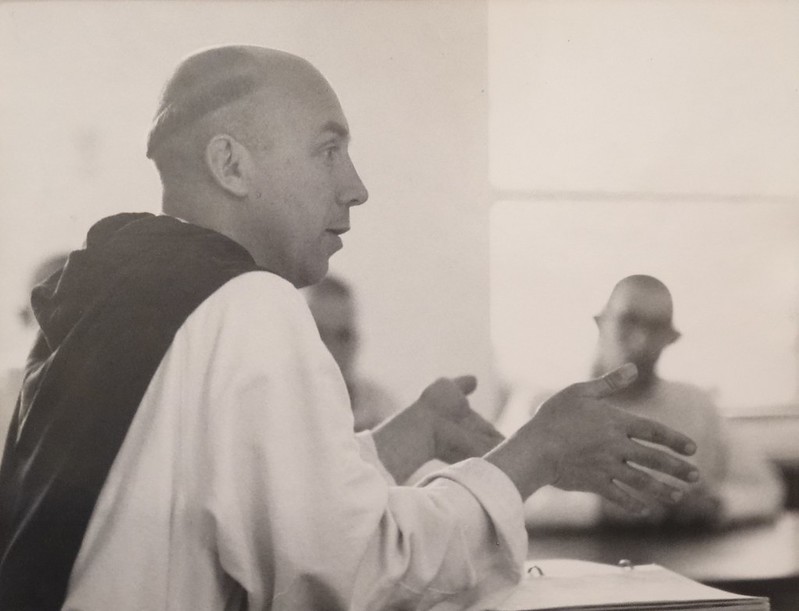

None of Merton’s books had an author photo in those days. The Merton I had imagined hardly resembled the Merton who welcomed me to the monastery. In my imagination he was as lean as a rail, the result of full-time fasting, and not inclined to laughter.

The actual Merton turned out to eat three meals a day and was an astonishingly joyful person. In fact I’d never heard anyone laugh with such abandon. At that first meeting, Merton collapsed on the floor while laughing so hard his face turned red. This was his response to the heady smell of hitchhiker’s feet that hadn’t been washed in three days—“the perfume of the Catholic Worker,” he called it.

That first week together, with hours of conversation each day, laid the foundation for a friendship that lasted seven more years, until his death in December 1968. In fact, it still goes on, as death doesn’t break relationships. While we were to see each other only one more time, we exchanged dozens of letters. For me, he became a mixture of friend, adopted parent, and confessor. I can’t begin to thank him for his unpushy guidance and for his patience with me when patience was needed.

Perhaps the most important thing Merton helped me with was not becoming an anger-driven person—and keeping me from deciding that the church wasn’t quite good enough for me to be part of it. He also didn’t allow me to be swallowed up in ideologies and slogans.

Our letters often had to do with my involvement in peace activities, a work with many frustrations. One letter he wrote has been reprinted many times:

“Do not depend on the hope of results. When you are doing the sort of work you have taken on . . . you may have to face the fact that your work will be apparently worthless and even achieve no result at all, if not perhaps results opposite to what you expect. As you get used to this idea, you start more and more to concentrate not on the results but on the value, the rightness, the truth of the work itself.

“And there too a great deal has to be gone through, as gradually you struggle less and less for an idea and more and more for specific people. The range tends to narrow down, but it gets much more real. In the end, it is the reality of personal relationships that saves everything.”

Image: Flickr cc via Jim Forest

Add comment