“He brought him outside and said, ‘Look toward heaven and count the stars, if you are able to count them.’ Then he said to him, ‘So shall your descendants be.’ ” (Genesis 15:5)

Lent starts this month. But that’s no reason for donning a bleak mood, even though it can seem that way. Since Lent is styled as a penitential time—all purple drapery and fasting and sacrificing—we don’t naturally think of it as a season of hope. Some of us perceive Lent as 40 days of religious dieting. Or a marathon of spiritual practices we can’t wait to cast off after the Easter Vigil. Lent is, in the way some of us approach it, a Catholic bother of a season.

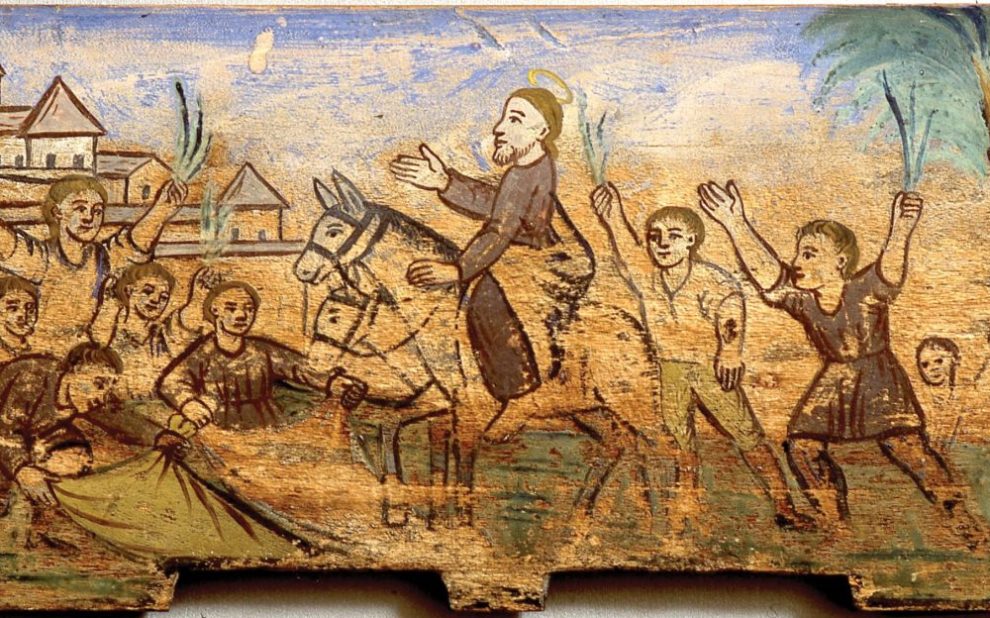

There’s no denying it’s not a carefree time for Jesus. Although the word Lent wasn’t in his vocabulary, Jesus’ final ascent to Jerusalem after his rewarding and fairly serene ministry in Galilee was a sobering change of direction.

Preaching in the countryside to fishers, farmers, and small-town shopkeepers didn’t make Jesus appear much of a threat to either the Romans or the Temple leadership. When he turned his sights on the capital city, however, their complacency turned to alarm. Jesus understood and frequently cautioned his disciples that entering Jerusalem would put him in the crosshairs of very powerful people. It would draw the sort of attention that could turn ugly quickly, not to mention dangerous.

Plenty of folks in Jesus’ Galilean audience were Roman-haters and Temple adversaries. They had no love for Roman collaborator King Herod nor the Judean fat cats who owned the land to which the peasants gave their lifeblood.

Some followers of Jesus, such as Simon the Zealot, were excited at the idea that Jesus might lead an army of followers right through the gates of Jerusalem and into the Temple courts to take command. (Other quasi-messianic leaders would, in fact, half-achieve this scheme not long after the generation of Jesus.) James and John thrilled at the fantasy that they might soon sit on the right and left of Jesus in his coming kingdom. The events that we now call Palm Sunday and the cleansing of the Temple must have made this illusion seem almost within reach.

Given the degree of rage, humiliation, poverty, and frustration people were experiencing in that time in their occupied country, it’s no surprise even the disciples couldn’t really hear Jesus when he talked about being handed over to suffer and die in Jerusalem. It made no sense to go to the very center of power only to surrender all the authority they’d gained. Why risk everything, including their lives, and for what?

What did Jesus hope to achieve in Jerusalem if not a takeover of government or religion or both? Perhaps “hope” was the thing the disciples failed to grasp most of all. Even after years of listening to Jesus and observing his use of authority purely to serve the needs of others, the disciples, like everyone else, couldn’t aim their hope any higher than temporal control.

The only goal they could imagine at the end of this long road was winning some great prize: ridding their land of its hateful occupying forces, installing a new king, or perhaps anointing a new high priest. With their hearts set on winning, the concept of losing, especially losing their lives, was not even on their radar. This made the reality of the crucifixion so shocking, they had to run from the sight, only to huddle in numbness and paralysis.

Hope as Jesus embodies it is a vastly different virtue. Divine hope is the kind that invites our gaze upward, the way Abraham was once invited to look into the sky and count the stars in order to perceive the future God had destined for the nation that would spring from him.

This sort of hope is not simply pie in the sky, nor is it pie on your plate right now. St. Paul says Christian hope doesn’t disappoint but rather gladdens the heart and increases our confidence as bearers of good news.

Our hope, Paul repeats over and over, is in a resurrected Lord—not a Lord who doesn’t suffer and die to begin with. The cross is in the world. All of us will bear it in some form or another. Our hope is not to escape suffering but to overcome it. Our hope is not to avoid death but to be raised to new life.

Loretto Sister Mary Luke Tobin memorably describes how to live faithfully and fully. “Go out on a limb. That’s where the fruit is,” she advises. What Tobin doesn’t say is that crawling out to the thin parts of life will be easy, painless, or safe. Perhaps her time as one of the few female observers at the Second Vatican Council informed her that avoiding the near occasion of peril is not a Christian goal. Convening the Council was a huge risk, yet church leaders of that time seemed to appreciate that risk is where the fruit is.

Tobin spent her later years harvesting that fruit by working toward church renewal, peace and justice, gender equality, disarmament, and protection for farmworkers. She also wrote a book titled Hope Is an Open Door (Abingdon). “I trust that Catholic spirituality of the future will always be characterized by openness,” Tobin writes in what might be described as a refulgence of hope.

Tobin viewed such openness as nothing less than the willingness to entertain the call of the Holy Spirit. The doors she imagined flinging open included an appreciation of creation, ecumenism, Eastern thought, feminist perspectives, the cry of the poor, and our own Catholic mystical tradition. The door to hope is always open, but not all of us are willing to risk passing through it.

Still, how else are we to get to the fruit? This month, our jubilee journey as pilgrims of hope includes recognizing those involved in the world of volunteering (March 8–9) as well as missionaries of mercy (March 28–30). Those who freely give their time and compassion to others have already signaled their willingness to take a chance on hope.

Faith is not possible without hope, as Tobin declared. Believers without hope truly do not believe in much and certainly not in Jesus. How else does Jesus have the courage to turn toward Jerusalem, take up that cup of suffering, and drink it? How else can he crawl out on the limbs of the cross to grasp the fruit of hope in his two broken hands?

Reenvisioning Lent as a season of hope can be challenging. Walking the stations of the cross doesn’t feel very hopeful when we know what awaits Jesus at the end of this devotional tour of sacrificial love in action.

Yet Jesus sees more than the hill of Golgotha as he takes that journey. He lifts his gaze higher, to a heaven full of divine promises as numberless as the stars that once inspired Abraham. Breaking the chokehold of sin and death required first enduring both. The cross is not the end of the road but a door to hope. Jesus doesn’t simply walk to it. He walks through it.

This transforms the meaning of every crucifix we see. The cross is a door, which makes the doorway of hope more than a pleasant metaphor. It makes Lent much more than a Catholic bother of a season, just 40 purply days full of extra fasts, rituals, and collections. Lent isn’t a season we travel in hope of surviving our resolutions and of reaching the grateful end of them. At the end of this season is a door inviting us to more and deeper life.

This article also appears in the March 2025 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 90, No. 3, pages 47-49). Click here to subscribe to the magazine.

Image: Wikimedia Commons

Add comment