“Just offer it up!”

It’s a typical Catholic response to children’s complaints. Bored during Mass? Offer it up to Jesus. Teacher yelled at you? Offer it up. Sick to your tummy? Offer that up, too.

But what if children remain unconvinced? Well, then, tell them stories about the many children who heroically offered everything to God, including their lives.

St. Agnes is a good example. At the end of the third century, Roman officials tortured the 12-year-old girl because she refused to marry; she bravely endured, and God miraculously “preserved her purity,” even though she lost her life. St. Jerome described her as someone who “overcame the weakness of her age.”

About 50 years later, another 12-year-old, a boy named Tarcisius, earned his sainthood when he refused to surrender the Eucharist to a crowd of schoolboys. He was beaten to death, and today he’s a patron saint of altar servers.

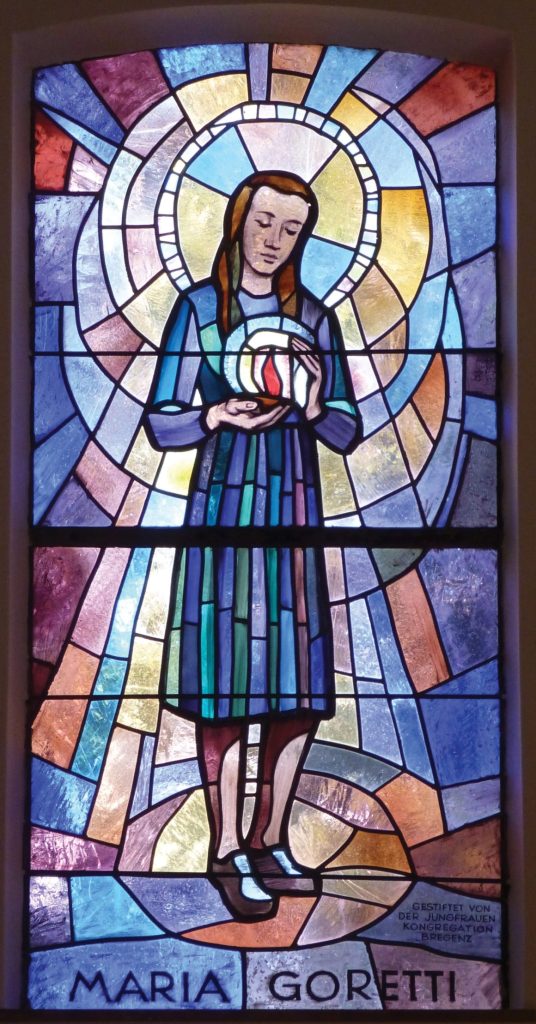

Maria Goretti, at age 11, resisted sexual advances and was then stabbed 14 times. Before she died, she forgave her attacker, who eventually converted to Catholicism. “From Maria’s story,” said Pope Pius XII at her canonization in 1950, “carefree children . . . can learn not to be led astray by attractive pleasures. . . . Instead they can fix their sights on achieving Christian moral perfection, however difficult and hazardous that course may prove.”

The list of holy children is a long one. It begins with the Holy Innocents, the babies Herod killed after the birth of Jesus (St. Augustine referred to them as the “church’s first blossoms”), and it continues on through the centuries, including St. Fina of San Gimignano, who died after “joyfully” suffering a paralytic disease; Blessed Panacea de Muzzi, whose stepmother beat her to death because she preferred prayer to chores (Panacea was 5 at the time); Venerable Antonietta Meo, who, when she was only 6, “cheerfully” endured bone cancer, leg amputation, and death (Antonietta told her mother, “When you feel pain, you have to keep it quiet and offer it to Jesus”); St. Barulas, a nursing child who had his tongue cut out because he refused to deny Christ (his mother encouraged him to die in order to bring glory to them both); and St. Artemas, a child bullied by his teacher and classmates because of his Christianity, who died after being stabbed repeatedly with the classroom’s writing instruments.

The names and details of child martyrs could go on for many pages—countless stories of children who suffered agony with saintly smiles on their face. But are these really the stories we should use to teach children what it means to follow Jesus? All these children suffered and died. Do we want children to think that physical and emotional pain pleases God?

The church refers to many of the little girls as martyrs in defensum castitatis; they died “in defense of chastity.” A few children were granted sainthood because of the “heroic virtue” they demonstrated while dying from diseases. Most of them, however, were martyrs in odium fidei; “hatred of the faith” caused their deaths.

This last justification for martyrdom pitches Christians against a hate-filled and dangerous world. Starting with the slaughter of the Innocents, Jews were often blamed for these tiny martyrs’ deaths (even though Herod was not considered to be truly Jewish). William of Norwich, for example, was supposedly killed by Jews when he was 12; a few years later, 9-year-old Hugh of Lincoln’s death was attributed to the Jewish community; and Benedictine monks blamed Harold of Gloucester’s death on Jewish ritual sacrifice.

No evidence ever connected Jews to these or any other children’s deaths—but, as historian Leah Sinanoglou writes, “Details of the children’s agony became eloquent proof of Jewish enmity and guilt.” Although the church later denied this implication, the shadow lingers at the root of antisemitism. It’s a message of prejudice that the church reinforced when it also blamed Indigenous people for the deaths of other child martyrs.

Unfortunately, children are as susceptible to prejudice as adults. When crusader armies slaughtered thousands of Muslims and Jews in a “just war” they believed would earn them an automatic ticket to heaven, children wanted to join this brave and exciting movement—and so, in 1212, thousands of young people marched off to the Holy Land to kill infidels. Most of the children died or were sold into slavery along the way, but their fervor inspired the Fifth Crusade in 1218.

The Crusades ended, but prejudice against Jews did not. Fourteenth-century Spanish children threw stones at the walls of Jewish quarters during Holy Week while their parents looked on approvingly. Children also took part in many of the antisemitic massacres that raged across Europe, killing tens of thousands of Jews.

When parents use scare tactics to describe marginalized communities, children learn fear and hatred, which often lead to violence. (To see this same dynamic at work today, consider these recent statistics from the FBI: Since 2019, child-on-child LGBTQ+ hate crimes have more than quadrupled in K–12 schools with policies that discriminate against the LGBTQ+ community.)

Through the ages, many Christian parents have seemed blind to the real messages they convey when they offer meek and martyred child saints as role models. In the 19th century, these “edifying” stories gained still more popularity due to the growth of a new genre of literature intended for young people. Not wanting children’s minds to be influenced by the secular world, the church rushed to publish its own books: tales of the child saints, intended to discourage children from sinning.

Today, if you look online, you can still find Catholic parenting sites that advocate teaching these stories to our children. When we do so, our intention may be to affirm the value of surrendering to God’s will. What we “offer up” to God can be transformed into something life-giving, as Christ’s death on the cross demonstrates.

But this may not be the message children receive. Simone de Beauvoir, for instance, who grew up hearing stories about holy children, describes how she and her sister often pretended to be child martyrs. As an adult, in Memoirs of a Dutiful Daughter (HarperCollins), she wonders if “these tales which on the surface were lessons in virtue, resignment, and trust in God were all teaching, by an undercurrent, to seek pleasure in ill-treatment.” She concludes that these stories help create sadists and masochists.

Along the same lines, psychologist Frank T. McAndrew recalls hearing the story of Tarcisius when he was an altar boy. “The message that was received,” he writes, “was that if we played our cards right, we too could be beaten to death by an angry mob and then be admired by others.”

These hidden yet clear messages, says German liberation theologian Dorothee Sölle, direct “our attention to a God who demands the impossible and tortures people.” It leaves children with the impression that to be good, they must meekly obey a deity who rejoices when they are hurt or killed. It tells sexually abused little girls that God would rather they were dead. It discourages abuse victims from speaking out or feeling anger, insisting instead that they forgive the adults who misuse them. It can even contribute to adults justifying child abuse; according to one study, offending clergy often believe God will bestow particular favors on the children they victimize.

Stories about child saints say to children: “Be afraid! The world is dangerous! People want to hurt you. So does God!” These stories also help create a culture where it’s okay to expose children to violence, so long as there’s a moral to the story. As Janet Heimlich writes in Breaking Their Will (Prometheus): “Religion can bring great comfort to children. It can also turn their lives into a living hell.”

Sociologists note that children epitomize human vulnerability. They are “the most marginalized group in all of history,” says John Wall in his book Ethics in Light of Childhood (Georgetown University Press). He goes on to ask what assumptions “make invisible the 10 million children around the planet who die every year of easily preventable diseases and malnutrition?” He points out that this number is equivalent to almost two Holocausts a year and then asks why we tolerate children’s sex trafficking, sweatshops, and soldiering. “Why,” he demands, “do children everywhere enjoy narrower human rights than adults?”

Perhaps in part, it’s because children seem distant from our adult realities, so their concerns can be easily ignored. Whether they’re our own kids clamoring for attention when we’re busy, or children separated from their parents on our borders, or children dying in Gaza and Ukraine, we are sometimes ignorant to children’s realities.

Too often, our church has failed to remind us to rise to children’s defense. Instead, stories of child saints encourage us to become numb to violence against children. We make use of that numbness when we read uncomfortable statistics like these: Around the world, 468 million children now live in areas devastated by armed conflict; 10,000 children die every day from hunger. Perhaps we mentally “offer up to God” these children, trusting in the divine—when what God really wants is for us to take action.

When we describe children’s suffering as holy, ordained by God, are we less likely to work for justice for children? Might we overlook unsafe spaces where children may be harmed? “We must remember,” writes theologian Craig L. Nessan, “to act with [children] and on their behalf, against their suffering and their exploitation, giving them voices to speak out.”

God cares about children—and God came to us a child. In her book Suffer the Children (Paulist Press), Janet Pais writes, “God entrusted Godself to human adults as a human child in the incarnation, and in some sense God continues to entrust Godself to us in every human child.”

Pais goes on to say that how we interact with children “teaches them more about faith than any number of lessons.” We must “remember that the child, every child, is Christ for you”—not because children suffer like Jesus but because they smile and giggle like Jesus, because they play like Jesus, because they love like Jesus.

Instead of celebrating stories of child saints suffering or being brutally murdered, what if we celebrated their lives, honoring their memory? And what if we affirmed the sanctity of all children, in their everyday lives—in all their mischief and fun, grubbiness and beauty? Instead of giving children self-sacrificing maxims such as offer it up, what if we focused on using our faith to empower our children?

“Jesus understands how you feel,” we might say. “He was a child just like you, so he can help you find the answers you need. He never wants anyone to hurt you. He loves you no matter what.”

This article also appears in the September 2024 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 89, No. 9, pages 23-25). Click here to subscribe to the magazine.

Header image: Spencer Collection, The New York Public Library. (1500). Full-page miniature of the Massacre of the Innocents.

All Other images: Wikimedia Commons

Add comment