For our Sounding Board column, U.S. Catholic asks authors to argue one side of a many-sided issue of importance to Catholics around the country. We also invite readers to submit their responses to these opinion essays—whether agreement or disagreement—in the survey that follows. A selection of the survey results appear below, as well as in the November 2024 issue of U.S. Catholic. You can participate in our current survey here.

You never know how long you’ll wait in line for the sacrament of confession. Sometimes you’ll find a line of six or seven people ahead of you, but you’re in the confessional not even 20 minutes later. Other times you’re next in line, but an hour goes by by the time you speak to the priest.

In some of the parishes I’ve been to, I’ve seen a hastily-printed sign taped to a door that reads something to the effect of “Please keep confessions under 10 minutes. If you expect to spend longer, please contact the pastor to schedule an alternate confession time.” I’d imagine the main goal of signs like these is to address the problem I just described–seemingly interminable time spent waiting in the pews for a spot in the confessional to open up. The number of Catholics going to confession regularly has already fallen off a cliff; better not to scare some of the stragglers away by making the experience feel more like a visit to the DMV than spiritual nourishment.

But directives like this have another boon: they invite us to resist the temptation to turn the confessional into the therapist’s couch, a place where you show up and talk through your problems and hopefully, given enough time, get to the heart of just exactly why things keep going wrong.

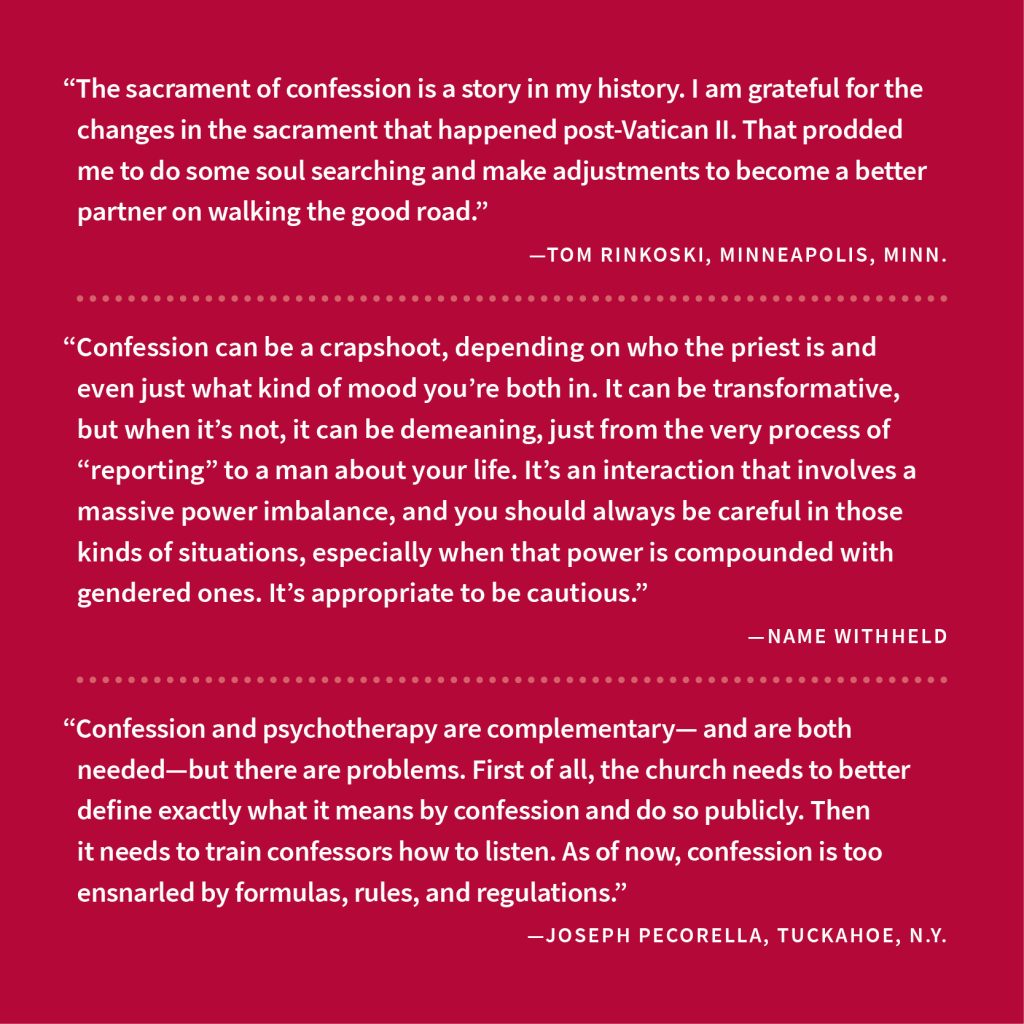

I don’t say this to disparage therapy (or spiritual direction, for that matter), to suggest that confession is better than therapy, or that if you go to confession you don’t need therapy. I’ve seen plenty of Catholics make such claims, and they’re making exactly the same mistake that I’m pushing against here: that confession and therapy are somehow basically the same thing. They are complementary practices, to be sure, but seeing one as interchangeable with the other risks shortchanging both.

Reframing all manner of things through the lens of the therapeutic is having something of a moment right now. It’s hard to go anywhere without seeing words like narcissistic or sociopathic used in places where one could just as easily say self-centered or cruel. There are plenty of times where this kind of reframing is unobjectionable or even good. It might well be beneficial to, for example, repackage things like eating well and making time to rest and do the things you enjoy as self-care.

However, this practice often proves unhelpful and may even cause harm. Take for example the kind of anti-racist advocacy that can end up prioritizing white people examining their own internalized bias and privileges over and above actually making concrete reparations to people of color. Or think of climate advocacy wholly focused on re-examining one’s personal “relationship with the earth,” making no mention of the need for large, global-scale solutions to actually address the problem.

Now of course, you should interrogate your own biases. You should think deeply and critically about your relationship with creation. You should spend time examining yourself and (perhaps with the help of a therapist!) figuring out areas in your own life in need of healing, improvement, or simply better understanding. But focusing all of your energy on these practices is not the way forward: it can quickly become myopic, navel-gazing. Or, to use a therapeutic term, it can become rumination, something most therapists would agree is not good for one’s mental health.

I’ll return to the sacrament of confession by way of reference to “The Twelve Steps” of Alcoholics Anonymous. What one does in therapy or therapy-like settings jives pretty well with Step 4: “Make a searching and fearless moral inventory of oneself.” But confession is far better summed up with Step 5: “Admit to God, to oneself, and to another human being the exact nature of one’s wrongs.”

The confessional is where you begin doing all the things that come after making a personal inventory of your faults and shortcomings. It is not the therapist’s couch: it is the hallway that leads you out of the office and back into your life.

One of the great graces of the sacrament of reconciliation is that it is a school for learning to make a good apology, something which is astonishingly difficult. We all know a good apology when we hear one, but at least speaking for myself, making a good apology can be a struggle. It’s easy to fall into excuse-making, shifting blame, or downplaying the harm you caused. Looking someone in the eyes and simply saying “I have wronged you, I’m sorry, I will do whatever I can to make this right” is an extremely uncomfortable thing to do.

And yet, this is what we are asked to do in confession. The act of contrition makes no room for the kind of rationalizing we may want to use to save face, to protect our fragile egos, or even just to make sense of our own faults: “In choosing to do wrong and in failing to do good, I have sinned against you, whom I should love above all things.” And here’s the upshot: God’s forgiveness will come once you’ve said your piece. That’s not a guarantee you can find just anywhere or with just anyone.

Going to confession trains you, if you let it, to become the kind of person who is good at making apologies, the kind of person who admits their wrongs and makes penance and reparation for them, in a context where you know you’ll get what you came for (if you will). You perform all the actions of an apology––preparing what you’ll say, looking another person in the eyes, forcing those hard words to come out–– but you get to do it with someone who you know will accept it: God.

By becoming the kind of person who not only makes fearless moral inventories but also admits one’s wrongs to God and another human being, you can also become the kind of person who does Step 9: Making direct amends to the people you have harmed. This, I think, is the grace that God is pouring out in the sacrament of reconciliation.

This article also appears in the November 2024 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 89, No. 11, pages 31-35). Click here to subscribe to the magazine.

Image: Unsplash/Annie Spratt

Add comment