Liturgists are sometimes fond of repeating an old theological principle: Lex orandi, lex credendi. Broadly, this means, “The way we pray shapes what we believe.” The more varied one’s experience with differing Christian liturgical traditions, the more this truth is borne out. How we pray not only shapes but also proclaims our understanding of God and of ourselves.

Through her art, Laura James has been shaping Catholic worship in the United States for more than 20 years. In parishes throughout the country, as the opening hymn rings out, a Book of the Gospels (Liturgy Training Publications) is held aloft with Laura James’ imagery proudly emblazoned across its cover. As the Word is proclaimed, her sacred images illuminate its pages. We see Mary joyously greet Elizabeth in a verdant landscape on the Fourth Sunday of Advent. We see red glowing tongues of fire descend upon a diverse group of disciples at Pentecost. Each powerful image is a unique visual proclamation of the gospel and shapes the faith of the local community.

Jesus with the Creatures

Some characteristics of Laura James’ religious imagery are instantly recognizable as belonging within a tradition of Christian sacred art. James’ work draws from the rich heritage of Ethiopian iconography.

Impressively, Christianity in Ethiopia stretches back 1,500 years or more. Ethiopian iconography features characteristically flat figures with large eyes. The figures themselves are culturally specific, revealing a deeper truth about the incarnation: Christ took on our humanity in all its specificity. Or, to put an ecclesial twist on it, as Franciscan Sister of Perpetual Adoration Thea Bowman once said to the U.S. bishops, “The leaders are supposed to look like their folks.”

Thus, Ethiopian icons depict Jesus as Ethiopian, showing a deep solidarity with his people. Bold colors and strong lines guide the viewer’s eyes. James incorporates many of these devices to extraordinary effect.

Consider her painting Jesus with the Creatures. In her Book of the Gospels, this image accompanies a reading from the First Sunday of Lent. Mark 1:12–15 tells of Jesus being led by the Spirit into the desert for 40 days “with the wild beasts.”

In James’ visual telling of this gospel story, Jesus is with the creatures in a peaceful landscape. Only the diminutive snake looks aggressive. The rest of the creatures appear in harmony with Jesus. In fact, their eyes gently gaze upon him in anticipation. One thinks of Psalm 104:27: “These all look to you, to give them their food in due season.”

Here is Jesus the creator and sustainer of creation, ministering to all creatures. James transforms the desert from a desolate land of testing into a thriving ecosystem where Jesus cares for all of God’s creatures.

As Pope Francis reminds us in Laudato Si’ (On Care for Our Common Home), Jesus “was able to invite others to be attentive to the beauty that there is in the world because he himself was in constant touch with nature, lending it an attention full of fondness and wonder.” In Jesus with the Creatures James returns to this important truth.

Jesus Calms the Storm

Creation again takes center stage in Jesus Calms the Storm, an image depicting Mark 4:35–41. Here, deep blue, Vincent Van Gogh-like swirls of wind and waves encircle the crowded boat. The congenial, unperturbed fish contrast sharply with the anxious disciples. Jesus’ calming effect is visually portrayed through the stable and secure boat: It is not disturbed by the tides. It is squarely placed in the middle of the composition, gently rounded and balanced, with symmetrical lines in its hull curving out like strong buttresses against the chaotic surroundings.

Perhaps most intriguing in this painting is James’ depiction of the disciples. They are packed into a huddled mass, terrified by the storm. In a subtle but deliberate choice, James portrays a number of them as faceless. Do they represent all those who feel nameless, overlooked, or lost in the world? Do they represent those whom society marginalizes, whose lives face constant uncertainty? Are they seeking safer shores amid the tempests of life? Whomever they may be, they have faith in Jesus, and he willingly guides them through the storm.

This is a theology of accompaniment: Jesus abandons no one. Instead, he journeys with his followers even through the depths of uncertainty and despair.

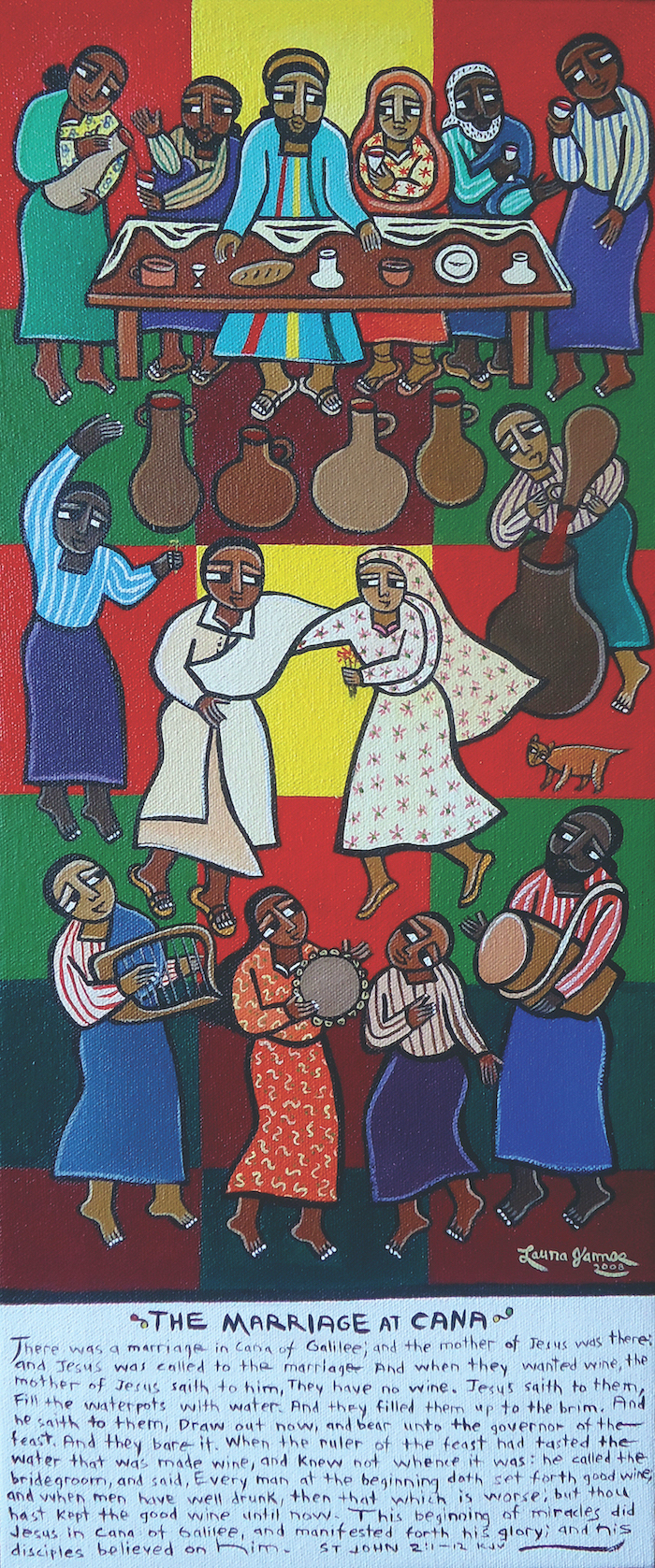

The Marriage at Cana

In her imagining of John 2:1–12, James treats us to a lively, colorful composition titled The Marriage at Cana. Here, a community joyously gathers to sing, dance, and celebrate a newly married couple. Jesus spreads his arms in a gesture of offering. Abundant wine is poured and shared generously. The background colors create a visual rhythm, echoing the festive drum and tambourine. The community’s joy is palpable.

Something more than a wedding may be happening in this rendition. Two bright yellow squares draw our attention to Jesus and Mary at the table and the newlywed couple dancing. These squares not only highlight the figures but also function almost like the heavenly golden background of an icon. Given Jesus’ actions of sharing bread and wine, the joyous banquet, and the diverse gathering, this golden light evokes an eschatological dimension to this celebration. It can be seen as an in-breaking of the kingdom of God in the historical present.

Considering the beautifully diverse gathering of people, perhaps womanist theologian Diana Hayes’ evocative term kin-dom more aptly describes this celebration. It’s a vision of a community uniting as children of God and building sacramental bonds. It’s a vision that reminds us of who we are and what we are working for. It’s a glimpse of heaven in the here and now.

A Sermon for Our Ancestors

Visions of a joyous future do not erase suffering, diminish the past, or minimize current struggles. Thirty years ago Sister Thea Bowman confronted the U.S. bishops with the experience of being a black Catholic in the United States. She sang, “Sometimes I feel like a motherless child, a long way from home.” She then powerfully inquired, “Can you hear me, church? Will you help me, church?”

Today Bowman has been named a servant of God, and her cause is up for canonization. Her question, however, is sadly just as relevant as it was 30 years ago.

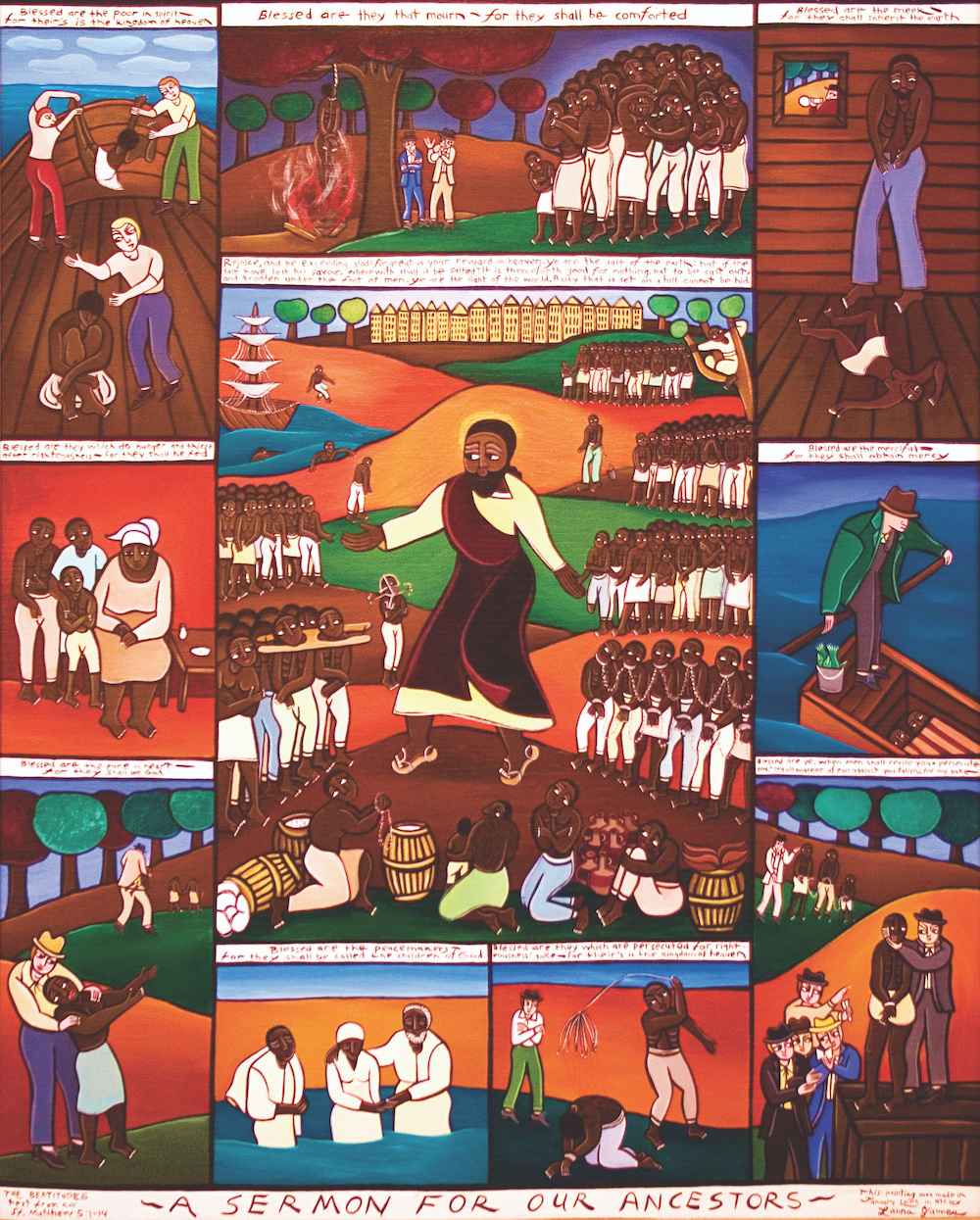

A Sermon for Our Ancestors is equally a sermon for us. Divided into 10 panels, the image documents a history of violence, racism, and oppression. It draws into question the value of Christianity’s impact in this country.

Each panel portrays an atrocity that is then contrasted with one of the Beatitudes from Matthew 5:1–14. A white man tears a black child from the arms of his mother as we are reminded,

“Blessed are the pure of heart, for they shall see God.” A black woman is thrown off a boat by white men to drown under the inscription, “Blessed are the poor in spirit, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven.”

The oppressors in this work are clearly not followers of Christ, and there is little salvation in this world for the oppressed.

Jesus, centrally placed atop a hill, rises tall above multitudes of enslaved people looking to him for salvation. He reaches out to take their hands. This does not end their suffering but shows that he is one of them. He tells them in the inscription, “Ye are the light of the world. A city on a hill cannot be hid.”

The painting itself is a testimony that the history of slavery will not be hid. The image is a refusal to be silenced and a challenging sermon for today.

Ruth

Benedictine Sister Joan Chittister opens her wonderful book The Story of Ruth (Eerdmans Books for Young Readers) with the simple but important observation: “The Book of Ruth is a woman’s story about a woman’s life.” Its inclusion in the biblical canon is all the more remarkable given the patriarchal context. Yet, as Chittister emphasizes, its vision of flourishing is for women and men alike. The story of Ruth and her mother-in-law, Naomi, presents not only women supporting each other in reaching fullness of life but also drawing out the best of those around them despite challenging circumstances.

In her painting Ruth, James celebrates these amazing women. She doesn’t depict the loss of their husbands, their poverty, or their lack of security in a distant land. Instead, we see the moment Ruth’s industriousness and Naomi’s wisdom come together to forge a new future.

Ruth’s hard work has yielded abundant food. Her basket of grain is overflowing and ready to be shared. The world is in bloom, wreathing her with flowers and branches. She powerfully rises above her surroundings. Her hair swung back, her feet in motion, she is moving forward. She is becoming fully herself, and God and all creation celebrate her.

The sacred art of Laura James challenges and inspires. Her compositions are filled with people navigating the difficult task of reaching fullness of life within a community.

Doesn’t that also describe us as we gather in church on Sundays? Isn’t this also our hope and our prayer?

This article also appears in the May 2020 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 85, No. 5, pages (10-15). Click here to subscribe to the magazine.

Image: John Zich/ZRIMAGES.com

Add comment