Because I did not take my husband’s last name when we married, my self introduction always includes an apology and an explanation. The apology is not explicit. It is the slightest sweep under the rug. You don’t even see my broom and I often don’t even realize I’m holding it.

When I introduce myself to a classroom of students, I say, “It’s Ms. Rose, but I’m married. I didn’t take my husband’s name. I love being married to him. It’s a choice we made together.”

The same sort of tumbled apology/explanation comes out when correcting someone who has called me Mrs. Levan, the last name of both my husband and our children (also our mutual choice). “It’s Molly Rose, actually. I didn’t take my husband’s last name, but they’re all mine.”

All of this is fine. I recognize the need for clarification, but I’d like to stop apologizing.

In many ways, my husband and I enjoy a traditional marriage. Currently, he is the breadwinner and I am our children’s main caregiver. I’m pretty sure he has never cleaned the bathrooms while I am considerably less likely to mow the lawn or take out the garbage. We are a Catholic family with active Catholic values, but we both cringe a little at the word traditional, with all its limitations and trappings.

Before I get into the tradition of name changing, a brief explanation into our choice for keeping my maiden name. I was 33 when we married. I could argue that I had too solidly established my self identity at the time, but that’s not true. I fully believe that two became one on our wedding day, and my self identity has gone through serious upheaval since becoming a wife and a mother. While that evolution has sometimes been painful, I have loved every part of it.

I could also argue that as a writer, I wanted to retain my own name for the sake of my professional life. While there’s a case to be made there, that’s not really why either.

I could say that Rose is a pretty name and I didn’t want to leave it behind. There is some truth to that, but not enough to have left my husband’s surname off the end of mine.

I didn’t change my name because it didn’t feel right and it didn’t represent the marriage my husband and I wanted for each other. Leading up to our wedding, I didn’t do any research into the tradition of taking a husband’s last name or into the politically charged reasons for refusing it. My husband and I talked about it; I asked him all sorts of questions about manhood and patriarchal predispositions, but when it came down to it, it didn’t feel right to him either. My husband fell in love with Molly Rose. Why not keep her around?

My father is the biggest opponent to our choice not to change my name, which is ironic since it is to his name I cling. If I receive mail from him, it comes to Molly Levan. That’s fine. It doesn’t bother me because I know who I am and I like receiving packages in the mail no matter who they are addressed to. It’s the reasoning behind my dad’s thinking that bothers me and it comes down to one problematic word: tradition.

When I push my dad on why he thinks I should change my name, he brings up the usual arguments: family unity and confusion for the children who don’t share my last name. These are both decent arguments, but I counter them by saying that as academics with atypical schedules, we share more hours at home building family unity than most. And as to the confusion for my children, there is none. Our names are still Mom and Dad.

But his last argument, the one that really irks me is when he says, “Because it’s tradition. That’s why.”

Tradition as an excuse for changing a name is not universal. Chinese, Korean, Italian, and Greek women do not change their names. In fact, the 1789 Revolution in France disallowed anyone from using any other name than the one on their birth certificate. The same goes for women in Québec, the Netherlands, and Belgium. There is no biblical precedent for taking a man’s name; most people back then did not even have last names. So the blanket argument of tradition clearly does not hold up well.

In America, the tradition of a woman taking her husband’s name stems from the now extinct doctrine of Coverture, which understands a woman as the property of her husband. This custom identified marriage as a contract wherein a woman is transferred from her father to her husband, like a cow or a credenza or a cottage home by the lake.

At age 33, I didn’t need transferring. Nor did I need it at 18 or 21 or 29. I chose my husband. He chose me. But before that, God chose us for each other. Some days I am a better partner than others, but I’m afraid I would never make very good property.

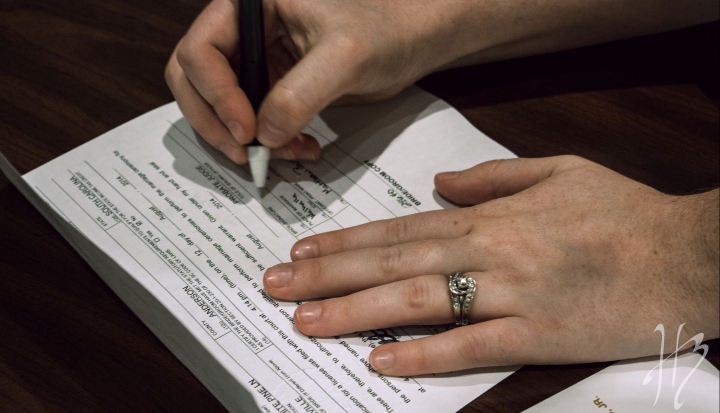

Our choice did not involve any hyphenation or amalgam of each other’s last names because that didn’t interest us. Our children have my husband’s last name. After open communication and prayerful consideration, these are the choices we made together. They are the right choices for us.

Often when I introduce myself and my children, there is that moment, that skipped beat, when I can see people doing the math on our names and our genetics. There is no mistaking the shared DNA between me and my children. And despite my husband’s constant presence and fully shared parental duties, our son and daughter are a hardcore Mama’s Boy and Mama’s Girl. The fact that my last name is different than theirs has no bearing on my role as mother or wife.

I have many things to apologize for in life, but keeping my maiden name is not one of them. I am not sweeping my choice under the rug anymore. I’m putting the broom down, but I’m still happy to discuss our choice. You can even send your letters to Molly Levan. It doesn’t bother me at all because my husband and I are certain of who we are and who I am. It’s not that words and names don’t matter. It’s that they do.

Molly Jo Rose’s column, In and Of the World, focuses on finding God’s goodness in the darkest places of the world.

Image: Flickr cc via Heather Bodine.