Whether school uniforms, habits, or vestments, Catholics are easily distinguishable by what they wear.

It’s easy to assume that such highly visible markers of faith have always been the same. And yet, says Sally Dwyer-McNulty, a professor of history at Marist College, this couldn’t be further from the truth.

Dwyer-McNulty became interested in Catholic clothing while working on her dissertation about Catholic women in the period between World War I and the Second Vatican Council. Researching Catholic education during this era, she happened to be examining some yearbooks from the first diocesan Catholic high school for women in the United States. “Something struck me as odd,” she says. “The girls in the pictures weren’t wearing uniforms. Until suddenly, in 1924, they were.”

At the time, Dwyer-McNulty says, it didn’t have much to do with her dissertation, so she just tucked the observation away. But she began to pay more attention to images of Catholics. “One time I saw an image of a priest, and he wasn’t wearing a Roman collar,” she says. “And I thought, ‘Why did I assume that he should be?’ ”

Over time, these observations led her to write an entire book on the subject. Common Threads looks at the development of Catholic clothing from the 19th and 20th centuries and how what Catholics wore said a lot about who they were and what they believed.

Why is clothing so important in American Catholicism?

Clothing is definitely one of the more significant aspects of the Catholic symbolic repertoire. It’s associated with liturgy, status, and people’s relationship to material objects. It helps define the religious body, or the leadership of the Catholic Church, and how people have muted their individualism in their commitment to the church. It has conveyed a sense of community, solidarity, and allegiance.

It can also be a way of communicating to non-Catholics. Take a priest in a Roman collar, for example. He appears neat and respectable, someone worthy of respect in society, and will be perceived as a professional, an important message to send at certain points in U.S. history when Catholics were not always well accepted. Likewise, women religious were often considered unusual. But if they were seen doing charitable work in their distinctive clothing, it helped win respect from non-Catholics.

We think of Catholic clothing—whether a priest’s vestments, school uniforms, or religious habits—as being fairly universal and unchanging. Is this really the case?

Clothing has changed pretty drastically over time for a variety of reasons. First, the United States was considered a mission territory until the beginning of the 20th century. When Catholics—whether priests, monks, or women religious—move into an area where the church is not well established, there was some flexibility regarding certain church regulations, including in appearance. Catholics wore clothing that would win the acceptance of the people. Not looking too distinctive allowed priests and women religious, especially, to acclimate to the area. As a result, there was no “standard” Catholic clothing in the United States for a long period of time.

Other times, changes in “uniform” were due to more practical reasons. The habits of women religious, for example, often go back to the 16th or 17th century, to the foundresses of their order. They became a symbol of antimodernism. But while they may not have changed very much, they did change.

Communities of women religious often adopted whatever widows wore during a specific period. Widows would often wear dark hues or a black garment to avoid attracting attention, and this seemed like a good model for women religious, who were supposed to be dead to the world and to reject vanity. Over time, this clothing became codified in communities’ constitutions, which laid out the rules of the habit and were voted on by the community.

However, when women moved to different parts of the country or to the United States, there were sometimes changes based on access to fabric. Or sometimes something sent in the mail from Europe would become bent, so the entire community started wearing it bent.

In the 1950s, women religious started driving. And depending on their headpiece, sometimes their peripheral vision was compromised by their habit. So that led to more changes. They became mindful of being able to do their work safely. If going out in a habit meant they would be more likely to be attacked in some areas, then they wouldn’t go out in a habit. (The opposite was true as well: Often women would wear habits while working in the community to keep them safe in dangerous areas.)

And, of course, the clothing of women religious changed still more drastically after the Second Vatican Council, when many communities stopped wearing habits altogether. As a result, women religious could rethink what it meant to have an appropriate feminine role and demeanor, especially within the context of the growing feminist and civil rights movements of the time. They were able to reevaluate their vocation as independent-minded women who had chosen to live in religious community.

Many of these women were already very active in their neighborhoods and dioceses, but they remained separate because of their habits. Wearing lay clothes allowed them to develop a new sense of themselves as leaders, educators, administrators of hospitals, and social workers.

Mother Marianne Cope (1838–1918). The habits of women religious were often based on widows’ clothing. Meant to be dark and unobtrusive, they signaled that women religious had rejected vanity in service to their vocation. Wikimedia Commons.

What about Catholic school uniforms? How did those develop over time?

The first Catholic uniforms for children were in institutions run by Catholic orders, such as asylums. They often had a required dress that was both a form of instruction or discipline for the children and a judgment in a way, a remark on the parents’ moral failings, whose behavior led to their children being in an asylum.

At the same time, selective Catholic girls’ schools often had dress codes. Students were required to bring a certain number of dark dresses, aprons—white for younger students, dark for older students—a white suit and gloves, things such as that. But there was no strict uniform.

A student might receive a swatch

of fabric in the mail to take to her tailor to ensure her clothing would be the

right color or made out of the right material. But there wasn’t a store where a family could go to purchase their daughter’s uniform.

Having this dress code helped distinguish girls who went to convent schools and academies from less selective Catholic schools or public schools. The clothing also wasn’t that far from the sisters’ own appearance.

Eventually, when the dioceses got involved in Catholic education, the sisters who had taught in asylums or in select girls’ schools became teachers in these much larger Catholic school systems. And they brought the idea of religious uniforms or dress codes with them. But the uniforms in these new schools looked different from those at earlier institutions.

Around the same time, in the early- to mid-1920s, ready-made clothes were becoming available. Soon there were businesses that specialized in making Catholic school uniforms. This happened piecemeal throughout the country, but eventually uniforms became a recognizable symbol of Catholic school students.

Recently there has been an increase in independent Catholic schools where the majority of students may not be Catholic. And yet these students are still wearing Catholic school uniforms. This very visible symbol of Catholic identity is being worn not necessarily by members of the Catholic Church but by people who value some of the Catholic traditions and values. In this way, these uniforms have come to symbolize educational values more than theological ones.

How did we get from early dress codes to what we think of as the universal Catholic uniform today?

As Catholic schools became more widespread, schools would market themselves through their uniforms. Different schools within the diocese, for example, would have different colored uniforms in the same cut. Girls would often wear a pleated wool skirt, blazer, blouse, beanie hat, knee socks, and saddle shoes in whatever the color of their school was.

The cut of today’s Catholic uniform, at least for girls, stems from the 1920s. It’s this boxy style that consists of a middy blouse and jumper. But the plaid, which today we take for granted as part of the Catholic school uniform, is a later addition and seemed to arise in the 1950s.

While I was researching this book, I interviewed a uniform maker named George Bendinger who is credited with starting the plaid uniform, at least in Philadelphia. Philadelphia was home to the first diocesan high school and one of the early promoters of Catholic school uniforms. And in the 1950s Bendinger started supplying these plaid uniforms to students that were somewhat “Celtified,” or that associated Catholicism with an Irish Celtic heritage.

What about boys’ uniforms?

While Catholic school uniforms started at select Catholic girls’ schools, there were also dress codes for Catholic schoolboys, although they were much less strict: They had to wear a jacket, a tie, a pair of trousers, and a button-up shirt. After World War II, the uniforms became more standard. Everyone started wearing the same jacket, the same color tie and trousers. This was partly because of the cultural milieu: There was a societal focus on patriotism and militarism during the Cold War, and Catholic schools responded by making their uniforms more consistent and distinctive.

Sister M. Luigia’s fifth-grade class, St. Mary Magdalen de Pazzi Grade School, 1960. Boys’ uniforms in the mid-20th century were often less strict than girls’. While they might have to wear slacks, a button-up shirt, and tie, there were often no requirements about color or style. This began to change during the Cold War, when Catholic schools responded to the rise in militarism and patriotism by making their uniforms more consistent and distinctive. Flickr cc via Jim, the Photographer.

Was there an economic reasoning behind uniforms as well?

Originally, requiring uniforms was more economical. A family would purchase a uniform for their daughter, who would wear it for four years and eventually pass it down to a sister. A family would have to make an initial investment, but then they didn’t have to worry about having a variety of clothing for their children.

During the Great Depression, this was something families were concerned about. If you read letters to Eleanor Roosevelt, people often asked her for hand-me-down clothes or money for clothing. People would forgo going to school if they didn’t have a presentable dress or a serviceable pair of shoes. Having a uniform that lasted, therefore, was a significant cost saving.

At other times, the uniform created a type of Catholic consumerism. Early elite schools were able to differentiate themselves by telling students, “We expect you to bring a certain number of outfits that look this particular way.” Only a family that could afford two dresses in the same dark color with six replaceable collars and cuffs would even be able to apply to the school.

Then, after World War II, when the economy was expanding, dioceses also began to have uniforms that weren’t just intended to save money. Instead, they were meant to be a symbol of Catholic respectability. Students were expected to take pride in their uniforms and wear them a particular way. As a result, dioceses began feeling comfortable making more demands on families: They required students to wear a blazer or for girls to wear a beanie or gloves to school.

This economic comfort also resulted in schools’ changing uniforms. Sometimes there would be a distinctive uniform just for seniors. Students liked this because they were set apart and no longer confused with underclass students, but it was an added expense for families.

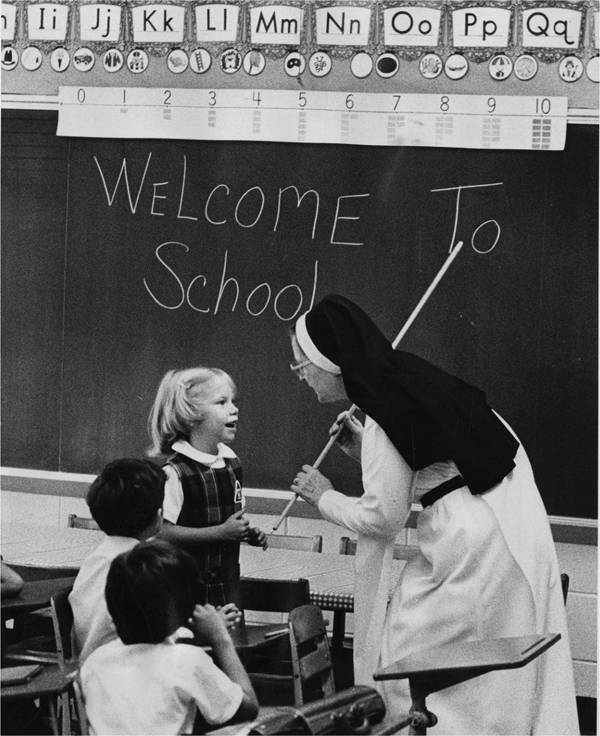

Erica Wurster introduces herself to Sister M. Anastasia. Catholic school uniforms consisting of a blouse and jumper stem from 1920s fashions. The plaid is a later addition to the uniform and became popular in the 1950s. Courtesy of the Special Collections Research Center, Temple University Libraries, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

How was clothing used to illustrate a specific model of Catholic femininity?

There is this idea in some strands of Catholic teaching that a woman is prone to vanity and should be concerned with modesty. So there has been an emphasis on women being covered in a particular way and on adhering to a specific idea of femininity, typically by wearing a dress. Often modest and feminine dress was associated with what Mary would want or wear.

Women were taught to avoid clothing that offended God. In 1928 Pope Pius XI denounced the dangers of immodest dress and gave specific guidelines for women’s clothing: Necklines could be no more than two inches below the hollow of the neck, sleeves must be halfway to the elbow, skirts had to reach below the knee, and stockings couldn’t be flesh-colored. He also gave guidelines for bridal gowns. He was very concerned about immodesty.

In the 1930s Cardinal Mundelein in Chicago started the League of Modesty. In the 1950s there was a Purity Crusade, which encouraged women to wear clothing Mary would wear if she were a young woman.

All of this suggested that women needed guidelines. They couldn’t decide or make good choices on their own; they were particularly weak vessels when it came to resisting vanity. Their need for looking pretty and wanting material things should be corralled or guided. In this sense, Catholic clothing became a statement about the church’s views on women.

Two students receive awards at Camden Catholic High School in New Jersey in 1965. Over time, uniforms became a symbol of Catholic respectability. Courtesy of the Special Collections Research Center, Temple University Libraries, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Is clothing as important in U.S. Catholic culture today as it was in the early 20th century?

Yes, clothing and discussions about clothing continue to be an important part of Catholic culture. For example, in response to Vatican II several orders of women religious decided to move away from their distinctive clothing. But today the religious orders gaining the most recruits are those that maintain the traditional habit. Clothing has become this readily available symbol of tradition and of Catholic identity that is appealing to a lot of young Catholics who are joining orders.

The continued awareness of popes’ clothing choices also signifies the importance of clothing in Catholicism. Pope John Paul II, for example, made statements about being visually present. He seemed to reemphasize the significance of habits, vestments, and other visual symbols. As a result, he was highly visible, particularly at public Masses. Pope Francis, meanwhile, has maintained a very simple appearance that has often been contrasted with that of Pope Benedict XVI.

This article also appears in the July 2019 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 84, No. 7, pages 26–31).

Image: Flickr cc via Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Boston

Add comment