Francis and Clare. Even though he was the better known of the two, it was Clare who most captured my attention at my Franciscan high school. From the beginning, there was something about her life that resonated deep in my being.

Hers was the story of a young woman inspired by a charismatic troubadour, refusing a marriage arranged by her family, stealing away to join the fledgling Franciscan movement as the lone woman in the group, and renouncing all to follow her ideals. This drama had just the right mix of romantic intrigue and spiritual idealism to draw me in. Allowing “Lady Clare” to emerge from the confines of the 13th century in which she lived and speak her vision as clearly today as she did then has been an unfolding journey for me.

Clare. Chiara. The clear one. As her name suggests, Clare had clarity of purpose and intense determination from an early age. She was probably no more than 17 or 18 when she first heard Francis of Assisi preach. Yet, as he spoke, she heard her own voice. In befriending him, she became truer to herself.

As her name suggests, Clare had clarity of purpose and intense determination from an early age.

Clare was born in 1193 to a well-to-do family in Assisi. The patriarchal structures of the times dictated the place of women. Those, like Clare, who felt called to live a life of vowed poverty, chastity, and obedience were bound to live in an enclosure.

Clare didn’t question this. She had other causes that consumed her. And so it was in the little dwelling at San Damiano in Assisi that Clare lived for 42 years until her death in 1253.

During this time, Clare became convinced that a life of radical poverty was essential for maintaining loving relationships among the sisters in the community and experiencing total reliance upon and union with God.

Knowing that formal papal approval was the only way her Rule could survive through the ages, Clare pressed Pope Innocent IV until he acquiesed. Two days later, her mission accomplished, Clare died.

It wasn’t until I visited Assisi that I really met Clare and began to feel her wisdom. I sat in silence at her place at the wooden table in the little cloister at San Damiano. I walked in the garden where she would have prayed, my own steps tracing those she and Francis made 800 years earlier. I climbed the rough-hewn stairs to the dark, attic-like dormitory where she slept among her sisters. It was such a poor life, but something about it felt so rich.

I have always wrestled with my vow of poverty, more so than any of the other vows. My life in the 21st century, though Franciscan, is a far cry from the radical poverty of Clare and her sisters in that little enclave of Assisi.

It was such a poor life, but something about it felt so rich.

There I realized that Clare’s wisdom was not about copying someone else’s vision—even Clare did not mirror the vision of her dearest friend and soul mate, Francis. He was always more concerned about obedience than poverty. We each deal with our own times and our own reality, I realized in Assisi.

Part of Clare’s radical poverty was not poverty for its own sake but for the deeper relationships it made possible. Freedom for relationships—this was her wisdom. She understood that pure relationships, uncluttered by anything that would hold back total and sacrificial loving, must be her vow.

Clare’s message for us is clear, simple and strong: A relentless pursuit of material goods can stifle a heart for compassion. A life preoccupied with acquisitions leaves little space for the kind of longing that only God can fill. The things of greatest value are found not in shopping malls, but in relationships—in deep human connections where loving thoughts replace petty jealousies, and forgiveness heals resentments that have been nursed far too long. We cannot purchase sunsets and stars, yet these are among the richest creations of a holy God. Friends, Clare knew, are the most precious gift of all.

Clare’s message for us is clear, simple and strong: A relentless pursuit of material goods can stifle a heart for compassion.

While Clare lived in a cloister, her voice soared beyond the convent walls. This relentless sage made demands that may have annoyed church leaders. Hers was not a stubbornness born of self-will, but a clear conviction that the way of life she started must be protected.

I cannot help but wonder how Clare would have lived these convictions today. Perhaps she would have entered a convent, perhaps not. I can see her as a lobbyist who presses Congress for health care for the poor. I can picture her as a mother who insists that her children share, be kind, and plant a garden. Perhaps she would have been a theologian, lecturing about prayer from within the wellspring of her own deep spiritual life.

I can even imagine her doing what she did in the 13th century—pestering popes to take women more seriously.

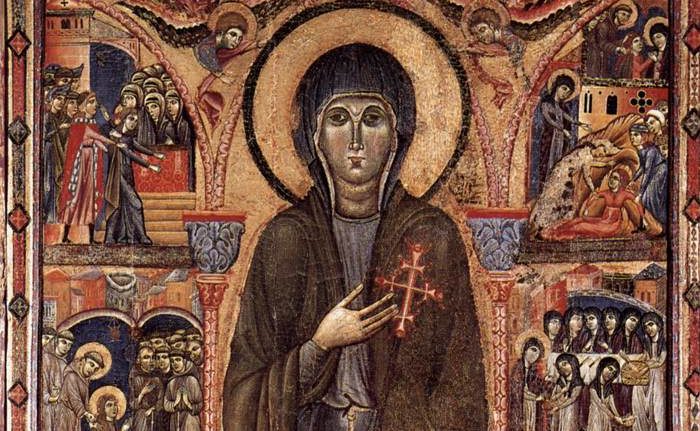

Image: Altarpiece of St. Clare, Basilica di Santa Chiara via Wikimedia Commons

Add comment