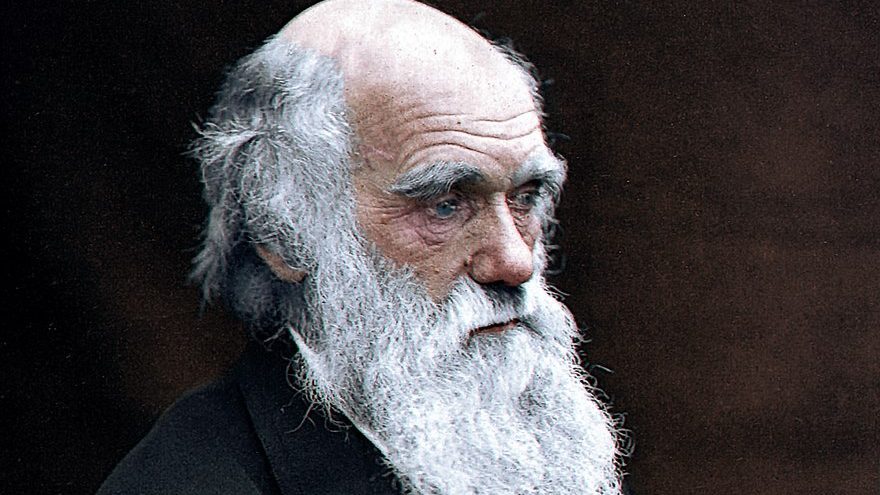

When Charles Darwin was born 200 years ago this month, no one could have guessed the impact his Origin of Species (1859) would have not only on science but on religion as well.

“The name Darwin symbolizes a massive transition of our self-understanding,” Boston College Professor Stephen Pope said in a recent talk at Dominican University in River Forest, Illinois. “Instead of descended from a primal couple specially created by God about 10,000 years ago, we now regard our species as the product of an evolutionary stream of life that has been running at least 4 billion years.”

But for many Catholics, science and faith are often competitors, and sometimes even official church teaching doesn’t do enough to bring them together.

“There’s a way of talking about the doctrines of the Christian faith without treating Adam and Eve as historical figures,” Pope says. “But right now we have a parallel theology, with official statements that endorse evolution but a Catechism that completely ignores it.”

Still, Pope says, final responsibility rests with individual Catholics to integrate faith and science for themselves. “We all have an obligation to deepen in our faith,” he says. “I’m not saying everybody should be a Darwinian or a theologian, but I think there is a call to take faith more seriously and become more reflective people.”

Why should Catholics be interested in Charles Darwin?

Darwin’s theories of how life evolves provide the most powerful and persuasive explanation right now of how human beings appeared on the scene. I think Catholics should read Darwin to understand who we are in our biological nature, including some of the capacities that we have for responding to God in our lives.

But more than 40 percent of the American public believes that humanity is just 10,000 years old as a species, and you have to figure at least a quarter of them are Roman Catholic. A recent poll found that 79 percent of Catholics in Florida would vote not to teach evolution in the classroom.

This is despite the fact that Pope John Paul II officially acknowledged that “evolution is more than a hypothesis.” Pope Benedict XVI has dismissed the debate over evolution as “an absurdity” that flies in the face of “much scientific proof in favor of evolution, which appears as a reality that we must see and which enriches our understanding of life and being as such.”

But beyond evolution’s scientific validity, Catholics regard the world theologically as a sacramental expression of God’s love. The world itself is a symbol of God’s grace, God’s goodness. It’s our habitat, and through it we are given the opportunity to move toward God. So it’s important we understand how creation functions.

Do you think Catholics have integrated evolution into their understanding of the faith?

Catholics, like Christians generally, tend to compartmentalize their world into their professional life, their church, their golf game, and we don’t often make connections between those things.

Darwin asks us to put together all the different parts of our lives and think about how we’re connected to other people as members of the same species. He asks us to look back to discover where we come from. He asks us to look at ourselves now as members of a species that is growing rapidly and doing serious damage to the planet because we don’t live responsibly. And he asks us to look forward, because if we’re not responsible in the future, the human race is going to be harmed and possibly eradicated if environmental catastrophes pile up.

Evolutionary theory and Christianity have often had a tense relationship. How have believers responded to Darwin?

There are a number of different approaches Christians have taken to evolution. The first, the strategy of rejection, tends to insist that religion is our primary authority, and information about evolution is either irrelevant or a threat. Biblical fundamentalists, of course, reject evolution outright. If the Genesis accounts of creation are not historically accurate, they fear, then revelation is not true. In such a case God is not the author of the Bible because God only reveals truth.

The second position, avoidance, is more common with Catholics. This approach says evolution might be right, but I’m not going to trouble myself with it. It is sometimes rooted in the notion that biology is for scientists only: I know I’ve got genes, let’s move on.

What’s wrong with that?

Avoidance for people who are really busy is sometimes a necessary evil. But it’s bad if it becomes an untouchable policy for people who have the freedom to be more thoughtful.

I think the strategy of avoidance is actually kind of scandalous. It’s obviously absurd to have so many Catholics not believing in evolution, and it’s a scandal to educated people who as a result think Christian faith is childish. Some believers are giving the impression that you have to choose between being intelligent and educated or being faithful. You don’t, and in fact reason and faith go together. One reinforces the other.

At the same time, it is confusing to find papal talks and authoritative church documents, including the Catechism, continue to speak of Adam and Eve as real historical figures, of the Garden of Eden as a place in which a serpent talked to the woman, and of a historic expulsion from paradise.

So reasonable people of faith should embrace Darwin?

That’s the appeal of the third strategy, partnership. Theologically some Christians embrace an evolutionary vision of life as forward-looking, open, innovative, and creative. Rather than static, the world is always a process involving adaptation and change. Evolution becomes the main paradigm for thinking about the world, and Darwin seems to be the ally of those who believe that reason, particularly in the intellectual form of science and in the political form of democracy, which together provide the basis for modern progress.

But there’s a moral danger in this approach of not having any sense of limits, such as with genetic engineering and other forms of biotechnology. An uncritical embrace of Darwinian evolution and modern, technologically-driven progress—one that says that we have to take over the reins of evolution itself and direct it where we want to go—runs the twin dangers of both radically diluting Christian identity and of losing a sense of the morally appropriate limits to technology.

Is there a better way of talking about faith and evolution at the same time?

I refer to it as “critical appropriation,” trying to take the insights from Darwin’s theory to enrich faith rather than diminish it. Theologically I describe the response as evolutionary theism, the view that evolution is God’s way of making the world.

That’s opposed to two positions. Creationism says that God made the world as it is described in the first chapter of Genesis; the way Darwin explains it is false. The alternative extreme is the naturalistic view, that evolution was the result of a totally unintentional big bang that just happened for no apparent reason.

How is God involved in the evolutionary process?

First, God affects the course of nature by being the cause of everything that exists at any time. Second, God creates the conditions that lead to the universe, to the galaxies, to the evolution of life.

Third, since nature’s law-like regularities are attributable to God, God is the author of what some theologians and scientists call “emergent complexity.” Over time certain kinds of organisms are going to evolve that then provide the context for certain more developed organisms to evolve, eventually leading to intelligence and love. In that sense, the laws of nature are structured to give rise to intelligent and loving beings that are able to love God and neighbor.

But what about God’s personal care and love for the world?

We also have to talk about God’s providence. Providence is how God’s power and love interact with the contingent events in nature and history to shape things for the greater good. God’s providence is not subject to scientific study.

Christian life is really a response to God’s providence. It is made concrete in individual actions, but it also works in collective settings. We can talk about the U.S. civil rights movement as being an expression of God’s providence, or the peace movement in Northern Ireland. Wherever we see goodness emerge out of evil, I think we can reasonably say it is God’s providence.

That’s not to say that providence is always like winning the Super Bowl—it’s over and we won, mission accomplished. It’s complex, but we have to take providence into account when we talk about God working through nature and history.

How does the evolutionary worldview address suffering and evil?

Darwin himself was raised as a conventional Anglican but gradually became either a deist or an agnostic. He eventually found it impossible to affirm the traditional doctrines of divine goodness, omnipotence, and providence in light of a natural world rife with pain, predation, waste, and suffering.

God our Father might count all the hairs on our heads, but what does that mean? God cares but does not intervene to stop the continual slaughter of the innocents?

In fact, for many neo-Darwinians Christians are irrational in placing their ultimate faith in a God they believe constructed and presides over a natural system that runs according to a ruthless cycle of death and destruction.

They seem to have a point.

I think human beings tend not to want to face evil. It’s intimidating, it’s disheartening, and it can lead to despair.

Darwin makes us face evil. That’s a good thing because it forces us to be realistic. We read Psalm 23 about walking in the valley of the shadow of death and fearing no evil, and we think OK, God is the good shepherd, and we’re all fine. And then our child gets cancer, and this completely destroys our faith.

But what God do you believe in? Do you think God is not going to let your child get cancer or get shot or get run over or get AIDS? It is naive to think God creates a bubble around us. It’s completely irresponsible to be in denial about evil.

We have to thank Darwin for forcing us to look at the fact of evil, because doing that means we also have to look more carefully and more gratefully at the gift of grace.

Faith in divine power is an abiding trust in the steadfastness of the power of God’s love in the midst of human suffering. The name given to the child Jesus, Emmanuel, “God with us,” suits the great blessings of our lives as well as our disappointments, trials, and struggles.

We modern people tend to think of death as the greatest evil. But for Christians death is a relative evil. The worst evils are the moral ones in which we knowingly and freely harm other people without justifcation, in which we inflict violence on people who don’t deserve it—the suffering of the innocent that we participate in.

A lot of human harm and destruction that we attribute to nature is caused by human social injustice. When a flood wipes out a village, we think it’s too bad people have to live in a flood plain in Bangladesh, but why are people forced to live there?

Why do people live below sea level in the Ninth Ward in New Orleans? Hurricane Katrina was not strictly a natural disaster but one aggravated massively by injustice and corruption, by racism and economic exploitation. Why is it that people are dying of AIDS in such huge numbers in Africa but no longer in San Francisco or New York or Los Angeles? That’s another issue of social injustice.

Ultimately there is no explanation to the problem of evil. The big challenge is how we respond to it.

What about our personal suffering?

Darwin helps us think in the broadest possible biological framework when we ask why bad things happen to good people. It’s not that there’s a ball of karma and whatever you do to others is going to come back later and be done to you. And it’s not that God is doling out retribution for sinners. Jesus rejected that view, but a lot of Catholics still have it.

I have a student whose 20-year-old roommate has a disease that causes all her hair to fall out. There’s no cure for it, and the girl is racked by the question of what she did to deserve it. She’s constantly searching her past for some great sin. Somehow she absorbed the idea that God is just, and if you’re punished you’re being punished justly. This is an anti-Christian idea.

The people who pay the worst for this approach to the moral order of the universe are poor people. When successful people look at them, they say the poor must deserve what they’ve got. They’re lazy or they’re stupid, so they deserve it.

Darwin helps us not to over-individualize suffering or moralize disease. I think that’s a very healthy thing. He helps us face suffering as a fact of the natural world.

Does evolution affect the way we see ourselves as human beings?

Evolution makes our understanding of who we are more complex. Certainly part of living in the 21st century is that we feel less certain about who we are and where we’re going. That’s why fundamentalism has such appeal. It says we can be certain: Here’s what we need to affirm in faith and how we need to live.

The alternative to evolution would be to take the old view of the human being basically as a soul in a body. We make choices in life: If we make the right choices, we’re given eternal reward, and if we make the wrong choices we go to hell. That was very clear. And for many people the list of things you could do and go to hell was extensive.

Now we think of human beings as a lot more complicated, of culpability as being harder to detect sometimes. We recognize our actions as contingent and conditioned by a lot of factors over which we have no control. Our judgment has to be somewhat restricted, and we have an invitation to respond to people with mercy.

Is human nature bad or good according to Darwin?

The Darwinian view is that human beings are basically selfish but can learn to be loving to family members and friends under the right circumstances. Darwin thought that one of the advantages of the church at its best was to help us become more altruistic people.

But he was also acutely aware of the limitations built into human nature regarding our altruism for strangers or outsiders or enemies and thought it was a mistake to expect people to be more altruistic than they could be. We might be Good Samaritans to our brother or cousin or neighbor on the road but not to a complete stranger. Darwin would understand why the priest and the Levite walk by the man on the other side of the road in that parable.

Darwin may assist us in describing an aspect of human nature, but it shouldn’t be taken as providing a sufficient ethic for Christians. Darwinians say it’s possible for people to live in very different kinds of moral communities. Some are just societies of individuals locked in perpetual conflict, as we see in failed states like Somalia.

So the challenge is really about the kinds of communities we want to develop. How strongly do we want to invest in structures and policies that promote human friendship, human growth for everybody in the community and not just for some members?

You write of solidarity as the central Christian response to Darwin. Why?

Darwin is associated with individualism, competition, and exploitation of the weak—the survival of the fittest. It often gets expressed by an ethic of the powerful and has been picked up by our own culture, which is highly individualistic. That has generated some good things, but it also can be very heartless and cruel, especially to people who are vulnerable and marginalized.

I think the challenge for Christian ethics after Darwin is really the challenge of solidarity. How do we develop the capacity to care for others? How do we form communities that are inclusive? How do we reach out to the marginalized when we’re constantly told to look out for ourselves? How do we identify with people who are not like us, who do not have the same skin color or the same economic situation, the same education, the same language?

Darwin argues that we have a tendency to group people into “us” and “them.” We’re good to the “us” group, and we either exploit or protect ourselves from “them.” When I was a kid it was we Americans againts the Communists, who had replaced the Nazis. Now we have the terrorists.

A lot of Christian ethics in the New Testament is about breaking down the barriers that make it possible to be indifferent to or exploit others. The parable of the Good Samaritan is the classic case of that. The Samaritan was the enemy, but in the story he is the one who exemplified compassion for the other.

How do we create that solidarity? That’s the challenge to the church—to develop communities that are not just institutions but places where people feel they belong, where they learn and grow in faith, where they identify with the community and its way of life.

It has to be a community of justice formed by love. How’s that for a project?

This article appeared in the February 2009 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 74, No. 2, pages 18-22).

Image: Wikimedia Commons