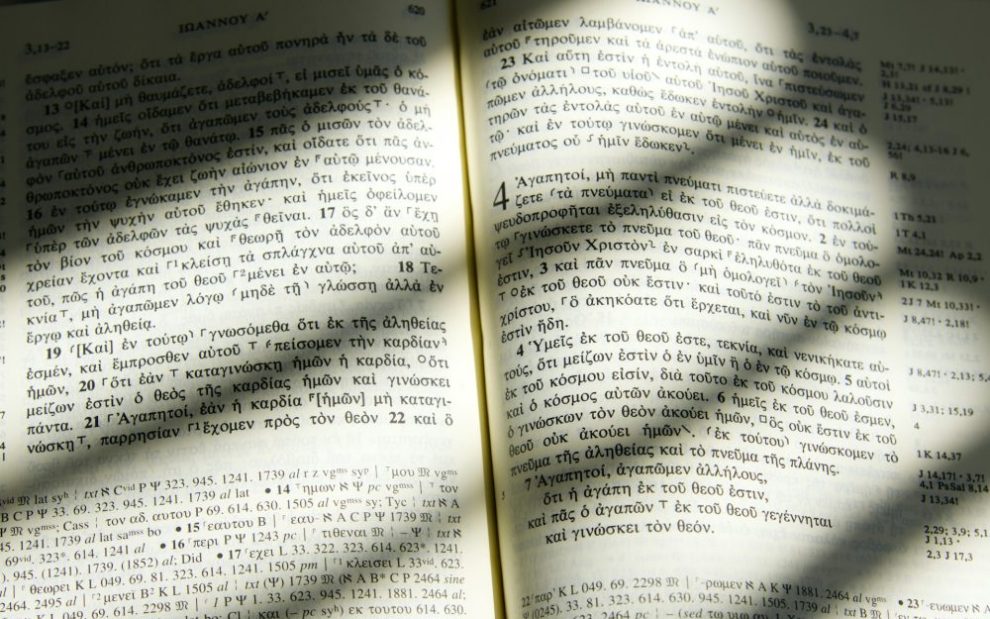

Unless you happened to grow up speaking Ancient Greek and Hebrew (with a smattering of Aramaic for good measure), the words you are familiar with from scripture, whether read aloud at Mass or silently at home, are not the same words divinely inspired millennia ago. They are the product of the work of countless translators laboring to render ancient tongues into living, understandable vernacular.

The translation that has shaped your prayer life and spiritual imagination is itself part of a rich, ongoing tradition—one link in a long chain of linguistic evolution that stretches from early Christian communities to the present day. Each generation truly receives the Word anew, translated with care to speak to its own time and place.

In the very near future, a new link will be added to that ever-growing chain: This month, the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops approved a new Bible translation in an overwhelming 216-4 vote, to be called “The Catholic American Bible,” expected for release in 2027.

Speaking to The Catholic Standard, Bishop Steven J. Lopes, chairman of the USCCB’s Committee on Divine Worship, described the new translation as seeking to create a “common text between the lectionary at Mass, the Scripture that is used in the Liturgy of the Hours and a Bible text that you can have as a physical Bible for your own private prayer and devotion”.

The Catholic American Bible (CAB) will replace the New American Bible, Revised Edition (NABRE), which was released in March 2011 after 20 years of consultation and revision. The CAB is not a completely new translation: its Old Testament will be a revised version based on the NABRE, replacing the Book of Psalms with The Abbey Psalms and Canticles—a translation created by monks at Conception Abbey in Missouri. The New Testament, however, has been newly translated, with work beginning in 2013 soon after the release of the NABRE, with 5 editors and 18 revisers contributing to the project.

According to coverage from The Pillar, the translators balanced dual goals: improved readability and suitability for liturgical proclamation while maintaining scholarly rigor. This reflects an ongoing tension in biblical translation—how literal should a translation be? How much should translators prioritize the beauty and flow of English over strict adherence to ancient sentence structures? The Catholic American Bible aims to split this difference, offering a text that works equally well for private meditation, public worship, and scholarly settings.

The process by which Catholics receive approved translations has evolved significantly. Before 1983, translations required approval either from the Apostolic See or from a local diocesan bishop, a system that granted individual bishops considerable authority. The 1983 revision to the Code of Canon Law changed this, entrusting approval to both the Apostolic See and bishops’ conferences such as the USCCB. This shift centralized the approval process and guaranteed Vatican oversight.

The journey toward the Catholic American Bible began decades ago. The original New American Bible (NAB) was published in 1970, stemming from the Confraternity Bible project, which responded to Pope Pius XII’s 1943 encyclical Divino Afflante Spiritu (On Promoting Biblical Studies) calling for translation from the original languages of scripture rather than from the Latin Vulgate. Fifty-one biblical scholars worked on the New American Bible from 1944 to 1970, representing a massive collaborative effort.

The NAB became the standard for American Catholic worship, but other English-speaking countries approved different translations—the Jerusalem Bible in England and Wales, the Revised Standard Version, Catholic Edition in Canada for certain uses, and others.

As a global church whose history spans thousands of years, the project of translation will likely always be essential to life in the Catholic church, whether for scripture, or the liturgy, or encyclicals, or even just Christmas cards. As such, we shouldn’t expect the Catholic American Bible to put the final pin in this saga—the current translation of the Mass is just about as old as the NABRE, so perhaps we should be preparing also for a new translation on the liturgical front.

As American Catholics anticipate this new translation—and wait, perhaps, for a translation of the Mass to match—it’s worth pausing to reflect on our own relationship with scripture and the liturgy. What do we actually need from a Bible translation? What’s missing from current liturgical translations? What would help us encounter the gospel more deeply? These are the questions we’d like you to ponder in the latest U.S. Catholic Sounding Board survey.

Image: Unsplash/Skyler Gerald

Add comment