Few have written authoritative biographies of the 20th-century spiritual giants Dorothy Day, co-founder of the Catholic Worker, and Thomas Merton, the celebrated Trappist monk and writer. Fewer still knew them both. But Jim Forest, a former Catholic Worker himself, did, and his unique insight reveals the human side of two figures many Catholics revere as saints, if as yet uncanonized.

Why the interest in these two people, both dead for decades? “Merton is just a perennial, like certain plants that refuse to stop blooming no matter how many years pass,” says Forest of the monk, who died in 1968, but whose writings are still not all published. “There’s a new book by him coming out every year or two.”

As for Day, with whom Forest lived as a member of her staff, “Her canonization proceedings have gradually made people more and more curious: Who is this Dorothy Day?”

The close friendship between Day and Merton, rooted in their common commitment to nonviolence and the works of mercy, is a fact known to few of their admirers. At heart, they shared a desire to restore to the church its early refusal of violence for any reason.

“If you were to be baptized in the early centuries, you had to make a commitment not to kill anybody, period,” says Forest. “How did we lose that? Merton and Dorothy were two of the people in the 20th century who helped to unpack those boxes that had been pushed up into the attic.”

Dorothy Day lived in New York City among the poor, and Thomas Merton was a monk in rural Kentucky. How did you come to know them both?

When I first came to the Catholic Worker in 1960, I was still in the Navy. I was 19 years old, working at the U.S. Weather Bureau as a young meteorologist and taking kids to Mass on Sunday from a little institution in Washington where I was volunteering in my spare time. I found copies of Dorothy’s newspaper, The Catholic Worker, in the library at this particular parish, Blessed Sacrament, and became curious about the woman. One weekend I went up from Washington to New York to see what the Catholic Worker was all about.

In New York I was given a bag of mail to take to her in Staten Island. She was sitting there with a letter opener at the end of a table with a half dozen people sitting around. One of the rituals of life, as I discovered, was Dorothy reading the mail aloud to whoever happened to be there and telling stories.

One of the letters was from Thomas Merton, and I was absolutely astounded that Dorothy Day, who was very much “in the world,” was corresponding with Thomas Merton, who had left the world with a resounding slam of the door. Of course, they were both members of the Catholic Church and both writers, but Merton had taken the express train out of New York City for good, and Dorothy lived at its very heart.

Dorothy periodically got arrested; Merton certainly did not. Dorothy was very much under a cloud from the point of view of many Catholics because of her anti-war activities, and Merton was regarded as one of the principal Catholic writers in the world. But if they had been brother and sister they couldn’t have been very much closer.

How would you introduce these two figures to someone who doesn’t know them?

I might start with a photo: Dorothy Day between two policemen, awaiting arrest at age 75. It was her last arrest, and you can see that this is a person worth knowing about, somebody who never stopped being disturbed about things that were disturbing, and she did it without hating anybody. She had a gift for seeing injustice and responding without rage but with persistence.

She’s looking at these two policemen like a concerned grandmother of two kids who have their water pistols ready to open fire on grandma—but she’s definitely not in a state of enmity with these two boys and their big guns.

In the case of Merton it’s more difficult because monastic life is so removed. The average age of a monk at Merton’s Abbey of Gethsemani now is 70. Today there aren’t a lot of young people thinking of becoming monks, whereas 50 years ago a lot of people were. I remember when I first saw Merton—there were no author photographs on his books, so you had no idea what he looked like—I sort of imagined some skinny person fasting all hours of the day, certainly not a person with a sense of humor.

When I actually saw him for the first time in the monastery, he was on the floor with his feet in the air and clutching his tummy, laughing so hard that he was a shade of red.

What was he laughing about?

Merton had invited me to come down to the monastery, and I hitchhiked down because of my economic situation. It was in the middle of winter, 1962, and by the time Bob Wolf, one of my friends at the Catholic Worker, and I arrived, it had been two and a half days of the worst weather I’d ever experienced.

When we finally got to the abbey, we hadn’t had a shower in two and a half days, so we probably had a pretty rich aroma. I had gone into the chapel loft at the monastery to pray, as I was excessively pious in those days. Bob more sensibly had collapsed on his bed in the guest house.

Soon I could hear in the distance this funny sound that seemed like laughter but, of course, it couldn’t be laughter because this was a monastery. I followed the noise into Bob’s room, where I found both Merton and Bob laughing. It was, of course, the “Catholic Worker perfume” that had been inhaled by Merton that set him off.

Why was meeting Merton such a big deal to you?

I can only compare it to meeting someone like Oprah Winfrey today. You could not walk into a bookshop in America then without finding Merton’s autobiography, The Seven Storey Mountain. For tens of thousands of people, it was a life-changing book. It’s a perennial bestseller, probably the most important religious autobiography that had been written in 200 or 300 years. It was the beginning of a succession of books by Merton, all of which were automatic bestsellers.

Most of the people who read it didn’t become monks. But they did discover a kind of monastic place inside themselves where they could live a more coherent spiritual life. They found a core, a center, an anchor of some kind, and it opened their eyes in ways they hadn’t been opened before.

Was Dorothy Day as well known?

No, but on the other hand you could not walk into a Catholic church in America and not run into somebody who knew about the Catholic Worker. There were Catholic Worker houses of hospitality all over the country. The Catholic Worker newspaper was one of the most widely read Catholic publications in the United States with 100,000 copies printed every month. And once you became interested in Day, you were likely to read her autobiography, The Long Loneliness.

How did Merton and Day become friends?

It was a friendship of letters; they never actually met. Their oldest surviving letter is from December 1956, from Dorothy to Merton. She had received the news that he had offered Christmas Mass for her and the Catholic Worker and wanted him to know that “this has made me very happy indeed.” She goes on to say, “We have had a very beautiful Christmas here and quite a sober and serious one, too. There have been occasions in the past when the entire kitchen force got drunk, which made life complicated, but you must have been holding them up this year. Please continue to do so.” You get a sense of the frankness of their exchanges.

The next letter that escaped the vicissitudes of time is also from Dorothy, from June 1959. It’s a reply to a letter from Merton, and she apologizes for not having answered more quickly and also recalls with gratitude the copies of The Seven Storey Mountain he had sent to her way back in 1948.

That might have been the beginning, just Merton sending her a box of books. So Merton’s interest in Dorothy goes back at least to 1948.

Why do you think Merton was interested in Day and the Worker?

The big decision for Merton was whether to be part of Catherine Doherty’s Friendship House in Harlem near Columbia, where he was studying, which was like the Catholic Worker, or to go to Gethsemani and become a monk.

Monastic life tilted heavily toward prayer, and ultimately Merton realized there was just something mysterious in him that pulled him toward that vocation. He didn’t feel it was necessarily as high a vocation as the works of mercy, but it was the one that God was calling him to. But that tension was always there, and he had a sense of gratitude that the Catholic Worker existed. Having a relationship with Dorothy allowed him to be a part of the work he hadn’t been led to do. As he wrote to Dorothy in December 1963, “If there were no Catholic Worker and such forms of witness, I would never have joined the Catholic Church.”

How did they influence each other?

I think Merton probably had less influence on Dorothy than she had on him, actually. Merton was trying very hard to write through the church censors—the abbot-general of his order blocked some of his writings about war and peace, for example. But Merton mainly wanted to reach Catholics who were bewildered by the idea of nonviolent, disarmed life, with works of mercy as a core of Christian life. I think he tried harder than Dorothy to communicate with people who didn’t completely share a pacifist view, and she was impatient with him for doing so.

Dorothy was very outspoken: no footnotes, no commentaries, just bang, there it is. Merton would make a great effort to meet people midway, which I think was one of his talents.

Merton’s voice changed all the time depending who he was talking to. If he was talking to a Quaker, he might use Quaker vocabulary. The same if he was talking to a Muslim. He created spaces in which dialogue occurred that might not happen otherwise. Merton had this facility to study and appreciate radically different points of view and somehow integrate them into his style with some people.

Dorothy didn’t have a vocabulary for talking to Buddhists—she was so Catholic. I can remember having to argue Dorothy into publishing articles by Thomas Merton in The Catholic Worker because he wasn’t taking the pacifist position that Dorothy took. Can you imagine having to convince the editor of The Catholic Worker to publish an article by Thomas Merton?

Did he influence her in terms of prayer?

Dorothy was there already. She wouldn’t have lasted five years at the Catholic Worker if she didn’t pray.

Of all the people I’ve known in my life, including Thomas Merton, I haven’t known anybody with a more disciplined spiritual life than Dorothy Day: Mass every day, rosary every day, confession every week. A community of Benedictine monks sent us prayer booklets for use during the day at the Worker—lauds, vespers, compline. We used them until they were worn out and then they’d send us more.

How was Day’s approach to war and peace different from Merton’s?

I can remember going with Dorothy one night when she was speaking at New York University on Washington Square. I was impressed by how much hostility there was from some of the students because of her antiwar stance. The Cold War was very cold, and anybody who was seen as a little short on the patriotic side—which meant an uncritical, enthusiastic support of the military activities of the United States government—came under suspicion.

One of the students said, “Well, Ms. Day, you talk about loving enemies, but just what would you do if the Russians were to invade?” Dorothy said, “I would love them the same as I love anybody else that comes here. Jesus has said to love your enemies; that’s what I try to do. I would open my arms and do my best to make them feel welcome.”

It was an absolutely scandalous answer, but it was straight out of the New Testament. It was like a lightning bolt, this shocking simplicity of the gospel. Dorothy knew enough by that time to be able to speak that way without apology or embarrassment.

I suppose the young man who asked that question has never forgotten the answer. He probably will come back to it again and again and move from scandal and shock to maybe even thinking she was onto something.

It wasn’t just words. Dorothy was in situations time and time again when she was confronted with people who were dangerous, and she did exactly what she hoped to do. She responded to them in a caring, motherly way.

How do you think Merton and Day would respond to today’s wars?

Dorothy would be doing the kind of things Kathy Kelly of Voices for Creative Nonviolence and other peace activists are doing: going to Iraq, going to Afghanistan, meeting with people, helping them, making known through writing and photography what the world is doing to human beings in these situations.

I saw a picture on a poster in Milwaukee a couple of days ago that peace activists use at a weekly vigil on the Marquette campus. It is an American soldier—helmet, battle fatigues, gun at his side—holding the dead body of a child, the soldier obviously weeping. That’s the kind of imagery we’re not seeing on the front page of any newspapers in America, but that’s the reality of war, and Dorothy would be encouraging young people to bring it out.

One of the things Merton stressed that we’re missing in our discussions of war is what he called the human dimension. We have to try to bring the face of suffering people to the fore and see what we can do to make that suffering happen less often, with less dreadful consequences.

You’ve talked about Thomas Merton’s sense of humor. What about Dorothy Day? Was she ever funny?

One of my favorite stories of Dorothy was the moment when a quite well-dressed woman came in to the Worker. She took a diamond ring from her finger and handed it to Dorothy. Why she was moved to do that, I have no idea. Dorothy thanked her politely with no more fuss than she would if the woman had brought a dozen eggs.

A little while later a woman that we didn’t particularly enjoy seeing showed up. I think her name was Catherine, but we called her “the weasel.” She was, as far as we could tell, genetically incapable of saying thank you. Dorothy reached into her pocket and said, “I have something for you”—and gave her the diamond ring.

I don’t know if it was me or somebody else who went to Dorothy afterward and said, “You know, Dorothy, I could have taken that ring up to West 47th Street to the Diamond Exchange, and we could have paid her rent for years to come.” She responded, “Well, if she wants to sell the ring and go to the Bahamas, she can do so. But she might also like to just wear the ring. Do you think God made diamonds just for the rich?”

Despite their differences, how are Day and Merton most similar?

You would think that they wouldn’t have much in common, but the more you look the more you see how much they complement each other.

I think they both represent a radical search for a deeply rooted spiritual life that is not separate from the world. We always hear the commandment, “Love God, and love your neighbor,” but one or the other usually takes priority. Thomas Merton and Dorothy Day were both remarkably successful in finding that balance point in terms of their own unique identities.

The balance is slightly different, but the scales are very similar, which makes them convincing to us today, each in their own way.

This article appeared in the November 2010 issue of U.S. Catholic.(Vol. 76, No. 11, pages 18-21).

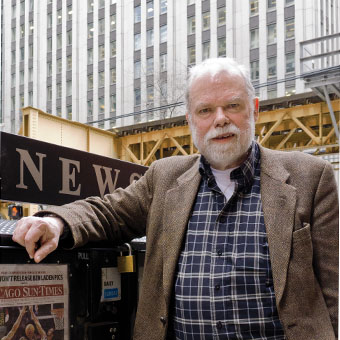

Image: Photo of Jim Forest by Tom Wright

Add comment