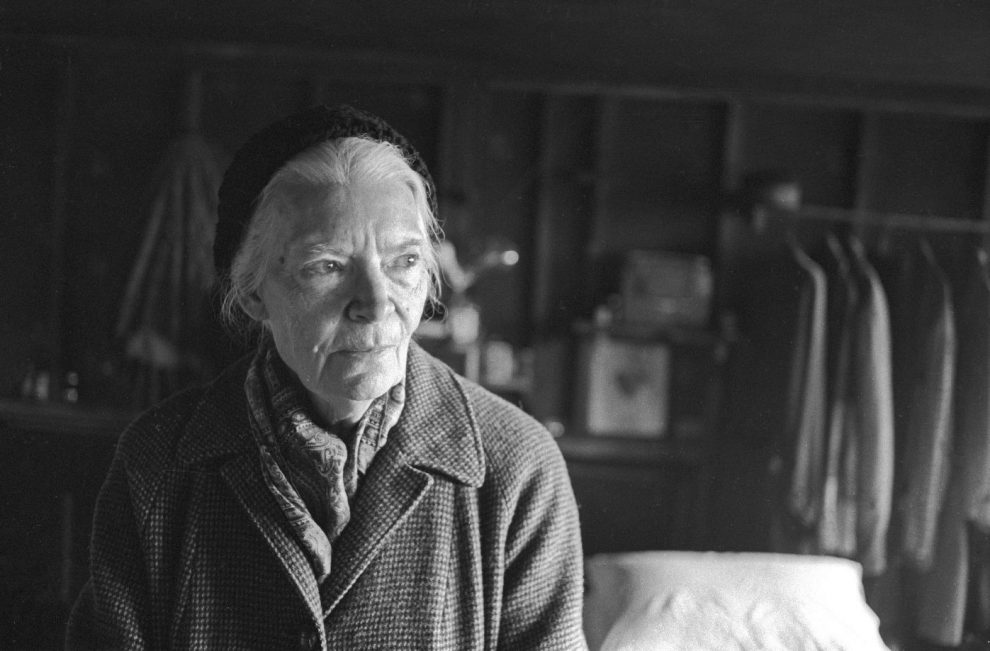

First of all, Dorothy Day taught me that justice begins on our knees. I have never known anyone, not even in monasteries, who was more of a praying person than Dorothy Day. When I think of her, I think of her first of all on her knees praying before the Blessed Sacrament. I think of those long lists of names she kept of people, living and dead, to pray for. I think of her at Mass, I think of her praying the rosary, I think of her going off for Confession each Saturday evening.

If you find the life of Dorothy Day inspiring, if you want to understand what gave her direction and courage and strength to persevere, her deep attentiveness to others, consider her spiritual and sacramental life.

“We feed the hungry, yes,” she said. “We try to shelter the homeless and give them clothes, but there is strong faith at work; we pray. If an outsider who comes to visit us doesn’t pay attention to our prayings and what that means, then he’ll miss the whole point.”

Second, Dorothy Day taught me that justice is not just a project for the government, do-good agencies, or radical movements designing a new social order in which all the world’s problems will be solved. It’s for you and me, here and now, right where we are.

Jesus did not say “Blessed are you who give contributions to charity” or “Blessed are you who are planning a just society.” He said, “Welcome into the Kingdom prepared for you since the foundation of the world, for I was hungry and you fed me.”

At the heart of what Dorothy did were the works of mercy. For her, these were not simply obligations the Lord imposed on his followers. As she said on one occasion to Robert Coles, “We are here to celebrate him through these works of mercy.”

Third: The most radical thing we can do is to try to find the face of Christ in others, and not only those we find it easy to be with but those who make us nervous, frighten us, alarm us, or even terrify us. “Those who cannot see the face of Christ in the poor,” Dorothy used to say, “are atheists indeed.”

Dorothy was an orthodox Catholic. This means she believed that Christ has left himself with us both in the Eucharist and in those in need. “What you did to the least person, you did to me.”

Her searching of faces for Christ’s presence extended to those who were her “enemies.” They were, she always tried to remember, victims of the very structures they were in charge of.

She sometimes recalled the advice she had been given by a fellow prisoner named Mary Ann, a prostitute, when she was in jail in Chicago in the early 1920s: “You must hold up your head high and give them no clue that you’re afraid of them or ready to beg them for anything, any favors whatsoever. But you must see them for what they are—never forget that they’re in jail too.”

Fourth, I learned that beauty is not just for the affluent. Tom Cornell tells the story of a donor coming into the Catholic Worker and giving Dorothy a diamond ring. Dorothy thanked her for it and put it in her pocket. Later a rather demented lady came in, one of the more irritating regulars at the house. Dorothy took the diamond ring out of her pocket and gave it to the woman.

Someone on the staff said to Dorothy, “Wouldn’t it have been better if we took the ring to the diamond exchange, sold it, and paid that woman’s rent for a year?”

Dorothy replied that the woman had her dignity and could do what she liked with the ring. She could sell it for rent money or take a trip to the Bahamas. Or she could enjoy wearing a diamond ring on her hand like the woman who gave it away. “Do you suppose,” Dorothy asked, “that God created diamonds only for the rich?”

Fifth, Dorothy taught me that meekness does not mean being weak-kneed. There is a place for outrage as well as a place for very plain speech in religious life.

She once told someone who was counseling her to speak in a more polite, temperate way, “I hold more temper in one minute than you will hold in your entire life.”

Or her lightning-like comment, “Our problems stem from our acceptance of this filthy, rotten system.”

Sixth, I learned from Dorothy to take the “little way.” The phrase was one Dorothy borrowed from Saint Therese of Lisieux, the Little Flower. Change starts not in the future but in the present, not in Washington or on Wall Street but where I stand.

Change begins not in the isolated dramatic gesture or the petition signed but in the ordinary actions of life, how I live minute to minute, what I do with my life, what I notice, what I respond to, the care and attention with which I listen, the way in which I respond.

As Dorothy once put it: “Paperwork, cleaning the house, dealing with the innumerable visitors who come all through the day, answering the phone, keeping patience and acting intelligently, which is to find some meaning in all that happens—these things, too, are the works of peace, and often seem like a very little way.”

Or again: “What I want to bring out is how a pebble cast into a pond causes ripples that spread in all directions. Each one of our thoughts, words, and deeds is like that.”

What she tried to practice was “Christ’s technique,” as she put it, which was not to seek out meetings with emperors and important officials but with “obscure people, a few fishermen and farm people, a few ailing and hard-pressed men and women.”

Seventh, Dorothy taught me to love the church and at the same time to speak out honestly about its faults. She used to say that the net Saint Peter lowered when Christ made him a fisher of men caught “quite a few blowfish and not a few sharks.”

Dorothy said many times that “the church is the cross on which Christ is crucified.” When she saw the church taking the side of the rich and powerful, forgetting the weak, or saw bishops living in luxury while the poor are thrown the crumbs of “charity,” she said she knew that Christ was being insulted and once again being sent to his death.

“The church doesn’t only belong to the officials and bureaucrats,” she said. “It belongs to all people, and especially its most humble men and women and children.”

At the same time I learned from her not to focus on the human failings so obvious in every church, but rather to pay attention to what the church sets its sights on. We’re not here to pass judgment on our fellow believers, whatever their role in the church, but to live the gospel as wholeheartedly as we can and make the best use we can of the sacraments and every other resource the church offers to us.

“I didn’t become a Catholic in order to purify the church,” Dorothy told Coles. “I knew someone, years ago, who kept telling me that if [the Catholic Workers] could purify the church, then she would convert. I thought she was teasing me when she first said that, but after a while I realized she meant what she kept saying.

“Finally, I told her I wasn’t trying to reform the church or take sides on all the issues the church was involved in; I was trying to be a loyal servant of the church Jesus had founded. She thought I was being facetious. She reminded me that I had been critical of capitalism and America, so why not Catholicism and Rome?

“My answer was that I had no reason to criticize Catholicism as a religion or Rome as the place where the Vatican is located…. As for Catholics all over the world, including members of the church, they are no better than lots of their worst critics, and maybe some of us Catholics are worse than our worst critics.”

Last but not least: I learned from Dorothy Day that I am here to follow Christ. Not the pope. Not the ecumenical patriarch. Not the president of the United States. Not even Dorothy Day or any other saint.

Christ has told us plainly about the Last Judgment, and it has nothing to do with belonging to the right church or being theologically correct. All the church can do is try to get us on the right track and keep us there. We will be judged not on membership cards but according to our readiness to let the mercy of God pass through us to others. “Love is the measure,” Dorothy said again and again, quoting Saint John of the Cross.

Hers was a day-to-day way of the cross, and just as truly the way of the open door. “It is the living from day to day,” she said, “taking no thought for the morrow, seeing Christ in all who come to us, and trying literally to follow the gospel that resulted in this work.”

Jim Forest began his association with Dorothy Day in 1961, when he moved to New York City to join the Catholic Worker community there. A recent convert to Catholicism, he had been discharged from the U.S. Navy as a conscientious objector.

Nearly 30 years earlier Day, together with Peter Maurin, began a Depression-era newspaper called The Catholic Worker. And from this early collaboration an entire movement was born—the Catholic Worker movement, which has become well known for its houses of hospitality for people in need and for its strong stance against injustice and violence.

Forest went on to become managing editor of The Catholic Worker newspaper, and it was his work on the paper that first put him in touch with Catholic monk Thomas Merton.

This article originally appeared in the July/August 1995 issue of Salt of the Earth magazine.

Image: Bob Fitch photography archive, © Stanford University Libraries

Add comment