UPDATE: Since this article was published, the diocese of Phoenix has overturned its initial decision about eliminating communion from the cup. Read this USCatholic.org blog post for more information.

New rules in two dioceses make communion from the cup an endangered species.

While Catholics across the United States are getting their tongues around the new translations of the Mass, Catholics in two U.S. dioceses will also be taste-testing another change: regular communion from the cup will be disappearing.

Phoenix Bishop Thomas Olmsted’s new directives for communion from the cup, according to the diocesan website, will allow the assembly to receive the blood of Christ “at the Chrism Mass and feast of Corpus Christi. Additionally it may be offered to a Catholic couple at their wedding Mass, to first communicants and their family members, confirmation candidates and their sponsors, as well as deacons, non-concelebrating priests, servers, and seminarians at any Mass,” along with religious in their houses and retreatants. Bishop Robert Morlino of Madison, Wisconsin made a similar decision.

The effect of the change, intended or not, is that the blood of Christ will separate some members of the assembly from others, notably priests and deacons (whether they are functioning in their liturgical roles or not), and seminarians and servers.

A close reading of the Phoenix rationale for the decision quickly makes clear a primary purpose: to eliminate extraordinary (lay) ministers of the Eucharist, because too many of them result in “obscuring the role of the priest and the deacon as the ordinary ministers.”

This fear of “disproportionately multiplying” communion ministers is then applied to the feast of Corpus Christi, one of the few times communion under both species will be permitted. In that instance if a parish is lacking enough “ordinary ministers,” “it is common sense that [the pastor] would not be able to judge the necessary conditions as met,” because he would need a “disproportionate” number of lay ministers to distribute the blood of Christ. In other words, no cup—even on the Solemnity of the Body and Blood of Christ—all for the sake of reinforcing the distinct (and obvious) roles of the ordained.

The diocesan reasoning invokes the 2005 expiration of a Vatican permission granted in 1975 that allowed wide use of the cup but disregards the more general liturgical law that allows the diocesan bishop to make the cup widely available. The diocese even bizarrely argues that communion under the form of bread alone is a greater sign of Catholic unity because most Catholics in the world don’t get to receive from the cup. Because the faithful of the rest of the world are robbed of the fullness of the eucharistic symbol, the reasoning goes, Catholics of the Diocese of Phoenix should be, too.

Setting aside legal arguments for when and if baptized people should be allowed to obey Christ’s command to “take and drink”—along with the fact that communion in both kinds is the church’s most ancient practice—basic sacramental theology shows just how ridiculous this decision is. Sacraments by definition “effect what they signify,” that is, through their symbols—both objects (bread and wine) and actions (breaking, sharing, eating, and drinking)—Christ is truly present.

It’s true that the bread alone is sufficient for the full theological reality of Christ’s eucharistic presence, but why we should settle for sufficient when we can have the entire eucharistic symbol, which better communicates the fullness of the mystery we celebrate? Should we restrict the amount of water used in baptism or the amount of oil when we anoint the sick? Neither should we settle for a merely vicarious drinking from the cup.

It is clear that in matters liturgical, the Roman Catholic Church is deep in a period of retrenchment marked by a re-clericalization of the Eucharist, if not an outright repudiation of the pastoral reform of the Mass authorized by the Second Vatican Council. As the situation in Phoenix and Madison makes painfully obvious, those whose membership in the church is “limited” to baptism—the laity—have little recourse as they are stripped of the active participation that was to be the hallmark of the renewed liturgy.

The restoration of the regular reception of the blood of Christ by the faithful, though never fully implemented, was a giant step forward in returning to the baptized their full participation in the sacred mysteries of our faith. Let us hope these ill-conceived decisions by the bishops of Phoenix and Madison don’t spread beyond the borders of their dioceses.

This article appeared in the December 2011 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 76, No. 12, page 8).

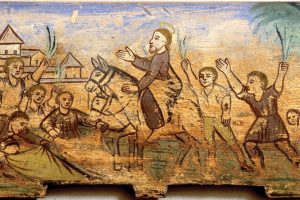

Image: Tom Wright

Add comment