Kelly Latimore first started painting icons while living with the Common Friars, an Ohio-based intentional community whose concern for the earth has been instrumental in shaping the group’s vision. One of its members often posed a question drawn from Matthew’s gospel and quoted in their Rule of Life: “How do we become people who, in Jesus’ words, ‘consider the lilies of the field?’ ” This allegory about arranging our priorities concludes by counseling believers to “seek first (God’s) kingdom and righteousness” or, in other translations, God’s “way of holiness” (6:28–34).

This biblical passage aptly outlines how icons function. More than a visual pleasure—and that value should not be discounted—these images of holy ones remind the faithful of our call to sanctity.

Traditionally iconographers trace the lines of extant forms; the goal, contrary to the autonomous nature of contemporary painting, is producing a replica that eschews innovation to hand on an unadulterated spiritual precept. For this reason, some speak of “writing” rather than “painting” an icon to emphasize the theological message associated with a specific representation.

Whatever language one chooses to use, these images stand before us as a challenge and mirror: How does my life measure up to the “way of holiness” recorded on their pigmented surfaces?

Mining the wisdom of ecological consciousness and scriptural texts, Latimore produced his first icon, Christ: Consider the Lilies. His struggle to root himself in gospel living within a community manifests itself physically as he labored to manipulate the paint he was applying. Lines are tentative rather than sure; his composition and proportions resist an assured resolution. Jesus seems to be slipping off his nimbus as he looks down rather surprised to be holding a bouquet. Meanwhile, the Holy Spirit, shown conventionally as a bird in flight, seems poised to exit the picture plane.

Painted on inexpensive masonite, this icon’s endearing qualities consist of equal parts first attempt and the maker’s candor. Instead of relying upon expected patterns, Latimore’s work seems to bear witness to the journey upon which he embarks to generate an image. His technique will undoubtedly become more refined as he continues to paint; I, for one, hope that his production never becomes so facile that his icons cease to tangibly communicate the effort expended to create them. Those for whom these likenesses function as avenues to prayer are wisely reminded of the effort, discipline, and persistence required to be faithful disciples of Jesus.

The earliest Christian iconographers portrayed the saints revered by local faith communities; some of these were recognized throughout Christendom and others were subject to only regional devotion. Latimore, like other contemporary Western practitioners, has retrieved this latter practice in choosing his subjects such as Mother “Harris” Jones.

Early in her life, Mary Harris immigrated to Canada because of the Irish potato famine. Widowed at the age of 30 when her husband George Jones and all four of their children died in a yellow fever epidemic in Memphis, she moved to Chicago and set herself up as a dressmaker. Four years later, her shop was destroyed in the Great Chicago Fire of 1871. She emerged from these losses sensitive to the downtrodden and devoted the rest of her life to organizing labor unions and fighting for workers. Her famous quote “pray for the dead and fight like hell for the living” reveals both her heart and her fortitude.

Latimore shows her haloed and holding the Christ child. Standing in front of a factory spewing fumes and in a field of common dandelions, Mother Jones protects Jesus and, by extension, all who are powerless. Clothed in a tattered garment, the savior of the world is presented as vulnerable; instead of holding his hand in a typical gesture of blessing, he raises it to mimic the hesitant wave of a shy child.

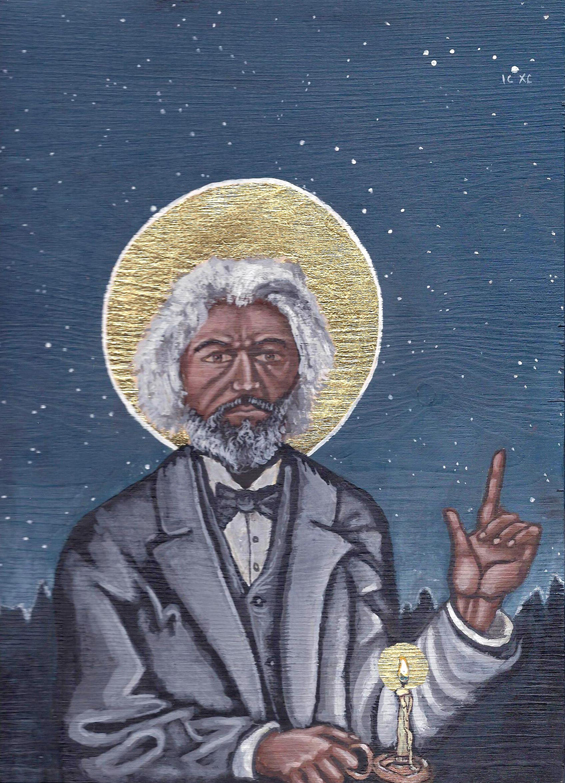

Believing there are “saints among us that haven’t been depicted,” Latimore turned to Frederick Douglass as an exemplar of holiness. Douglass, born into slavery and probably fathered by the man who owned him, refused to be confined by his origin. Learning to read in spite of laws that forbid the education of slaves, he spent his life, as his likeness shows, lighting candles rather than cursing the darkness. In his three-volume Autobiographies, Douglass noted that he “prayed for twenty years but received no answer until I prayed with my legs.”

His decision to escape exemplified the life of this respected, if controversial, 19th-century writer, speaker, and government official. As a person of action, his icon challenges a spirituality that holds prayer as a believer’s singular task. Our decisions and actions, even those some might label as dangerous, can be a faith-filled response to our relationship with God.

Latimore subtly reminds us of the untidy relationship between belief and action by having Douglass point to the North Star; famously used by those attempting to flee enslavement, the artist has labeled this celestial guide with the Greek abbreviation for Jesus Christ. The divine can be embedded in, rather that distant from, human history.

When asked to describe his vocation, Latimore replied that his favorite translation of iconographer is “depicter of forms taken from life.” This became his task when approached to create an icon for the Franciscan (Order of Friars Minor) novitiate. The result is Saint Francis and the Novices, an image more narrative painting than traditional icon.

In seeking to visualize the process of neophyte friars integrating the charism of St. Francis of Assisi into their lives, the artist turned again to the symbol of darkness vanquished by light. In the far right is the chapel of San Damiano, a place crucial to Francis’ self-understanding and the establishment of his order. Rather than locating Francis there, in the past, Latimore has painted him at a campfire.

The title implies that his companions are three novice friars, but their status in the order is less important than their dialogue with Francis. Gesturing as the teaching Buddha is often shown, Francis elicits different responses from each friar: one listens intently, another seems to verbalize his response, and the third ponders Francis’ wisdom as he gazes into the fire contemplatively. Though the setting is both romantic and charming, the surrounding dark woods becomes a reminder of the unknown future each friar and the order faces.

In a similar manner, Refugees: La Sagrada Familia uses night to signal peril. In probing a current parallel to the Holy Family’s flight into Egypt, Latimore sets out in search of what he describes as “the need for new images.”

In revisiting the angelic injunction to Joseph, “take the child and his mother, and flee” (Matt. 2:13), he directs our attention to the risky choices that families feel they must make today. Here we confront a protective and determined Joseph, a resolute though frightened Mary, and a powerless Jesus who must live with the decisions made for him; the cozy Christmas story ends with danger rather than safety.

In his striving to produce “the kind of images that will create dialogue,” Kelly Latimore might have begun with seemingly harmless wildflowers. His deliberations have yielded pointed questions and admonitions to see past various distractions to the today and tomorrow with enough troubles of their own (Matt. 6:34). As he wonders “what people and stories and images are here among us now,” he invites us to meditate upon the present attentively, to join him in considering the lilies. USC

For more information about Kelly Latimore and his icons, visit kellylatimoreicons.com.

This article also appears in the March 2018 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 83, No. 3, pages 28–33).

Add comment