No one was more excited to receive an acceptance letter to Arrupe College than the mother of Jontae Thomas. “She called me,” Thomas recalls. “Don’t you get the notification today?” she asked. Indeed, he did. Thomas called his mother back to share the good news. “She screamed for joy,” he says. But Thomas asked why his acceptance to Arrupe College was so important to her, when he’d also been accepted to other schools.

“I just like that school,” Thomas’ mother told him. Thomas understood why: Classes are small, and teachers know their students by name. They also serve as student advisers and “would always have their door open to us,” Thomas says. Most attractive of all was the opportunity to earn an associate degree without incurring financial debt.

Nineteen-year-old Thomas appears in a YouTube video about Arrupe filmed when he was still a student at Chicago’s Rauner College Prep. In the video, he explains the reasons why Arrupe is the right fit for him. At Rauner, part of the Noble Network of Charter Schools, higher education was prepared for and expected through the four years of high school. Thomas led tours of Rauner and learned about Arrupe when Derek Brinkley, Loyola University Chicago’s associate director of admission, paid a visit to his school. Thomas soon checked off the assets of this new initiative, which included its urban location. “It wasn’t far from home, and it felt like a nice place to be,” Thomas says.

Arrupe is more than that. The “junior” college, an extension of Loyola University Chicago, was created expressly to address the lack of accessible higher education for low-income families. Arrupe’s founder, Jesuit Father Michael J. Garanzini, hatched the idea as a timely, necessary way to improve the college’s graduation rates of students from challenged economic backgrounds. Garanzini’s concern was that the successful growth of Jesuit universities had created an elitist reputation.

Jesuit Father Stephen Katsouros, dean and executive director of Arrupe College, meets with a student on the first day of class.

The opportunity gap in higher education has received national attention. Political scientist Robert D. Putnam argues in his 2015 book Our Kids: The American Dream in Crisis (Simon & Schuster) that the notion that every person, if he or she works hard, should have the chance of getting ahead, is “no longer self-evident.”

No city knows that more than Chicago. In December 2014, the University of Chicago Consortium on School Research (CCSR) released a report estimating that only 14 percent of ninth graders in Chicago Public Schools will earn a four-year degree within 10 years of starting high school. That statistic is up from 8 percent in 2006, but the report highlights some alarming news: Students are unprepared for college, and they experience barriers to completing their education once they’re enrolled.

Garanzini designed Arrupe as part of a long-range plan to implement change, with the university absorbing the costs. He ran the proposal past administrators of various Chicago high schools—Catholic, public, and charter. It “was met with great excitement,” says Jesuit Father Stephen Katsouros.

Katsouros is the Jesuit that Garanzini recruited to run Arrupe (which is named after Father Pedro Arrupe, a Spanish Jesuit who dedicated his life to helping the poor and marginalized). The school, with an eye toward students of limited financial means, would offer a two-year associate degree. Students would attend classes 40 weeks out of the year, three to four days per week, and each class would be eight weeks in duration, followed by a two-week break. The ongoing nature of classes without an extended summer break would help keep students engaged.

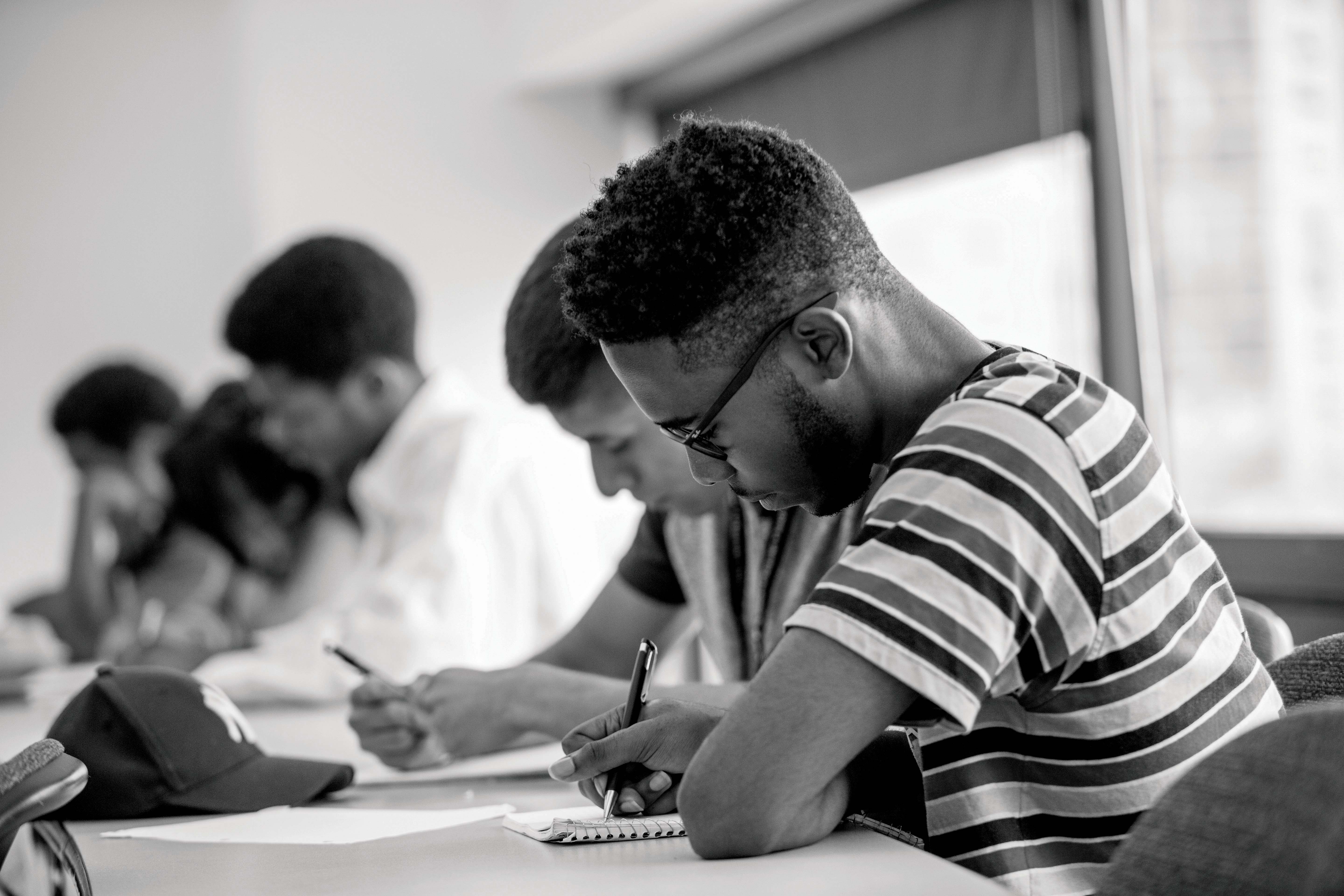

“If they’re off, they’re less likely to come back,” Katsouros says. Class sizes would also be small, with fewer than 30 students, to eliminate disconnect between the students and faculty.

Arrupe students arrive at their first day of class at Loyola University Chicago’s downtown campus.

The goal is for students to graduate with little or no debt. They could live at home, commute to school, and be encouraged to work part-time jobs to offset tuition costs and personal expenses. Students are required to file a Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA) and are expected to receive other aids and grants, which brings the per-year tuition cost down to approximately $2,000 per year. (That is versus about $12,500 for the 2015–2016 academic year, without assistance.)

Integral to the creation of Arrupe was an open and available building, Maguire Hall, at Loyola’s downtown campus near Chicago’s renowned “Magnificent Mile.” Here Arrupe’s classrooms, study halls, and offices could be housed in one place.

Recruitment for the inaugural year of this unusual school was as simple as Garanzini using his connections with principals of Chicago-area private, public, and charter high schools. The interest was immediate and strong—a “buzz,” Katsouros says of the grassroots effort. Katsouros also used his connections with the network of religious and secular high schools in the area.

Once recruited, senior students met with the two-person Arrupe admissions team that visited high schools to trumpet the school and explain the application process. Arrupe’s first-year class consists of 159 students, slightly more female (58 percent) than male.

Bringing faculty on board was not a burden. Interest was boosted by the model’s focus on teaching and advising (and not requiring instructors to publish). The faculty serves as advisers to 20 students and sets aside at least 10 hours a week for office hours. “All [faculty] are really turned on by this program,” Katsouros says.

Philosophy professor B. Minerva Ahumada works with students in her Philosophy and Persons class.

Focused on student success

The other key component was addressing the question: How to help these students flourish? The answer was to build a strong support network of professionals—six full-time faculty (expected to grow), as well as a licensed social worker, two associate deans (of student success and of academics), and a career coordinator.

Recognizing that many Arrupe students face more roadblocks to success in terms of their personal lives—they might be helping support their families or facing a daunting commute to campus—this education model is tasked with addressing the whole person. Administrators and professors refer repeatedly to Arrupe’s integrated, holistic supports.

The fledgling school’s commitment to evolving methods of cultivating a climate of success is critical. Yolanda Golden ponders that every day. Golden is Arrupe’s associate dean of student success. She oversees the college’s career counseling strategy, keeping students academically and socially on course. This formally began in July, the month before Arrupe classes were in session, with the three-week Summer Enrichment Program (SEP), of which completion is mandatory for all students.

Besides a time to register for classes, meet the faculty, and learn how to maneuver through the hurdles of financial aid, the summer program includes a two-day retreat where students participate in team-building activities—such as a ropes course—that enable them to start building friendships with each other. The SEP isn’t just social. Students take courses in digital media and math and a workshop designed to help decision-making with regard to majors and career choices.

For Golden, a former adjunct professor who spent eight years as academic adviser coordinator for Loyola’s School of Social Work, bringing 159 students together in these first days allowed her to observe their social skills. “Pairing up 15 to 16 students in small groups can help us figure out which students work well together,” she says. Faculty is involved as well. Part of the admission process is an interview with a faculty member. That’s where the staff can identify traits like shyness and the need for support from an orientation leader.

The summer program also helps Golden assess the students from an academic perspective, because students don’t choose their classes for the first semester.

The credits earned in the two-year program award students with an associate degree in arts and humanities, business, or social and behavioral sciences. Those 61 credits are transferable through the college’s involvement in the Illinois Articulation Initiative (IAI) to more than 100 four-year Illinois universities. With an Arrupe degree, students can likely enter a four-year university as a junior. Arrupe counselors will “help with the transition. If they want to go to Loyola, financial aid will be available,” Golden says.

The families of students are encouraged to be involved as well, but this involvement is balanced in a way that, Arrupe administrators say, allows their sons and daughters to have room to “blossom.” “I think it’s going to be a game changer in higher ed,” says dean and executive director Katsouros.

Weeks after the first school year began, Loyola held a blessing ceremony for Arrupe in Maguire Hall. There students rubbed palms with Chicago Mayor Rahm Emanuel and Chicago Archbishop Blase Cupich. It was a feel-good moment but also a sign of the significance of this initiative.

Jontae Thomas attended the blessing. “I wasn’t as nervous as I thought I’d be,” he says, “but it was an exciting day for me and all Arrupe students.” Six hours per week, Thomas works in Arrupe’s Office of Admission. He hopes to attend a four-year university after he completes his associate degree at Arrupe. He hasn’t decided which four-year school, but he knows the end goal. “Professionally, I want to own my own business,” says Thomas, whose dream is to be an event planner. His outgoing personality serves him well for one of his duties in the admission office: working with incoming students who are considering applying to Arrupe for the 2016–2017 school year.

Students split up into groups during B. Minerva Ahumada’s class.

Offering hope

Arrupe student Sonia Raggs turned things around for herself when she was a senior at Josephinum Academy, a Catholic college-prep high school in Chicago. Raggs had an emotional crisis between her sophomore and junior years in high school that left her questioning her academic studies. She stopped applying herself in class. “I thought, ‘What’s the point of going to school when I can’t afford college and I won’t be able to get a good job?’ ” Raggs says.

But the reaction of someone important to her changed her attitude: “When my principal told my grandma there was a potential I wouldn’t graduate, and seeing her [grandma] cry,” recalls Raggs, who finished up her senior year on a positive note and is now happily settled into the Arrupe program. Her grandmother continues to be a huge influence on her ambition to succeed. “I want to be the generation in my family that goes to college, and I want to show my grandma that she raised an awesome young woman,” Raggs says.

Raggs is on the road to showing her grandmother just that. She says her goals are simple: “I want to graduate with a master’s degree in psychology. I want to become a therapist for children and adults. I want them to be able to tell me everything, to be safe, and to know that I will help them.”

The challenges faced by Arrupe students like Raggs should not define them, says associate dean Golden. It is one of the reasons for Arrupe’s intensive support system. “They’re gifted. We have students raising children, helping contribute to their family households, and still going to classes four days a week and maintaining their grades,” says Golden. “If that’s not dedication, I don’t know what is.”

Test-taking guidance, faculty support, and advising have helped Raggs transition to the demands of higher education. The study groups that Golden has observed coming out of the team-building exercises in summer orientation factor heavily into student life. Class scheduling and structure are arranged so that students stay on campus to complete their homework before tackling what is, according to Golden, on average at least an hour commute to school by train, bus, or a combination. “We all stop studying once in a while and give each other feedback,” Raggs says of her study group.

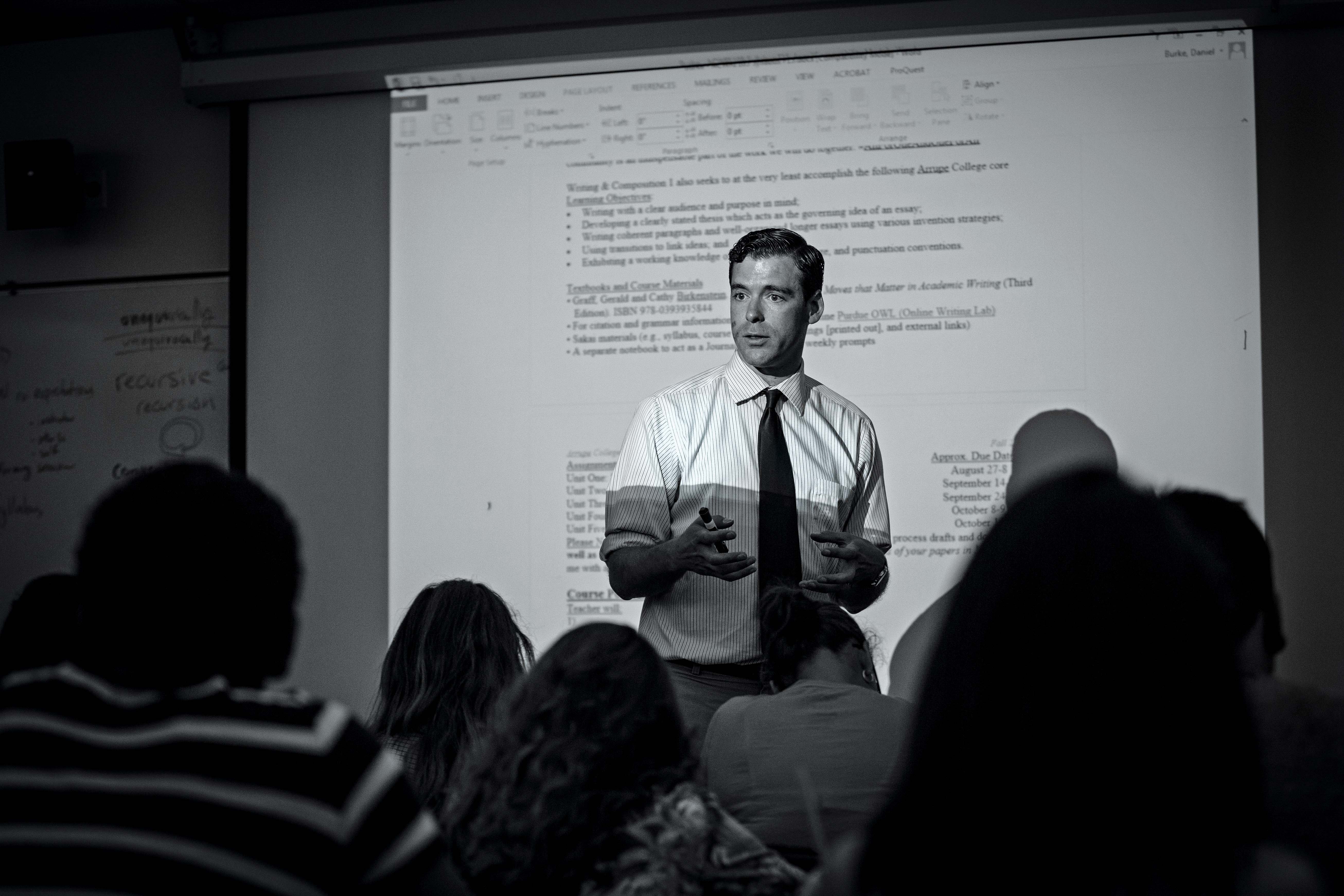

Both Raggs and Thomas appreciate the net of professional support that is also just a classroom away in Maguire Hall. English professor Daniel Burke was attracted to Arrupe’s teacher-adviser model. Burke, who teaches writing and composition, is not alone. “No one made it onto the faculty who wasn’t heavily, emotionally committed to the methodology,” he says.

Arrupe student Alonzo Bardney works during B. Minerva Ahumada’s Philosophy and Persons class.

Here, “holistic” is particularly applicable to the teaching style. The mind isn’t considered separate from the rest of the body. The compressed Arrupe semester of eight weeks (half of a typical college semester) also poses challenges for the student, hence the nurturing needed from teachers.

“It’s a constant struggle,” Burke concedes. “We want to do things that are comfortable like high school, but also like college. We talk a lot in our faculty meetings: ‘Are we holding hands too much?’ Support systems are there ideally if they need it. Not as a crutch.”

With respect to things like planning for the next semester and identifying and working toward goals, the students need the support. For the faculty to operate with the desired impact on students, a staff member, Jennifer Wozniak Boyle, associate dean for academic affairs, operates as their mentor.

Boyle not only hires the faculty and oversees their teaching assignments; she shapes the learning experience at Arrupe. She describes the academic advisers as mentors. Faculty are “modeling what it means to be an adviser or professional,” Boyle says. No one at Arrupe downplays the importance of a dedicated, appropriate student mentor.

When a student was losing ground in a first-year, first-semester statistics course and in danger of failing, the faculty “pulled together to help this student succeed,” says Boyle. The student pulled his weight to earn a C grade. “It’s a ‘startup’ so we’re doing everything, but that’s exciting,” and the staff worked as a team, she says.

Arrupe’s presence on Loyola Chicago’s downtown campus also presents a unique situation in which to help students mesh with the wider Loyola community. But the program’s intentionally small size has also facilitated the closeness of the Arrupe student body, although the staff would like to see that broaden to Loyola as a whole. “We don’t want them to feel siloed at Arrupe,” Burke says.

Integrating students into Loyola may well be an ongoing project. As that very first Arrupe class soldiers on through their first year, they grow comfortable with each other in the classroom setting. They’re starting to form social clubs that reflect their diverse interests. This is all to the delight of associate dean Golden. Digital media, theater, and “Dreamers and Allies” are among the clubs.

While the socialization evolution is normal in a collegiate setting, this is a singular boon in a higher-ed model in which language is also a concern. For 102 Arrupe students, English is not the first language spoken at home. Spanish is the majority for non-English speakers, but Polish and Russian are also in the mix.

B. Minerva Ahumada understands the scenario quite well. When the Arrupe philosophy lecturer came to the United States from her native Mexico to work on a master’s degree in philosophy, she didn’t have a mastery of English. Now with some ESL students in her classes, she says, “I think I identify with them a lot.” The language issue helps her “understand how to be a companion to the students inside and outside the classroom,” she says.

In her classroom, Ahumada tries to make philosophy relevant to students. Her style is not passive or simply feeding her students the day’s lesson. “I teach seminal texts (Aristotle, Plato), but I want them to see how it relates to their own lives,” she says. For one of her first-semester Arrupe courses, the class met in the morning twice a week for three hours.

The “struggle,” says Ahumada, a graduate of Loyola University Chicago, is “how best to use those three hours.” When the students are given an especially heavy reading assignment by a philosopher such as René Descartes, she has them meet in small groups while in class. Discussion helps. On one particular day, her students debated the notion of free will in a “philosophical experiment” created by their professor. When the students were able to get at the major debates within this concept without prompting from their professor, Ahumada says she was “beaming” with pride.

English professor Daniel Burke teaches Writing and Composition to Arrupe College students on the first day of class in Maguire Hall.

Ahumada is one of many staff members fueled by the innovation and the prospect of tweaking things as they go. English professor Daniel Burke talks about staff and students learning from each other and finding common ground.

“We’re not reinventing the wheel,” Burke says of his and his colleagues’ teaching styles. But Arrupe is about reinvention. When other models aren’t working, try something new. It’s a new idea in the Jesuit spirit of education and social justice.

This article appeared in the February 2016 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 81, No. 2, page 12–18).

All photos courtesy of Arrupe College of Loyola University Chicago/Natalie Battaglia

Add comment