Walking to Alabama's death chamber with his friend changed Father Sebastian Muccilli's life. He writes of his hope that Darrell Grayson's story may change our attitudes about the death penalty as well.

After comforting a death-row inmate in his final days, a priest has devoted himself to the cause of abolishing the death penalty.

Denis Staunton of The Irish Times described the 2007 execution of Darrell Grayson in Alabama's Holman Prison this way: "A guard drew back the curtain, and Grayson was lying just a few feet away, a lean, handsome man, draped in a white sheet and strapped to the gurney, his arms stretched out on black arm rests, almost in cruciform. Two drips attached to his right arm disappeared into a small square opening in the wall behind, next to a microphone hanging on a hook. Grayson saw Esther Brown and smiled and winked at her, flashing the peace sign with his fingers….

"Holman's warden, Grant Culliver, entered the chamber and approached the gurney. Culliver, an African American, is obliged by Alabama law to carry out all executions at the prison himself. ‘I look at it as part of the job,' he said in an interview two years ago. ‘The people of the state of Alabama, because of the way the laws are written, are as responsible as I am.'…

"As Culliver read the order of execution, Grayson's breathing quickened, his chest started to heave and, for the first time, a look of anguish crossed his face. When Culliver asked him if he wanted to make a statement, Grayson just said, ‘peace,' and again formed the peace sign with the fingers of each hand. The warden left the chamber to start the process of execution in a small room next door, so Grayson was now alone except for the chaplain, who remained standing rigidly in the corner. Grayson was smiling again, looking over at Brown, who mouthed the words, ‘I love you,' and he mouthed back, ‘I love you.'

"He exchanged a few words with the [chaplain], lay back, and waited. It was 6:04 p.m. and the deadly chemicals must now have been coursing through the canula into Grayson's vein, but nothing seemed to be happening. A minute later, Grayson looked up, smiled one more time, turned to his right…and closed his eyes."

For months I had lived with anxiety for a friend on death row in Alabama's Holman Prison. I continued hoping until the day of the execution that some intervention by Governor Bob Riley or the U.S. Supreme Court would delay his death to allow for DNA testing to prove Darrell's innocence.

Darrell was sentenced to death in 1982 at age 19, before DNA testing. He had been convicted of rape and murder by an all-white jury, defended by a state-appointed attorney whose professional focus was divorce and who acknowledged being unprepared and underfunded by the state to defend Darrell.

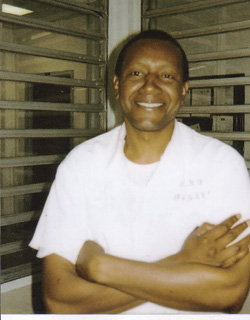

For four years I had been corresponding with Darrell and reading his published poetry. I had come to believe firmly in his innocence. I flew into Atmore, Alabama on July 24, 2007, two days before the execution to visit him.

As I approached the entrance to the prison, a guard in a lookout tower adjacent to the 12-foot-high double-fencing topped with razor wire shouted down to ask the reason for my presence. I waited while someone checked into whether I was approved for admission then entered through two imposing metal gates controlled by the tower guard. I then climbed the steps to the entrance of the prison.

I was frisked by a male guard; a woman guard took my photo ID, car key, and watch, and I signed in. I was finally admitted through an electronically controlled door by a guard I could see through a window in the opposite wall.

Darrell sat at the head of a long, metal table flanked by his sister, two nephews, a niece, and an attorney. As I approached, Darrell stood with a huge grin and his arms wide open in welcome. He introduced me to the others and asked me to sit immediately to his left. Two other attorneys arrived in the early afternoon. One of them said it was encouraging at this late date not to have heard from either the governor's office or from the Supreme Court regarding a delay for DNA testing.

Leaning over to speak with me privately, Darrell told me that a big regret was that he would be leaving his brothers on death row who had come to look upon him as their teacher, a vocation he had come to realize after a long depression. I reminded him that the title "rabbi" was attached to Jesus by his disciples. He related with satisfaction the admiration he enjoyed from his peers and brothers on death row and the notes of gratitude they had written him in the last few days expressing how their lives had been uplifted and changed by his encouragement and by what he wrote.

He told me how much he had come to depend on Esther Brown, his most trusted friend and loyal advocate for seven years. He had her to thank for bringing me into his life, he said. Then he reaffirmed his wish that I accompany him to the death chamber the next day. I agreed but did not allow myself to think of that scenario. At 4:30 p.m. the guards announced that it was time for visitors to leave.

On Thursday, July 26, I arrived at the prison at about 9:30 a.m. Only Esther was present in the visiting room with Darrell. It was through her devoted efforts that Darrell had come to terms with his innate talents, especially for poetry.

I had met Esther in 1967. She continues to take on her 74-year-old shoulders the burden of friendship and advocacy for death row inmates in Holman Prison. Esther and Darrell had worked tirelessly for a state moratorium on the death penalty through their in-house Project Hope for the End to the Death Penalty. Darrell was editor of its quarterly newsletter.

In the late morning Darrell's family members and the three lawyers trickled into the visitors' room. When the chaplain made an appearance, I successfully petitioned him at Darrell's urging to ask the warden to allow me to accompany Darrell into the death chamber. I dreaded the thought of that experience, but I wanted to fulfill Darrell's request and help ease the trauma that awaited him.

Darrell was not as calm as he had been the previous day. He looked tired. When it came time, at noon, for him to take leave of his family members and lawyers, Darrell, with his lanky arm around each of their shoulders, individually embraced his niece, nephews, and his sister last, conversing privately with each of them for the last time.

I left shortly thereafter to allow Esther and Darrell to be together, assuring Darrell of my return. Later that afternoon one of the lawyers showed me Governor Riley's statement on Darrell's case, which said that the governor had no intention of granting a stay of execution. I surmised that the Supreme Court had also refused to intervene. It was a rejection of the recommendation of the Innocence Project, which was willing to bear the expense of the DNA testing.

I returned to the prison at 4 p.m. Esther said her final good-bye to Darrell about a half-hour later. Within 15 minutes six burly guards arrived along with the chaplain. Darrell was handcuffed and directed out. The chaplain and I followed behind the guards.

We made our way through the prison precincts, past somber-faced, silent prisoners observing the last walk of a man so many of them had come to admire. We passed through three security sections until we reached the death cell, whose stark, white walls had no windows. About 15 yards away was the open door to the execution chamber. It was lit up as bright as an operating room but only for the grim task of destroying human life. I could see the gurney where Darrell would lie for his execution by lethal injection.

Darrell entered the cell, then asked for a cigarette from a guard, and reached for paper to begin writing his final thoughts to his sister and to Esther. While he was writing, I asked the chaplain about my request to be with Darrell in the death chamber. He said that the request was denied. I worried about how to tell Darrell.

Darrell asked for another cigarette and smoked it while completing the second letter and sealing the two envelopes. He asked the guards to allow me to enter. As I did so, he handed me the envelopes and asked that I give them both to Esther. "She'll know how to get this one to my sister."

Then he sat on his cot and motioned me to do the same, facing him. He asked me, close to a whisper, to stay in touch with Esther and to befriend Jeff Rieber, the death-row inmate who was succeeding him as editor of the newsletter and chairman of the board of Project Hope. Emphasizing the last request, he quickly noted Jeff's I.D. number on a slip of paper.

Conscious of time slipping away, I began to speak to Darrell of his example of courage and reminded him that he was still being a teacher-to me as well as the prison population. He listened with eyes closed. I explained how his body deserved a final anointing, that his spirit had been held in a body deserving of that respect.

I spoke the words accompanying the anointing of his forehead, eyes, ears, nose, mouth, and hands: "Through his holy anointing may God in love and mercy help you with the grace of the Holy Spirit to realize how much God loves you and the tenderness of God's affection for you."

I followed with a prayer for the dying and lastly invoked the Litany of the Saints, deliberately emphasizing certain personalities who reflected Darrell's gentle nature and integrity. When I had finished, he embraced me with an iron grip, and with his mouth near my right ear, he asked, "You'll be in there with me, right?"

When I told him the permission had been refused, he jumped off the cot and went to the entrance of the cell, rattling it and bringing the guards to attention. A guard got on the phone. I presume he called the warden. Still on the phone, the guard looked at Darrell and shook his head no.

I went to Darrell, led him back to the cot and told him that he didn't need me there, that his quiet dignity would see him through the ordeal and that I would be with him in spirit. He immediately composed himself, saying twice, "I'm not afraid." Within seconds, a guard called into the cell, "Grayson, you have five minutes." It was about 5:40 p.m.

Darrell took off his almost-new sneakers and gave them to one of the guards with the name of the prisoner-friend for whom they were intended. He gave me a smile and with silent dignity began his walk to execution in his stocking feet. I was immediately escorted in the opposite direction by a guard. The trek back to the prison entrance seemed endless.

I was with Darrell Grayson the last two days of his life, but it was the intensity of the last 30 minutes that is seared in my memory. I will always regret that Darrell's desire to have me with him in the death chamber was not honored.

As a priest I am proud that the church has publicly stipulated that every convicted death row inmate still has a right to life similar to the human fetus, and that we Christians have the honorable vocation to defend that adult human life from abortion in a prison death chamber. I'd like to see that challenge filter down to the parish pew-level of Catholic identity.

I returned home the day after the state of Alabama killed Darrell Grayson. The shock of that experience evolved first into grief and then into a passion to make my ministry an extension of Darrell's determined efforts to abolish the death penalty.

Project Hope stands as a bright memorial to Darrell Grayson and a reminder to me of the barbaric nature of a penal system intent on exacting revenge against those, innocent or not, incarcerated on death row. I want his hope for a less violent world to inspire others. We have the memory of his example and his poetry to teach us.

Add comment