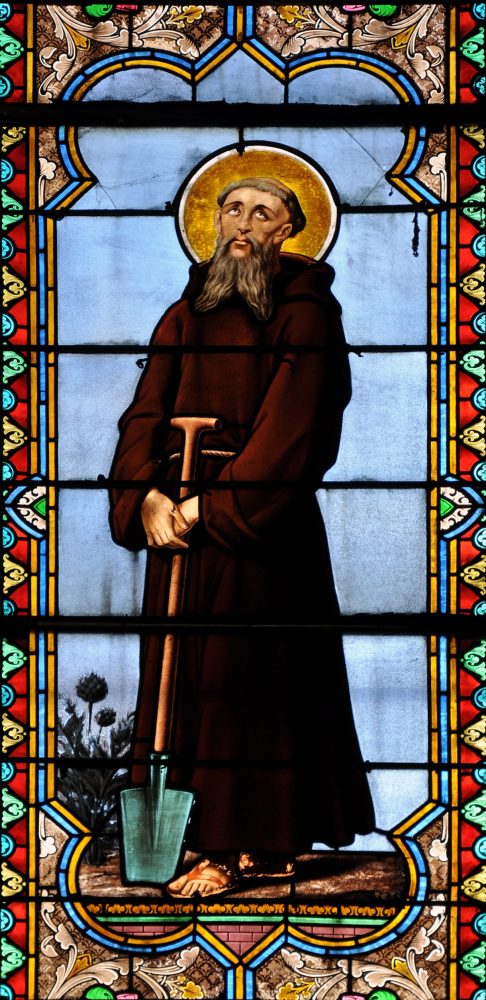

St. Fiacre

Born: 600 AD

Died: August 18, 670

Feast Day: August 30

Patron of: gardeners, herbalists, people with hemorrhoids and sexually transmitted diseases

Back in 1974, when she wrote The Saints of Ireland, Mary Ryan D’Arcy lamented the fact that even if you wanted to, you couldn’t buy a statue of St. Fiacre for your garden. Garden-sized Virgin Marys and St. Francises could be had by the truckload, but St. Fiacre—the patron saint of gardeners, no less—had been royally snubbed.

Well, Fiacre has finally made it to the big time. Last week I spotted him on the pages of the catalog of New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art. The catalog writer even thought enough to educate readers about the saint “who was noted for his vast gardens of healing herbs and vegetables ‘for to feed the poor.’ ” Seventy-five bucks and he’s yours.

Fiacre was born in Ireland in the seventh century and became a hermit in Kilkenny, but he soon left for France to seek even greater solitude for his prayer. When he arrived in the town of Meaux, he presented himself to Faro, the bishop of the district. Faro looked kindly on the foreigner, because as a child he and his family had been devoted to St. Columbanus, another Irish monk who founded many monasteries in France. The bishop gave Fiacre some of his own land in a forest on the banks of the Marne River—some of the most fertile soil in France. Legend has it that Faro offered Fiacre whatever land he could plough in one day. Fiacre, instead of finding the strongest team and horses and hitching them to the most mammoth plough he could find, turned up a modest parcel of earth with only the point of his staff. Now here was a fellow who took only what he needed.

Fiacre’s solitude didn’t last long. Pilgrims from all over began threading their way through the forest to find the monk and to learn about the Christian faith. The poor especially sought him out, but many of all classes came to seek his advice and prayers.

Faced with scores of homeless travelers, Fiacre soon found it necessary to build a hospice for his visitors and a small chapel as well. He employed his green thumb in producing food for the throngs, as well as herbs with which he healed the sick. Fiacre's kindness to the poor soon made him a legend in the district. While this lifestyle was obviously not quite what the monk had had in mind when he came to France, he made the best of it.

During his lifetime, Fiacre followed the custom of Irish monks by barring women from entering his hermitage and even his chapel. But after his death, he apparently reformed his opinion of women somewhat. Anne of Austria, who ruled France as queen alongside Louis XII, credited Fiacre with curing her husband’s serious illness; she also thanked the saint for hearing her prayers for an heir to the throne. When Anne made a pilgrimage on foot to show her gratitude, she respected the wishes of the long-dead Fiacre by offering her prayers outside the door of the chapel with the other pilgrims. (Of course, Butler's Lives of the Saints also reports the legend of the lady of Paris who, when visiting the shrine in 1620, claimed to be above the custom. She allegedly “became distracted upon the spot and never recovered her senses”!)

An extraordinary devotion to Fiacre flourished for centuries after his death among the people of France. St. Vincent de Paul had a special admiration for the saint because of Fiacre’s love for the poor.

Along with being the patron of gardeners and horticulturists, Fiacre is also the patron saint of French cabdrivers. But that’s a story for another day.

Originally published in Salt magazine, ©Claretian Publications.

Image: Wikimedia Commons