“They have taken the Lord out of the tomb, and we do not know where they have laid him.” • John 20:2b

Once a year, we as church stand in this same spot and look at—nothing. Apparently nothing, anyway, and yet hardly so. Because, after all, what’s to be found in the empty tomb of Jesus Christ?

Not bones, surely. Perhaps the redolent smell of oils and perfumes used in a still-recent embalming. Some burial cloths, once tenderly wound around a pierced and broken body, are now thoughtfully folded and set aside as if no longer needed.

And yet an abandoned tomb, this one anyway, is hardly void. This tomb that once held a body is now brimming with something else, something unanticipated and remarkable: hope.

What becomes clear to those of us who’ve lived through quite a few cycles of the church calendar is that our observance of these seasons keeps us as much as we keep them. Annually we ramble through Advent and Christmas, Lent and Easter and Pentecost to be ejected back into Ordinary Time until another cycle begins again.

At times we may surf these occasions casually or distractedly, but still they propel us forward through the years and our awareness of their richness deepens. Properly observed, all our liturgical seasons are revealed as seasons of hope. And our liturgical year, this simple scaffolding of time, faithfully outlines eternal aspects of human hope and divine fulfillment that serve as a barrier against the despair and disillusionment of a lifetime. Liturgical time gives us a beatific lens through which the far less orderly events of our personal histories, not to mention human history, can be viewed, contemplated, and understood.

Which is why every Easter we return to this spot again and again, as children, as adults, and finally as the elderly versions of ourselves, bowing down to peer into the darkness. Each year, we view the contents of the tomb of Jesus Christ to see for ourselves that this hallowed space is not hollow at all but full of hope. The older we get, the more we really need to know this. Death has no sting. It is not the victor.

This appreciation is important, since we stare down the specter of death every day of our lives. Death is in the news, embedded in our culture, celebrated in some forms of entertainment. The right to die and to kill is legislated and militarized and insisted upon across our society, and each one of these life issues is intertwined. We can’t, with integrity or any kind of honesty, defend one kind of killing and denounce another. The logic of such arguments unravels like so many burial cloths wrapped around vacant air. Our culture of death, as St. Pope John Paul II so frankly termed it, permeates modern life. Like it or not, until we reject the dance with death altogether in every form, we’ll be haunted by the testimony of fatal headlines every hour.

We have alternatives. As individuals and as church, we can choose ways of healing, caring, forgiving, and welcoming. We can love our Earth and refuse her further exploitation and contamination. We can learn what Jesus meant by loving our enemies in patient dialogue. We can mitigate the possibility of future enemies by making room for the migrant and investing in the world’s poor right now.

This is the pilgrim way of hope Pope Francis invites us to walk during this Jubilee Year. He opened that holy door for the whole church on Christmas Eve 2024 and urged us to pass through it, symbolically and intentionally.

Those of us who can’t make it to Rome this year or even to our local cathedral might have the opportunity to walk through a parish ceremonial door to ritualize our resolve to make hope our vocation this year. Me, I wrote the word HOPE in giant letters and put it up over my front door, reminding me that all of my comings and goings are opportunities to take the work of hope more seriously. Maybe my front door isn’t very grand or particularly holy. But if I don’t cultivate holy purposes in passing through this common door, no ritual passage will matter.

If this is the first you’re hearing about the holy year that’s already in motion these past four months, don’t panic or imagine you’ve missed out. Make hope your vocation today and going forward. Remember that hope isn’t an emotion we have to force or pretend into being.

If we’re going to talk about feelings, mine are all over the map most days. My personality tends naturally toward Eeyore, and optimism has always been a stretch for me. But hope is about placing confidence in God and not in all the worldly stuff: government, money, health, circumstances, or even the people we normally count on to have our backs or to bail us out of jams. Because other people are just like us—which means they, too, will prove disappointing sometimes.

When we place our hope for the future in God and rely on divine promises, things change. We make better decisions. The Osage Nation has a saying: “Strive to be a person who is never absent from an important act.” In this year of hope, I’ve been trying to live that out. I’m saying yes more than no. If someone needs me, I resist the urge to make up excuses to bow out. If there’s a gathering, I make an effort to be there. If someone asks to Zoom with me, even though it’s the fifth request this month, I refrain from rolling my eyes. If some wrong direction needs protesting, I mean to show up with my sign, my voice, or my vote.

I’ve spent a lifetime worrying about time. About not having enough of it to get my work done, to exercise, to learn what I need to know, or to do the things I really want to do. As a consequence, I’ve been very miserly about being available to people—a topic for confession across the decades.

But this year of hope requires me to reconsider that stance. I’m trying to trust that the Lord of time will ensure that there’s time enough for all that matters. We’re being directed, as pilgrims of hope, to be ambassadors of the peace and positivity most conversations could use more of. To be a hopeful presence requires, at the outset, actual presence. Dashing off an encouraging text may also help, but nothing beats being there.

On the Roman calendar of Jubilee observances this April, we honor the sick as well as health care workers (April 4–6), teenagers and youth (25–27), and people with disabilities (28–30). It’s good for parishes to recognize these groups at our liturgies or to supply opportunities for them to pass through the holy year door wherever it’s locally available. Fostering hope requires more than a ritual observance of who’s in our pews, of course. We honor each group on a particular day so as to become more aware of them and their needs in our communities every day.

In this Easter season of our realized hope, we celebrate the victory of the forces of life over the powers of death. There are as many ways to do this as there are unique parish communities facing their own local challenges: underfunded schools, hungry families, prison populations in want of visitors, isolated elders, high partisan grievance. Join a parish group addressing such concerns or start one. Bring hope to every hollowed place and make it hallowed.

This article also appears in the April 2025 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 90, No. 4, pages 47-49). Click here to subscribe to the magazine.

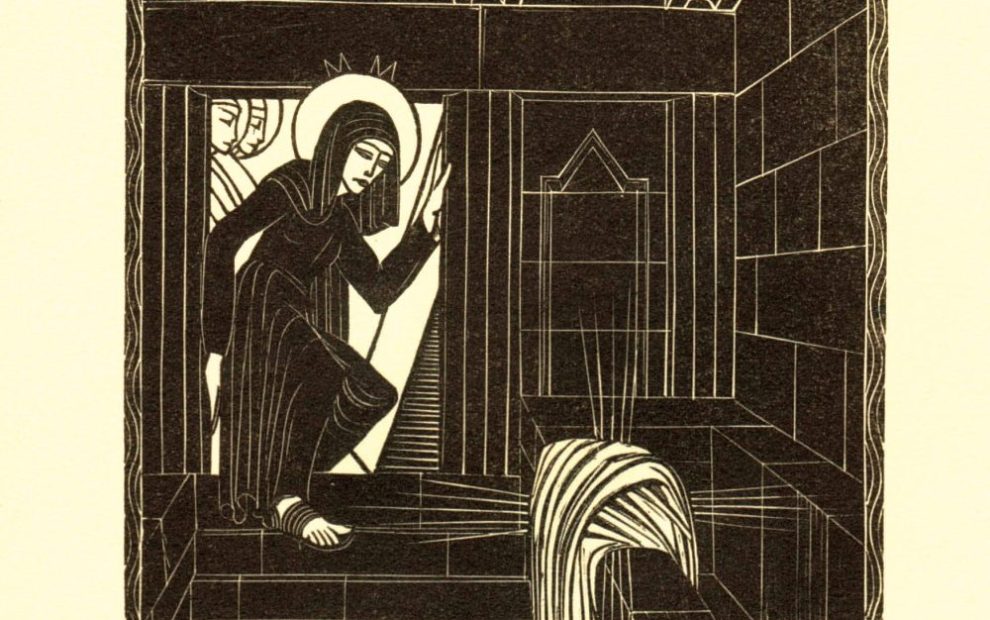

Image: The Resurrection, Eric Gill, 1917

Add comment