“Now during those days he went out to the mountain to pray, and he spent the night in prayer to God.” • (Luke 6:12)

You might say that it was Thérèse who introduced me to monasteries and the importance of silent retreats. Growing up in St. Therese parish in Philadelphia’s Mount Airy neighborhood, I knew Thérèse entered a monastery at the age of 15 and later died there at 24. In 1997, I visited her monastery in Lisieux, France to celebrate the 100th anniversary of her death.

As a young adult, monasteries continued to draw me in. When I entered seminary in September 1968, Frank Kelly, a classmate who hoped to enter a Trappist monastery, gave me a used copy of Thomas Merton’s The Seven Storey Mountain. I had never heard of the Trappists; this book marked the beginning of a lifelong love of Merton and the Trappists.

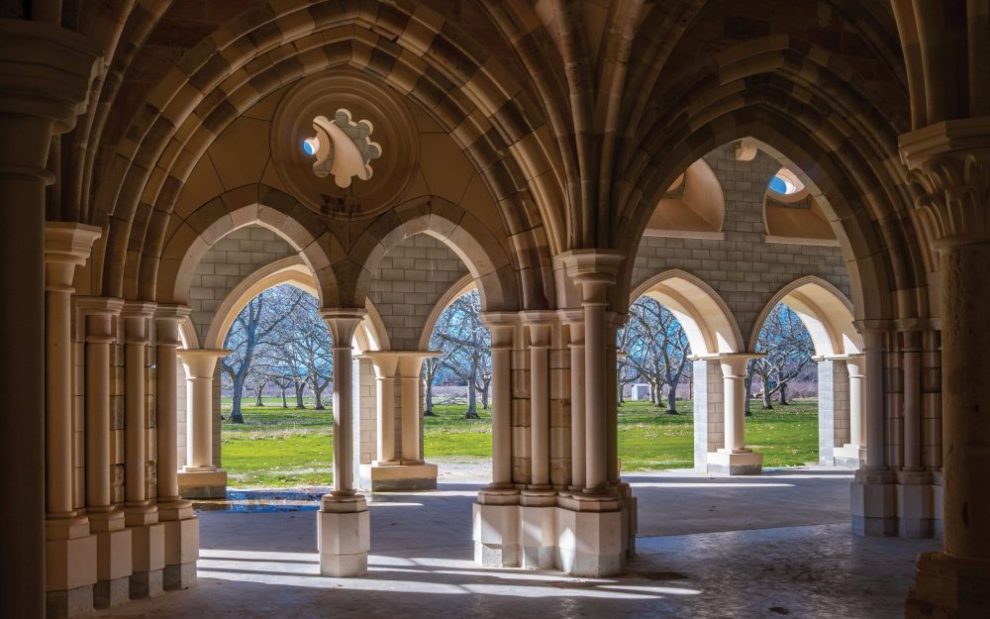

Early in his book, Merton speaks of traveling with his father through France. As they came to the shrine of St. Antonin, he wrote, “the church dominated the town, and each noon and evening sent forth the Angelus bells over the brown, ancient tiled roofs reminding people of the Mother of God who watched over them.” He continues on to say, “The whole landscape, unified by the church and its heavenward spire, seemed to say: this is the meaning of all created things: we have been made for no other purpose than that men may use us in raising themselves to God, and in proclaiming the glory of God.”

Reading further in the book, I realized that this ancient abbey with its spire was fundamental to Merton’s search for stability in his life. It represented a home where he could be “hidden in the secrecy of [God’s] protection.” Later in his life, upon first seeing Gethsemani, he noted the abbey’s “high familiar spire.”

After we finished college-seminary in 1972, four of us camped on the West Coast and, upon Frank’s suggestion, visited a few Trappist monasteries along the way. Our first was St. Benedict’s Monastery in Snowmass, Colorado, where the abbot made us breakfast. The second was the Abbey of Our Lady of the Holy Trinity in Huntsville, Utah. The third was the Abbey of Gethsemani near Bardstown, Kentucky, where Thomas Merton is buried.

After ordination, I went on archdiocesan retreats, but I found them to be too noisy and busy. Instead, I preferred to go on retreats at Trappist and Benedictine monasteries. Over the years, I also experienced a 30-day Ignatian retreat and retreats at various hermitages.

I’m writing this reflection from New Melleray Abbey, a Trappist monastery in Iowa, on the feast of St. Thérèse. With my favorite saint on hand and a Trappist monastery as the setting, I truly am in my happy space.

I have a spot in my room at home where I do spiritual reading every morning from 6:30 until 7:00 a.m. From 7:00 to 7:25, I sit in silence before a small wooden altar surrounded by icons and statues. At 7:30, we have morning Mass at the house. So why do I go to monasteries? Silence.

My mornings in my sacred place of prayer and reading help to make a place for silence in my daily routines, but I need more. I need a place dedicated to nurturing inner silence: a place outside of my home, outside of my place of work, outside of my normal life. I suppose that’s why I love to walk in nature. It gives me silence and time to listen. It is a place to let God speak. To feel the rustle of the Spirit gently moving and directing me.

I’m sure you need some silence in your lives and a place where you can be alone with God. I’m not a spiritual director, but I encourage you to seek out silence in your life. A quiet corner in a church can be a place for a silent retreat. An attic room. A path through a wooded area. An empty beach on a winter’s day. Somewhere God can speak.

This article also appears in the February 2025 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 90, No. 2, page 9). Click here to subscribe to the magazine.

Image: Wikimedia Commons/Frank Schulenburg

Add comment