Bludgeoning beats and raucous raps are the soundtrack to Franklinton Fridays, which take place in a trendy art district just east of downtown Columbus, Ohio. Local artists welcome guests to warehouse studios, while outside street vendors peddle everything from THC edibles to earrings.

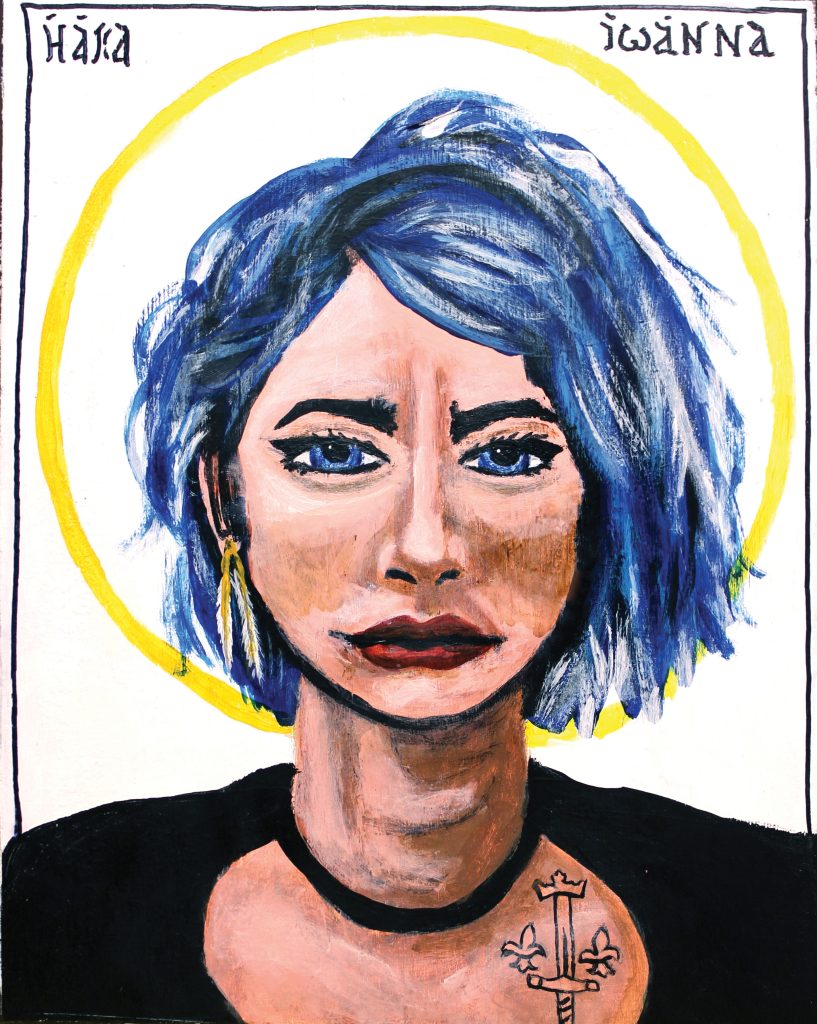

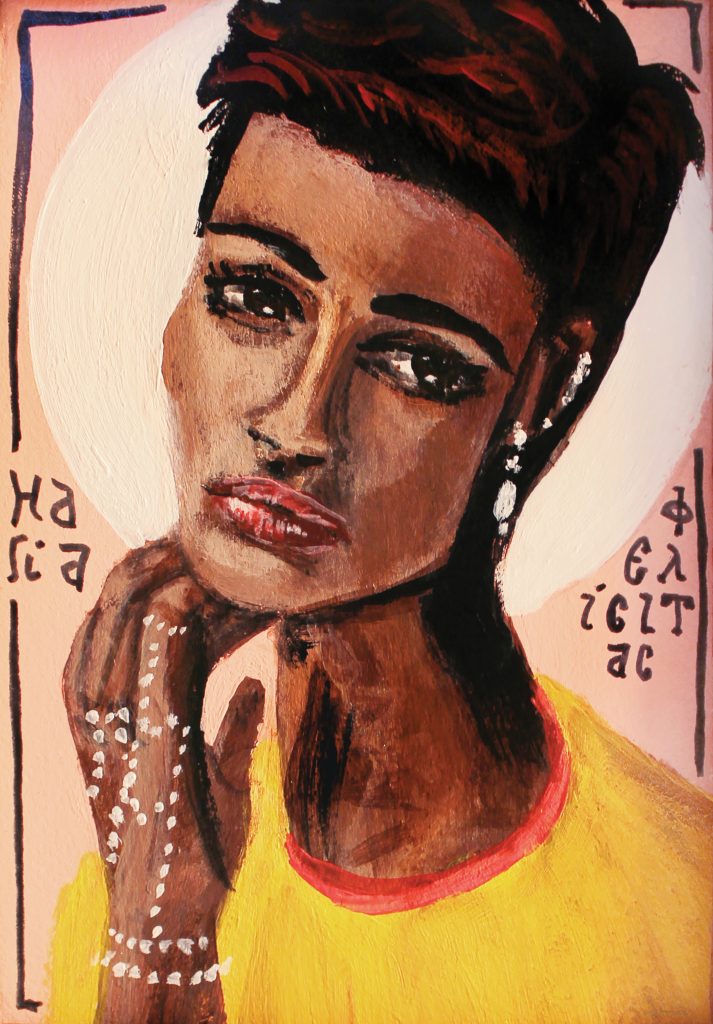

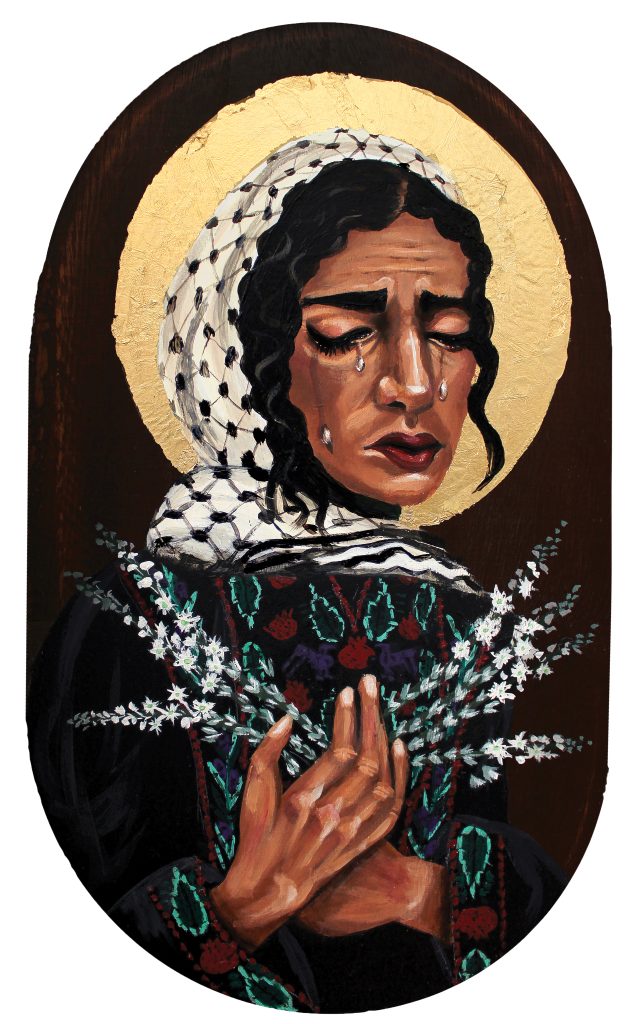

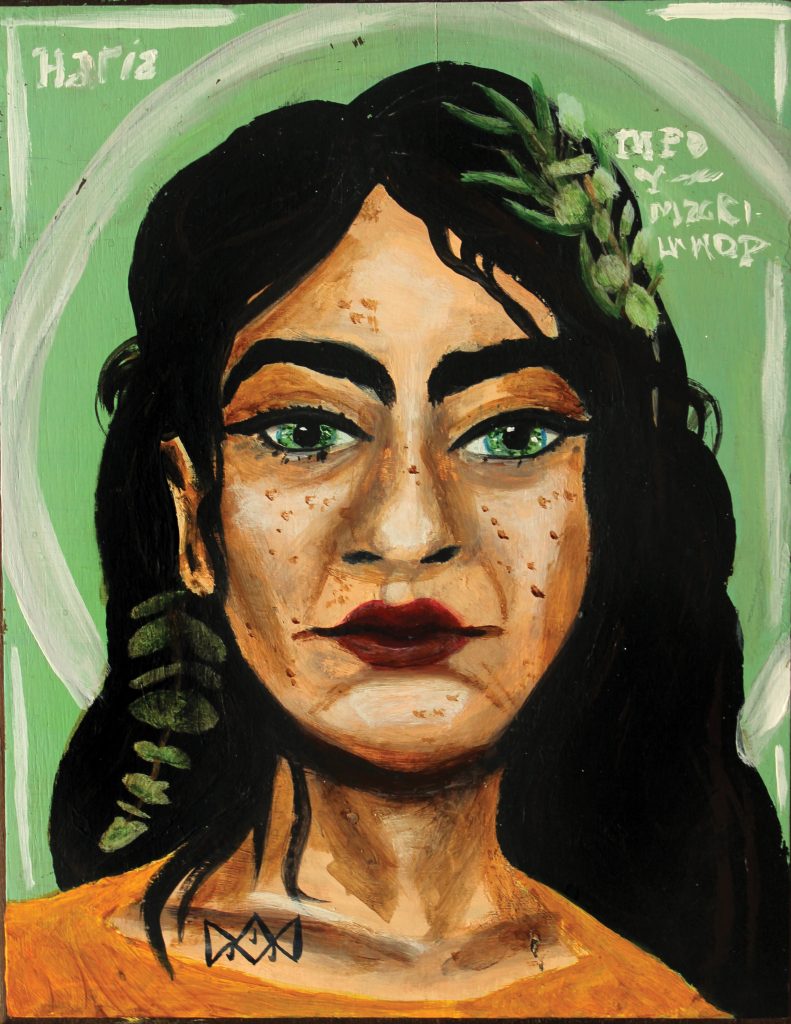

Patiently waiting behind a desk in one of the studios is an auburn-haired 27-year-old wearing a long, floral skirt. Only a few visitors straggle in, hesitantly, apparently killing time before their scheduled tarot card readings down the hall. They stay but a minute or two, unsure what to make of the pew-like benches facing a wall of more than 30 gold-haloed portraits on wood panels and a white-hot neon cross. They only briefly consider the faces that look back at them, some intense, some smiling, some in tears, and many with dreadlocks and tattooed arms. “I am happy to answer any questions you might have,” the proprietor says, as one couple beats a hasty retreat.

“Even if no one buys anything but they ask questions, I consider that a success,” artist Grace Morbitzer tells an observer.

Morbitzer, creator of the studio, author of a new book, and owner of an Instagram account all with the same name—The Modern Saints—is already a success by most standards. With more than 11,000 followers on Instagram, a calendar filled with national speaking engagements and workshops, and a steady stream of commissions, she has earned a living as a religious iconographer since 2021. Remarkably, her sole stock-in-trade is reimagined portraits of the church’s most holy men and women, originals painted in acrylic on reclaimed wood found in thrift stores and trash bins.

The popularity of her images, along with the social causes, original biographies, and prayers she posts on her website, The Modern Saints by Gracie, have found an eager audience, especially among Gen Zers and Millennials. They tell her they appreciate fresh definitions of saintliness and what it means to be a “good Catholic.” Morbitzer hopes the institutional church will take notice. “I feel like I have to stay in the church because I see a need. I want to be the change,” she says.

“The lives of the saints are always ready for a new generation to appreciate them, often finding elements in their stories that were overlooked or undervalued by previous generations,” says Jesuit Father James Martin. Martin is a contributor to the devotional The Modern Saints: Portraits and Reflections on the Saints (Convergent Books), a collection of essays by top Christian writers that Morbitzer edited and illustrated.

Feeling overlooked and undervalued is what first turned Morbitzer to the saints. In the book’s introduction, she tells of being “told hurtful things in the name of love” more than once as a 14-year student in Catholic schools and again in art college (but in her college classrooms, it was “Christianity-bashing sessions”). Finding her way as an adult in a new cultural environment was challenging, she writes. “I started to deconstruct and figure out what it was about my faith practice that I thought was worth keeping.”

What was worth keeping, she decided, were loving, accepting role models in her life, including parents who taught her not only Catholic traditions and values but also self-reliance, freethinking, and creativity.

Because she wanted inspiring décor for her college dorm room, Morbitzer thrifted wood plaques, on which she painted Divine Mercy, Mary, and her confirmation patroness, St. Genevieve. Unsure how to depict Christ’s clothing, she left his body unfinished, white gesso showing through.

“I left him in what basically looked like a white T-shirt,” she says. “The longer I sat with that, the more I realized that that itself was really interesting. Icons are meant to be contemplated, and contemplating him wearing something like the students around me, looking like the people that I know, was very powerful and brought up some new ideas for me.”

After posting the finished, “modern” portraits on Instagram, her feed was flooded with heart emojis, comments appreciating the refreshing relatability and humanity of her subjects, and requests for more.

“The idea of examining the Saints, I realized is exactly what I needed to do,” she writes in The Modern Saints. “Welcome the folks who’d been hurt by the Church—to see the hope that could come from learning about stories similar to theirs, but also to show members of the Church, the ones who had done the hurting, that they might in fact be casting out and abusing future Saints.”

Martin echoes this sentiment in his contribution to The Modern Saints. “Even the saints sometimes had trouble with their church,” he writes, “sometimes disagreeing with it and sometimes persecuted by it. But, despite all of this, they were always faithful to the church, as we are called to be. They understood that it was always flawed but always pointing us to holiness.”

As a schoolgirl, Morbitzer says she loved projects about the saints, but as an adult, her research into how holy people are portrayed in words and images forced a reckoning with inconsistencies, contradictions, and hidden agendas. She realized that many of the saints’ narratives were what Nigerian author Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie has called “single stories”—accounts that represent only one perspective, contributing to the creation of stereotypes.

“A lot of single stories have come down through the ages about one way to be a person of faith or one way to be a Christian,” Morbitzer says. Her art makes room for a multitude of stories, which in turn empower, dignify, and humanize the saints.

As she became more knowledgeable about church history, Morbitzer learned how single stories make saintly virtue seem unattainable by everyday people, perpetuating a culture of exclusion.

Most modern religious art shows the saints as white and European. Sixteenth-century Renaissance aesthetics, as well as even older traditions of religious iconography, have deeply influenced modern artists seeking to portray the saints. Eastern Orthodox officials strictly regulated artistic choices, including poses, period costumes, and appearances, all idealized to indicate the saints’ beatified state. “Some of them lived back in the year 300,” Morbitzer says.

“That’s such an intimidating gap in time from now until then. So I bring [their stories and images] into the present day.”

That’s why as her personal spirituality and her creative exploration deepened, she decided to keep some traditions of iconography and jettison others. For instance, she no longer selects her own subject matter, waiting instead for a commission, as ancient iconographers did.According to legend, St. Luke painted the world’s first icon of Mary, who, the story goes, “assigned him” to do so when she was still alive.

Like traditional icon artists, Morbitzer has come to honor the practice of her artwork as an expression of her faith. She begins each commission with weeks of preparation before picking up a paintbrush. Candles, incense, and prayers asking for her subject’s intercession accompany both historical research and cultural immersion.

Whenever possible, she consumes a saint’s native food and drink, creates a mood board of colors and images from their home country, listens to period music, and locates contemporary organizations with missions aligned with causes the saint served in life. When commissioned to paint Servant of God Thea Bowman, for example, Morbitzer listened to Southern Gospel music and discovered an organization called Catholics United for Black Lives, now hyperlinked to Bowman’s biography on Morbitzer’s website.

As she has acquired more knowledge of both church history and iconography, she decided to adapt and update other traditions. Moved by comments and reviews she receives from people who don’t typically see any saints who mirror their own experience, she is determined to push back on what she sees as inaccurate “whitewashing” of holy images and biographies. Instead, her portraits aim to reflect the actuality of her subjects’ age, race, and even physical imperfections, all for a higher purpose—to make holy people relatable.

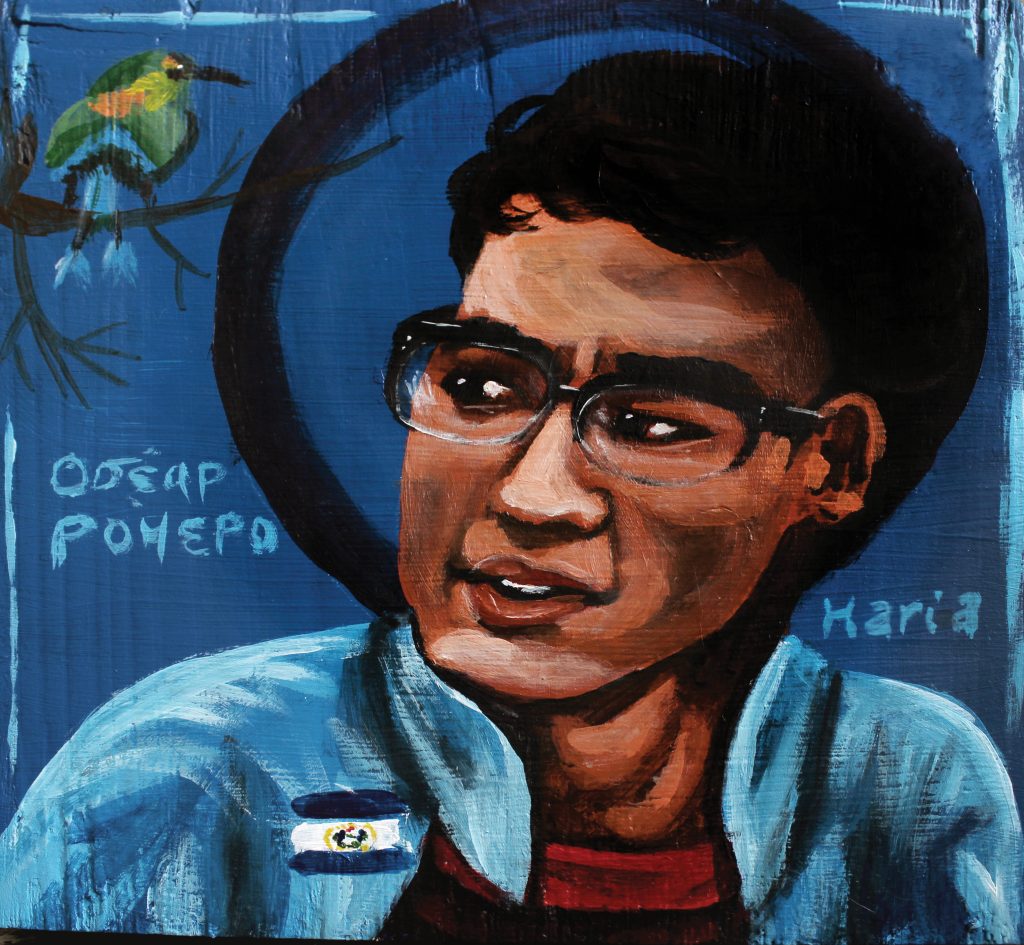

That is why her St. Augustine, born in Algiers, has a curly natural hairstyle and trim beard. North African St. Felicity is dark-skinned, while Australian St. Mary MacKillop is green-eyed and freckled. Rather than the traditional method of including symbols of a holy person’s attributes as objects, Morbitzer “writes” their stories with particular clothing, facial expressions, and sometimes human interactions in double portraits.

St. Joan of Arc’s shocking blue hair represents her boldness. Introspective St. Denis, with downcast eyes, hides his chin inside a black turtleneck. St. Francis’ arm is covered with a tree tattoo, while St. Thérèse of Lisieux’s roses are inked on her neck. The Virgin Mary and St. Elizabeth share an embrace, with one white halo crowning them together. Our Lady of Sorrows wears a Palestinian keffiyeh and weeps openly.

In other words, Morbitzer has revived the beating hearts of holy men and women, which she hopes will inspire believers to examine their own hearts for ways to make the universal church more accepting. Even before contributing to The Modern Saints book, writer Marcie Alvis Walker says she loved how Morbitzer’s saints look like her, or, as she joked during the Zoom launch of the book, look like “someone who would tour with Drake.”

Morbitzer firmly believes that everyone—regardless of their faith background—can benefit from having a “cheerleader in heaven.” And, she adds, we can all follow the examples of saints as role models. “Even if you wouldn’t consider yourself a saint as you are today, we all have that goal. Any of us can get there,” she says.

Cameron Bellm, whose essay about St. Óscar Romero is in the book, pulls from her shelf the iconic Picture Book of Saints (Catholic Book Publishing), originally published in the 1960s and only slightly updated since. “These images of God deserve better,” she says. “We all deserve better.”

As Bellm sees it, Morbitzer’s greatest contribution to building an inclusive church is her ability to draw a clear line from each saint’s era to the present day. “I think of [her saints] stomping their feet and saying, ‘Hey now! Let’s live out the gospels through reforming, through care for the sick and the poor, by calling out church leaders who are corrupt,’ ” she says. “There is not just one cookie-cutter response.”

The call to sainthood is universal, Morbitzer believes, and faith without works is not enough. That is why saint biographies on her website include links to causes each saint “might care about today,” she says. Because Archangel Raphael was said to have cured Tobit of blindness, for example, Morbitzer encourages her audience to contribute in some way to the American Foundation for the Blind. On social media, she commemorates feast days with aligned social justice fundraisers that might inspire followers to live out their faith values.

Morbitzer’s saint updates are not only visual. New hagiographies arise from her research, informed by her awareness of master narratives. Not only are her retellings unflinchingly honest about each saint’s struggles and brokenness, but they are also written in the vernacular of her generation. She writes on her website that Thérèse of Lisieux, for instance, “endured bullying in her convent” along with bodyshaming. Teresa of Ávila struggled with “toxic friendships.” The Roman soldier compatriots, Sts. Sergius and Bacchus, were like brothers and “have become known as patrons of the LGBTQ+ community.”

In response to followers’ persistent requests for holy cards featuring her portraits, Morbitzer also writes intercessory prayers. She says this is now her favorite part of the spiritual-creative process. She sees it as one way to love those wanting to feel heard and validated through consolation. She has even expanded some saints’ patronage in a spirit of inclusion.

“[Servant of God] Black Elk is only the patron of Indigenous people,” she says, “but I also made him patron of communities in transition.” The Modern Saints website even includes a quiz titled “Find Your Perfect Patron Saint.”

Morbitzer’s work is not without its critics, of course, ranging from anonymous trolls on social media to grandmothers complaining that Our Lady of Guadalupe’s dress is too short. At first, she struggled to reach art-buying patrons, being “too faith-based for arts spaces,” she says, “and too secular for faith-based spaces.” But just as her confidence in her process has grown, so has her resolve to stand in the breech with believers of all faiths—especially those in the margins. With humility, she invites everyone to lives of holiness and witness.

“[People] tell me to market myself more [on social media], but I don’t want to always be showing my face. I’m focusing on the diversity of these people. I don’t follow any of what’s trending. I am not willing to sell out,” Morbitzer says.

Instead, Morbitzer is at work on a second devotional, this time featuring saints even more on the margins, such as dog-faced St. Christopher and St. Drogo, a severely deformed man who is patron of unattractive people. Her most recent commissions include paintings for both Catholic and Protestant churches, poster illustrations about vocations for Catholic schools, and drawings for a “Building Catholic Futures” curriculum offered to Catholic clergy, lay ministers, and spiritual directors wishing to accompany LGBTQ+ Catholics. “She has a vision of a church that anyone could walk into and be at home,” says Eve Tushnet, the cofounder of “Building Catholic Futures.” “I love that.”

But when it comes to finding a faith home outside her art studio, Morbitzer says she is still searching. She has visited several parishes in her diocese, hoping to to find one upholding the same standards of diversity, acceptance, and expression of Christ’s teachings as she strives for in her artwork.

“Something that had started bothering me about Mass when I was going was just hearing from the same priest all the time,” she says. “Never having any other opinions or backgrounds heard from, no outreach groups or programs where I heard acceptance, you know?”

That is why, she reluctantly admits, she no longer attends Mass regularly. But, she adds, she hopes to return. She and her husband are new homeowners in her diocese’s oldest parish neighborhood, one with an active ministry to the neighborhood’s poor. “I want to have a home in this space and feel like it’s mine,” says Morbitzer.

Multiple studies confirm a similar and growing disconnect with the Mass among Catholics. A 2023 Pew Research survey found that only 3 out of 10 U.S. Catholics (28 percent) say they attend Mass weekly or more often. Larger shares of Catholics say they pray daily (52 percent) and say religion is very important in their life (46 percent).

Kaya Oakes, a Catholic journalist and author of The Nones Are Alright: A New Generation of Believers, Seekers, and Those in Between (Orbis Books), finds that young adult Catholics such as Morbitzer are increasingly content with a more cultural and less ritual-based faith, turning to service projects and informal fellowships for the connections they crave.

“Post pandemic and given the increasing number of people who consider themselves to be nones, spiritual but not religious, or ‘Catholic attracted,’ etc., this is going to be the new normal for most churches, not just Catholic ones,” Oakes says.

Morbitzer is convinced that the saints—past, present, and future—are exactly the Catholic ambassadors needed to reverse this trend. She thinks, for example, more Sunday homilies could present saints as examples of lived faith despite struggle, even if feast days and memorials fall on other days of the week.

“We’re all called to be saints, using the gifts we have to make our world a better place,” Morbitzer recently told an audience at a local arts center. “The saints are our role models. We have a [responsibility] to become role models for the future generations. That should be our goal.”

Back in the Modern Saints studio, a young couple thumbs through a collection of Morbitzer’s holy cards, picking and purchasing more than one. They enthusiastically tell the artist they are fans of both her book and the saints.

“We love to read the stories because we didn’t grow up as Catholic,” says Lauren Burns. “We didn’t know them.”

“We were drawn to the fact they are not all white European men,” adds her husband, Andy, assistant pastor at a nearby United Methodist congregation.

“But most of all,” Burns says, “we like the way she writes the intentions and the descriptions, because she is reimagining ordinary people as holy.”

On Franklinton Friday in Columbus, Ohio, the loud music eventually fades. As open house hours draw to a close, Morbitzer takes stock. She sold a few prints and a handful of holy cards, but more important, she spent time “being the change”—being the church at its best: open to encounter, accepting of others, and above all, loving.

“That is why I will never give up this project entirely,” she says. “It’s so humbling. To the saints, I am so grateful.”

This article also appears in the February 2025 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 90, No. 2, pages 10-15). Click here to subscribe to the magazine.

All art by Grace Morbitzer

Add comment