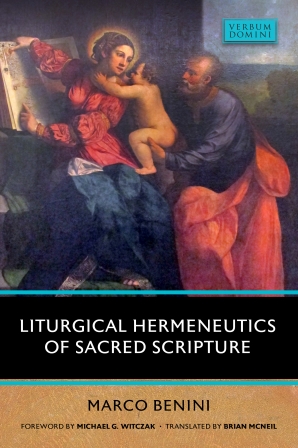

In Liturgical Hermeneutics of Sacred Scripture (Catholic University of America Press, 2023), Marco Benini discusses how liturgy allows the community to celebrate the stories told in scripture. This landmark volume, originally published in German in 2020 and translated by Brian McNeil, has three main sections. The first examines scripture’s role in liturgy, the second explores how liturgy gives meaning to biblical texts, and the third offers important insights on liturgical approaches to the Bible.

Throughout the book, Benini discusses liturgy as an act of remembrance (anamnesis), allowing believers to experience and participate in the work of God. One overarching theme is that the proclamation of scripture in liturgy makes present God’s saving work through Jesus Christ. When the worshipping community sings the responsorial psalm or listens to the homily, they connect their daily lives with the biblical texts. Other forms of prayer, like the Divine Office, transport the community into an encounter with God through biblical stories.

I appreciate Benini’s discussion of the revelation of God in scripture as the content of Christian prayer; scripture, as a source of piety and devotion, makes an anamnetic experience possible. Benini observes that scripture and liturgy “permeate and strengthen each other” through a dialogue of performance in the context of worship. Through liturgy, the words of scripture are transformed into an experience of union with the divine, so biblical stories of God’s presence in the world create a sense of personal connection. “Scripture is an event of revelation,” Benini writes, and “liturgy is a dialogical event of encounter.” This dyadic relationship between scripture and the liturgy reflects the character of the relationship between God and the community.

Benini offers a deeper appreciation for some of the Greek words in scripture, including καταβαίνω (katabaínō), which means “to move downward or climb down,” and αναβαίνω (anabainō), which indicates upward movement. In the Christian scriptures’ narratives, these terms often describe people going up to Jerusalem and then down again, with their movement’s apex at the Temple Mount. Geographically, travel to and from Jerusalem involves an up-and-down movement into and out of the city or the Temple Mount. In the third passion prediction in Mark’s gospel, for example, Jesus and his followers are going up (αναβαίνω) to Jerusalem. The story of the Good Samaritan begins with “a man was going down [καταβαίνω] from Jerusalem to Jericho.”

In Judaism, Jerusalem is the place of God’s presence; Mount Zion is the city of the living God. Based on this, Benini argues that “katabanic” liturgy indicates an encounter between God and the worshipping community, especially in the proclamation of the word. Meanwhile, the “anabatic” provides the background for prayer and hymns that invite the community to an active response and participation. The katabatic and anabatic senses of liturgy do not involve physical action but rather an invitation to spiritual movement within the sacred space of divine encounter.

The lectionary never includes some Bible passages, because excerpts for liturgical celebrations come from a “pool” of scripture. Choosing sacred texts for liturgical celebration is part of the liturgical committee’s overall hermeneutical disposition. Benini writes that “liturgy itself functions as an interpreter of Scripture, by means of the order of reading that establishes an intertextual communication between various biblical texts.”

This approach to scripture entails looking at passages from the Hebrew Bible in relationship with the Christian scriptures, as well as with the church’s liturgy. When Psalm 24, for instance, which is often used as a responsorial psalm in the liturgical ritual of several solemnities, appears in the liturgy of the Blessed Virgin Mary, it celebrates her as the one “who received blessing from the Lord, and vindication from the God of her salvation.” She is the “gate through which the King of Glory makes his entrance into the world.” But when this same passage is used during the celebration of the Presentation of our Lord, the “gate” recalls Jerusalem’s temple gates. Psalm 24 is also used as the entrance antiphon for Palm Sunday celebrations, and now, the intertextual hermeneutic envisions Jesus as the one who enters Jerusalem as the “King of Glory.” Then, when the church celebrates the Solemnity of All Saints, Psalm 24 links with the Revelation vision of the 144,000 from all nations, races, and peoples: “Lord, this is the people that longs to see your face.”

Benini recognizes the challenges of intertextual hermeneutics in the context of liturgical celebrations, admitting that the “external framework determines the hermeneutics lens of the functions and the principle of selection of texts of Scripture in liturgy.” The liturgical celebration of the church, the situation of the celebration, and the rituals of the community “have repercussions on the understanding of the biblical words.”

Benini’s work should be required reading for seminary courses on scripture and liturgy. His book invites pastors to find profound meaning in the rubrics of liturgy, via the texts of sacred scripture, so that the interaction between human and divine may come alive and be strengthened during public rituals of devotion.

Unsplash/Rod Long

Add comment