For our Sounding Board column, U.S. Catholic asks authors to argue one side of a many-sided issue of importance to Catholics around the country. We also invite readers to submit their responses to these opinion essays—whether agreement or disagreement—in the survey that follows. A selection of the survey results appear below, as well as in the August 2024 issue of U.S. Catholic. You can participate in our current survey here.

The year I started high school, my family moved to a small town that had one Catholic community. The old parish church had a ramp out front, but once we got inside, my younger brother’s wheelchair couldn’t fit down the aisles. Our problem was solved, however, when we learned the parish had just built a brand-new complex on the outskirts of town. Its double doors were wide, there were no stairs, and the gathering space had rows of folding chairs that could easily be moved to accommodate a wheelchair. The sanctuary even had a ramp. A year or two later, the community added projectors to provide visual aids alongside the music and readings. Finally, an accessible church!

But then I noticed a troubling pattern in the comments directed at our family:

“I look forward to seeing what Matthew will be like in heaven.”

“Your mother is a saint for saying yes to this cross.”

“It’s so interesting to see how past mistakes in a family tree manifest today.”

“I pray for Matthew every day that he might be healed.”

These comments frightened me. People at our church clearly thought Matthew’s disabilities were an unfortunate mistake that should be shed, if not in this life, then the next. But who would Matthew be without his disability? Did God really want Matthew to be different? Had someone in our family done something to cause this?

Even at otherwise accessible churches that comply with the Americans with Disabilities Act, disabled Catholics are still being told they don’t belong as they are. What good is an accessible seat if the person occupying it hears from the pulpit that their disability is a sin, metaphorically or otherwise? If we truly believe all are welcome, we need to do more than just let a person live or make sure a person gets inside: We must uproot poisonous assumptions about disability from our interpretations of scripture and sacrament.

Often, an able-bodied person’s first exposure to disability is with a loved one or during a service experience. A personal relationship with a person with disabilities is the best place to start, and it can be a learning experience.

However, all human beings are more than what they teach us about ourselves. Each person, regardless of ability, has full, complex emotions with likes, dislikes, and needs that include the desires for education, work, and intimacy. Few of us would admit to thinking of disabled people as less than human—but when we make assumptions about what a disabled person can or cannot do, or when we only interact with disabled people in the context of service and not in mutual relationships, we are still viewing “us” as more and “them” as less. This shows up in parishes as ministering to rather than with.

But disability is normal. If we are lucky to live long lives, all of us will experience disability. Whether by illness, injury, pregnancy, or aging, we will all experience debilitating changes that may permanently alter our bodies.

If we recognized that all bodies change, then access wouldn’t be an issue. All curbs would have cuts. We would standardize health care. We would allow for parental leave. We would relinquish our rigid obsession with “doing.” Unfortunately, our human hubris and cultural standards of beauty and productivity tell us that permanent, unchanging health is the norm, and everything else is an aberration.

Because we fear physical changes, we assume a life of disability equals a life of suffering. But disabled people experience joy. Certainly, a disability that brings physical pain can cause deep suffering, and some people may want to change their bodies to alleviate that pain; this is the “medical model” of disability. But much of disability’s suffering comes from exclusion rather than any physical issue. (This is the “social model” of disability.)

Many Christians interpret the healing narratives in scripture from a place of fear. When we see Jesus healing the deaf, blind, and paralyzed, we believe he is fixing “problems” and eliminating physical suffering. But, in the context of his other encounters, we see Jesus is primarily concerned with social outcasts who are separated from their communities because of their identities. By giving attention to a disabled person—and removing the obstacle to social belonging—Jesus returns each marginalized person back to their community. He blends the social and medical models.

Our own vision of the sacraments, however, is often stuck in the medical model. For instance, my brother Matthew has had dozens of operations over the course of his life, and before most of them, he received the anointing of the sick. In those moments, our family couldn’t help but recall the old name for this sacrament: the last rites. Our whole family could have used pastoral accompaniment during this scary time.

Instead, each time, the rite felt transactional. We give the faith, the priest gives the chrism, God gives the miracle, then we go on our way. Every time, I was disappointed when no miracle occurred. Then, I was embarrassed. I also couldn’t shake the feeling that the parishioners gathered around the holy spectacle were leaving disappointed: They had hoped to see Matthew “pick up his mat and walk” (John 5:8).

The anointing of the sick is often taught as inherently multifaceted: Some healing is immediate, some is delayed; some is physical, some is spiritual. This is all true. But the expectations we bring to the sacrament can be just as problematic as our misinterpretation of the healing scriptures. By focusing too much on the perceived “badness” of illness, we are once again missing Jesus’ social priority and even limiting God’s miraculous ability.

What if we approached these situations differently? Instead of praying to be magically conventionally healthy, might we pray to be rested, at peace, and prepared for postoperative healing? Could the anointing of the sick remind the broader community of their responsibility to support a sick person? Might the sacraments invite us to meditate on the everlasting presence of Jesus in exactly the bodies we have?

In the story of the man born blind, Jesus gives a reason for disability: “It is so the works of God might be made visible through him” (John 9:3). We tend to assume this means the literal healing God provided. But again, that’s an interpretation we place upon the text. Couldn’t it be that this blind man went on to live an extraordinary life? Might the “works of God” be that blind man’s own contributions?

In other healing stories, we hear Jesus explicitly tell the healed not to highlight the literal healing that has happened. And in multiple passages, Jesus asks the disabled person what they want Jesus to do. Jesus does not always assume a disabled person wants literal healing. Why should we?

In The Disabled God (Abingdon Press), theologian Nancy Eiesland focuses on the wounds of Christ, which are retained after the resurrection. If disability were not part of the kingdom of God, why would Jesus’ wounds linger? His wounds were key to his disciples’ recognition of him.

We know Jesus by his body, and this is also how we know one another. At my family’s parish, all it took was ministry leaders getting to know Matthew deeply to slowly change their hearts. These same leaders later approached my mother and asked her if they could help Matthew receive the sacraments.

The harmful comments people had made were, at their core, well-meaning attempts to accommodate into our tradition what society says about bodies. For centuries, despite his own insistence on the opposite, Jesus’ healing miracles have been interpreted as him saving the plagued from sin. Lines like “falling on deaf ears” and “I once was blind but now I see” equate disability with lack of faith, leading to the false belief that someone can pray away disability. This isn’t church teaching; it’s the modern obsession with picking ourselves up by our bootstraps, the belief that if you just work hard enough, pray hard enough, and have enough worldly success, you can fix yourself.

Jesus’ example gives the church a way to combat harmful cultural expectations around bodies by changing the way we talk about them. Far more than any ramp or doorway, rejecting old narratives will create more room for everyone, including disabled Catholics.

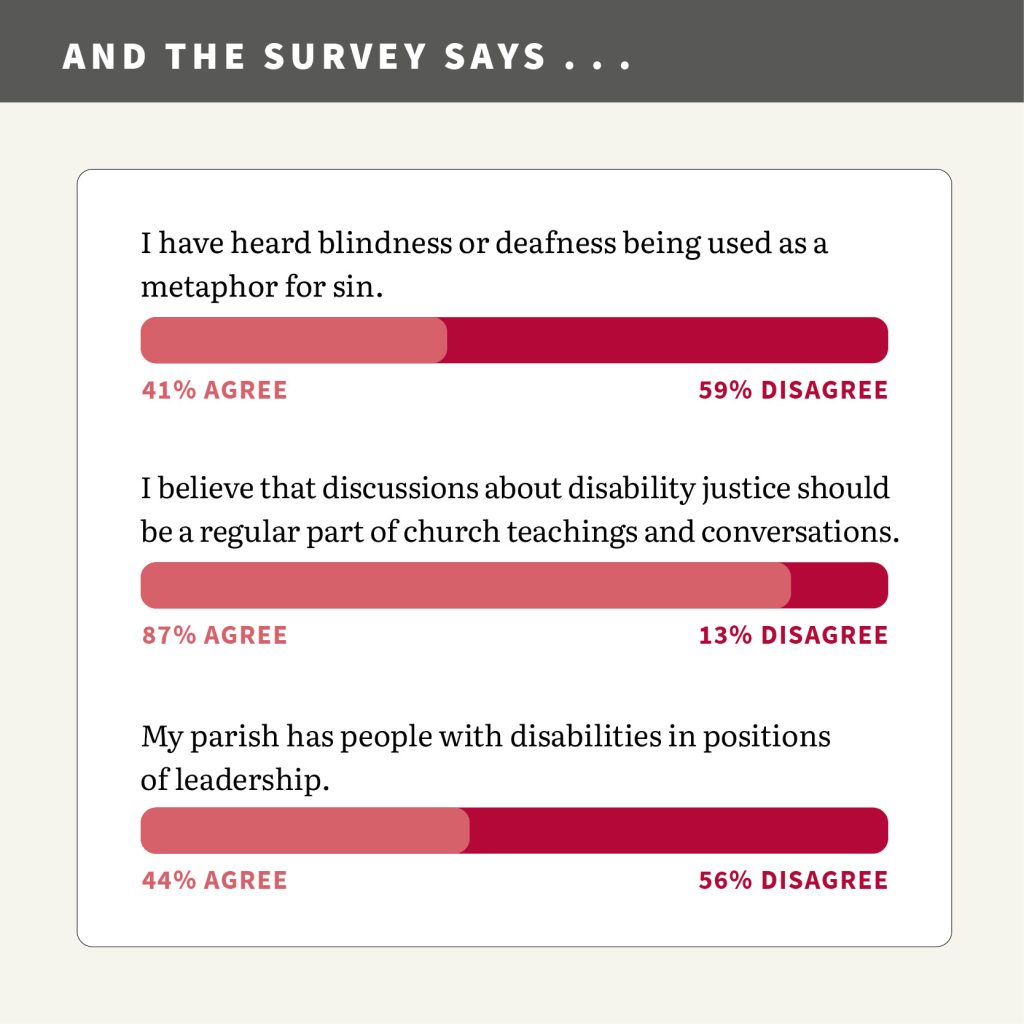

Results are based on survey responses from 61 uscatholic.org users.

This article also appears in the August 2024 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 89, No. 8, pages 21-25). Click here to subscribe to the magazine.

Header image: Pexels/Marcus Aurelius

Add comment