At a recent fitness class, I saw a T-shirt slogan that stuck with me: “In a world where you can be anything, be kind.” While it may sound trite, often kindness is neither obvious nor easy. We must actively choose to be kind, and this can sometimes be quite difficult. As Pope Francis notes, “We need to acknowledge that we are constantly tempted to ignore others, especially the weak.” In our deeply divided society, the reminder to be kind is really a reminder to love our neighbor.

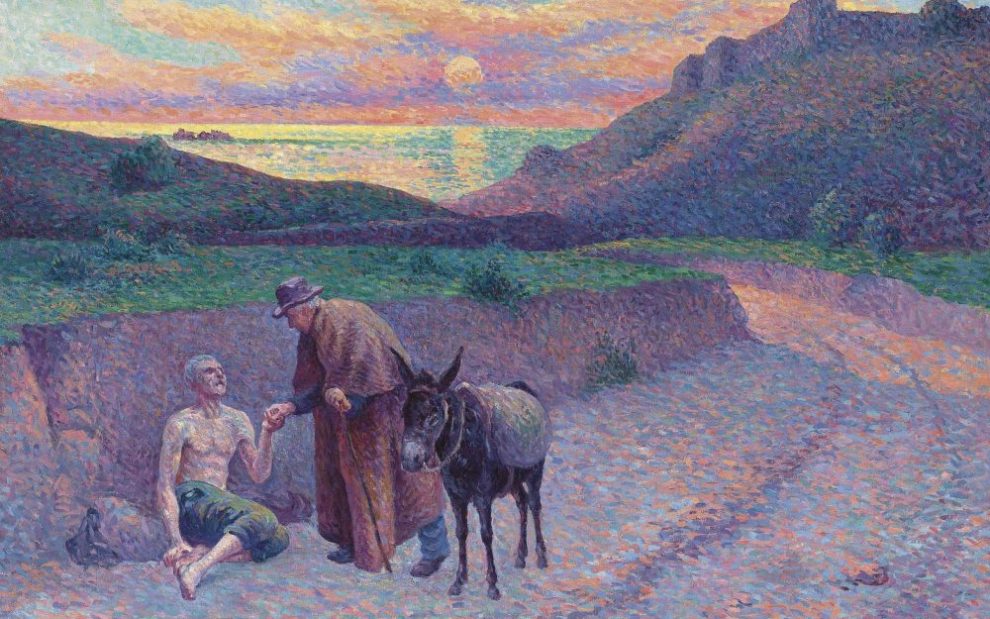

“Who is my neighbor?” A lawyer asks Jesus this simple yet provocative question in Luke’s gospel. Jesus tells the story of a wounded man left injured on the side of the road from Jerusalem to Jericho. The religious elites do not show kindness; they simply keep walking. But a Samaritan traveler, someone who would likely have been considered an enemy of both the wounded man and Jesus’ original audience, stops to provide aid. Scripture tells us he was “moved with compassion at the sight” (American Standard Version). Kindness or compassion begins in recognizing the common human dignity of our neighbor and propels us to act.

In Compassionate Respect (Paulist Press), Sister Margaret Farley argues that “compassion requires normative shaping.” When we are moved with compassion, she notes, we must ask, “What does compassion require?” Without that second step, compassion fails to truly be present.

This is particularly true in health care. Medical care teams can only provide effective medical treatment if it is done with an ethic of compassionate respect. Patients must always be recognized as people first. Addressing their needs requires taking into consideration their concrete symptoms but also their spiritual, familial, and cultural contexts.

“Compassion allows you to see reality,” says Pope Francis, for “compassion is like the lens of the heart: It allows us to take in and understand the true dimensions.” If we consider the parable of the Good Samaritan, we can see a model of this ethics of compassionate respect. In the story, the Samaritan did three things: poured wine over the man’s open wounds to disinfect them, poured oil to protect and soothe them, and brought the wounded man to an inn for further care. There is nothing abstract or ephemeral about the practice of compassion. It is concrete and practical.

The ethics of compassion is also a place of convergence in our pluralistic and often divided society. Over the last school year, I have been revising my theological ethics of health care course with help from Interfaith America. In their final exam essays, many of my students chose compassion for their interfaith essay topic. A central virtue in basically all religious traditions, an ethics of compassion can provide important common ground for discussion in a polarized world.

In Buddhism, distance from suffering does not mean distance from people who are sick or in pain. In fact, according to the Dalai Lama, compassion is a “deep inborn emotion and the source of happiness.” Prioritizing holistic care that included spiritual dimensions, early Buddhist monasteries served as hospices and infirmaries. It is easy to see common ground in this commitment to alleviate suffering and a sense of happiness in a life lived through love of neighbor.

For the Abrahamic traditions, the ultimate common reference point is God as creator and God’s own compassion. In “Towards an understanding of compassion from an Islamic perspective,” published in the Journal of Clinical Nursing, authors Jalal Alharbi and Lourance Al Hadid note that “among God’s own names that are recited repeatedly in every prayer are Rahman and Rahim (meaning compassionate and merciful).” The refrain to be compassionate as God is compassionate is interwoven within the three traditions’ instructions to believers on how to care for the sick, the poor, and all those who are suffering. According to the late Rabbi Jonathan Sacks, “Justice plus compassion equals tzedek, the first precondition of a decent society.”

Returning to the parable of the Good Samaritan, Pope Francis suggests it as a blueprint for rebuilding “our wounded world,” arguing that “Jesus’ parable summons us to rediscover our vocation as citizens of our respective nations and of the entire world, builders of a new social bond.” Perhaps in an ethics of compassion, we find a deep and nuanced invitation to live into our common humanity. And perhaps we will also find some common ground from which to build a world with more kindness.

This article also appears in the August 2024 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 89, No. 8, pages 40-41). Click here to subscribe to the magazine.

Image: The Good Samaritan, Maximilien Luce, oil on canvas, 1896

Add comment