In 1550, two Spanish priests were engaged in a heated public debate on a topic of significant moral importance: the rights of Indigenous peoples. Could the Indigenous people of the Americas be considered fully human, entitled to the same rights and protections as the Spaniards themselves?

On one side of the debate, arguing that they were less than human—and therefore that the Spanish empire’s treatment of them was justifiable—was Juan Ginés de Sepúlveda. On the opposing side was a defender of the Indigenous people who believed they were fully human and that attempts to subjugate them were morally repulsive.

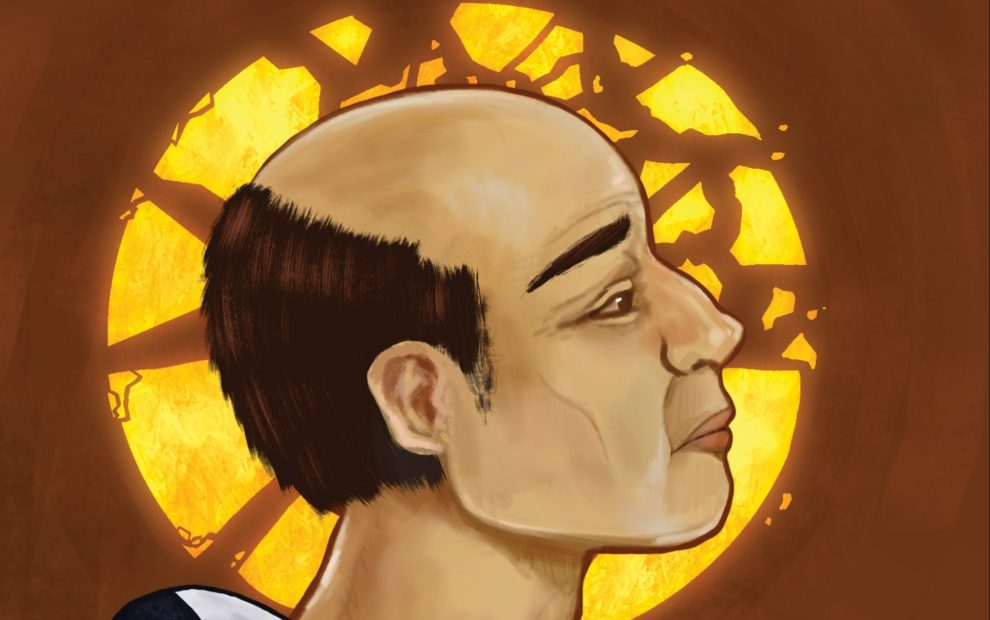

The defender of the Indigenous peoples was Servant of God Bartolomé de Las Casas. Las Casas argued that Indigenous people were worthy of rights simply because they were children of God.

Not much is known about Las Casas’ early life, only that he was born around 1484 in the city of Sevilla. His father, Pedro de Las Casas, accompanied Christopher Columbus on his second voyage, and upon their return in 1499, he brought a “gift” for his son: an Indigenous boy.

In 1502, Las Casas left Spain and settled on the island of Hispaniola (modern-day Haiti and the Dominican Republic), where he was a slave owner on an encomienda, a royal land grant. He took part in slave raids and military expeditions against the native population of Hispaniola.

A few years later, in 1506, Las Casas returned to Spain and then traveled to Rome, where he was ordained as a priest. When he returned to Hispaniola, he continued to benefit both financially and socially from Spanish imperialism.

Shortly after this, a group of Dominican friars arrived in Hispaniola. Appalled by the colonists’ abuse of the Indigenous people, the Dominicans were outspoken in their condemnation. In a particularly fiery sermon, one of the Dominicans preached: “Tell me by what right of justice do you hold these Indians in such a cruel and horrible servitude? . . . Why do you keep them so oppressed and exhausted. . . ?” The Dominicans refused to extend the Eucharist to slaveholders—including Las Casas. Las Casas and the other colonists complained to the king, who recalled the Dominicans to Spain.

During the next few years, Las Casas participated in Spain’s conquest of Cuba and took part in massacres and other atrocities committed against the Indigenous people. He later wrote: “I saw here cruelty on a scale no living being has ever seen or expects to see.”

Then, in 1514, as Las Casas was preparing for a homily, some verses from the Hebrew scriptures woke him up to his guilt. “If one sacrifices from what has been wrongfully obtained, the offering is blemished,” he read in the Book of Sirach. “Like one who kills a son before his father’s eyes is the man who offers a sacrifice from the property of the poor. The bread of the needy is the life of the poor; whoever deprives them of it is a man of blood. To take away a neighbor’s living is to murder him; to deprive an employee of his wages is to shed blood” (34:18–22). Las Casas recognized his own actions in the sins described in this passage. He became convinced that Spain’s treatment of Indigenous people was not only unjust but also a sin.

Las Casas’ conviction led to action. He freed the enslaved people who worked his land, he gave back the land to the native inhabitants, and he preached loudly and vehemently that the other colonists should follow his example. When his fellow Spaniards resisted, he decided to bring his new understanding to the king of Spain.

In the years that followed, Las Casas went back and forth across the Atlantic (10 times in all), working tirelessly to build a cooperative, peaceful form of colonialism. His efforts extended from Venezuela and Peru to Guatemala, Panama, Nicaragua, and Mexico. He faced harsh criticism from his fellow Europeans; harassment and massacres beset the Indigenous communities he tried to build. Discouraged and heartbroken, he still did not give up.

Las Casas dedicated his life to protecting Indigenous people, earning the title Protector de Indios (Protector of the Indians). In his seminal work Brevísima relación de la destrucción de las Indias (A Short Account of the Destruction of the Indies), he describes the atrocities the Spanish committed on Indigenous communities and argues for the native people’s inherent dignity:

The reader may ask himself if this is not cruelty and injustice of a kind so terrible that it beggars the imagination, and whether these poor people would not fare far better if they were entrusted to the devils in Hell than they do at the hands of the devils of the New World who masquerade as Christians.

Las Casas reminds his readers that God created Indigenous peoples, and he also notes that they are not a monolithic people but many diverse peoples. Additionally, he points out the inherent hypocrisy of conquistadors who claimed to follow Christ while harming God’s children; real Christians, Las Casas makes clear, would not commit such horrific acts.

Las Casas sought to introduce Christianity not by force but through dialogue. The church, he wrote, is enriched by all people, so all people should be embraced and respected. Thanks to his efforts, Pope Paul III issued Sublimis Deus (On the Enslavement and Evangelization of Indians) in 1537, stating that the native people of the Americas were rational beings who should be brought peacefully to the faith.

Unfortunately, Las Casas, in his fervor to protect Indigenous people, initially argued that enslaved Africans should replace native labor. But he quickly renounced this belief, too, and went on to write against all forms of slavery.

Las Casas’ actions are in stark contrast to the behaviors and beliefs of most Europeans during his lifetime. He was by no means perfect, and not all people of color today see him as a hero. After all, he supported imperialism, and he failed to respect and protect Indigenous culture and spiritual beliefs. Nevertheless, Las Casas experienced a conversion of the heart and did what many people prefer to avoid: He admitted he was wrong. He applied whatever light he had to the real-life issues of his day—and he took an active stand for justice.

After Las Casas died in 1566, his ideas continued to be criticized, even condemned as heresy. His influence did not disappear, though. He was among the first activists to affirm we are all children of God, with God-given rights to freedom. His current title—Servant of God—is the first step toward his possible canonization.

His life reminds us that following the will of God may put us in direct opposition to our society’s worldview. Even though his was a minority view, he knew his witness on behalf of Indigenous people was crucial to his vocation. To be Christian, after all, is to be countercultural. God is by our side when we stand against routine injustice, no matter how alone we might feel.

Las Casas’ witness to the dignity and rights of Indigenous populations makes me, a Mestizo Catholic of both Caribbean and Central American heritage, feel there is a place for me in the Catholic Church. Despite the church’s history of injustices and atrocities, Las Casas demonstrates that God is constantly at work. Even one voice, speaking up for justice, can be God’s instrument of change.

This article also appears in the April 2024 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 89, No. 4, page 33-35). Click here to subscribe to the magazine.

Image: Dani M. Jiménez

Add comment