Believe it or not, it can be hard to find a good seat at Sunday Mass. Unlike most churches I’ve attended across the United States in the past decade, where empty pews prevailed outside of Christmas and Ash Wednesday, St. Ita Church on Chicago’s far North Side is usually lively every Sunday—not necessarily packed but full enough that you don’t wonder where everybody went. Parish events such as barbecues, choral performances, workshops, and Bible studies are likewise flourishing, some running out of space weeks in advance. I’m speaking anecdotally here, but I would attribute this vibrancy to the success of a 2020 parish merger that brought together three churches—St. Ita, St. Thomas of Canterbury, and St. Gregory the Great—to form the new Mary, Mother of God parish.

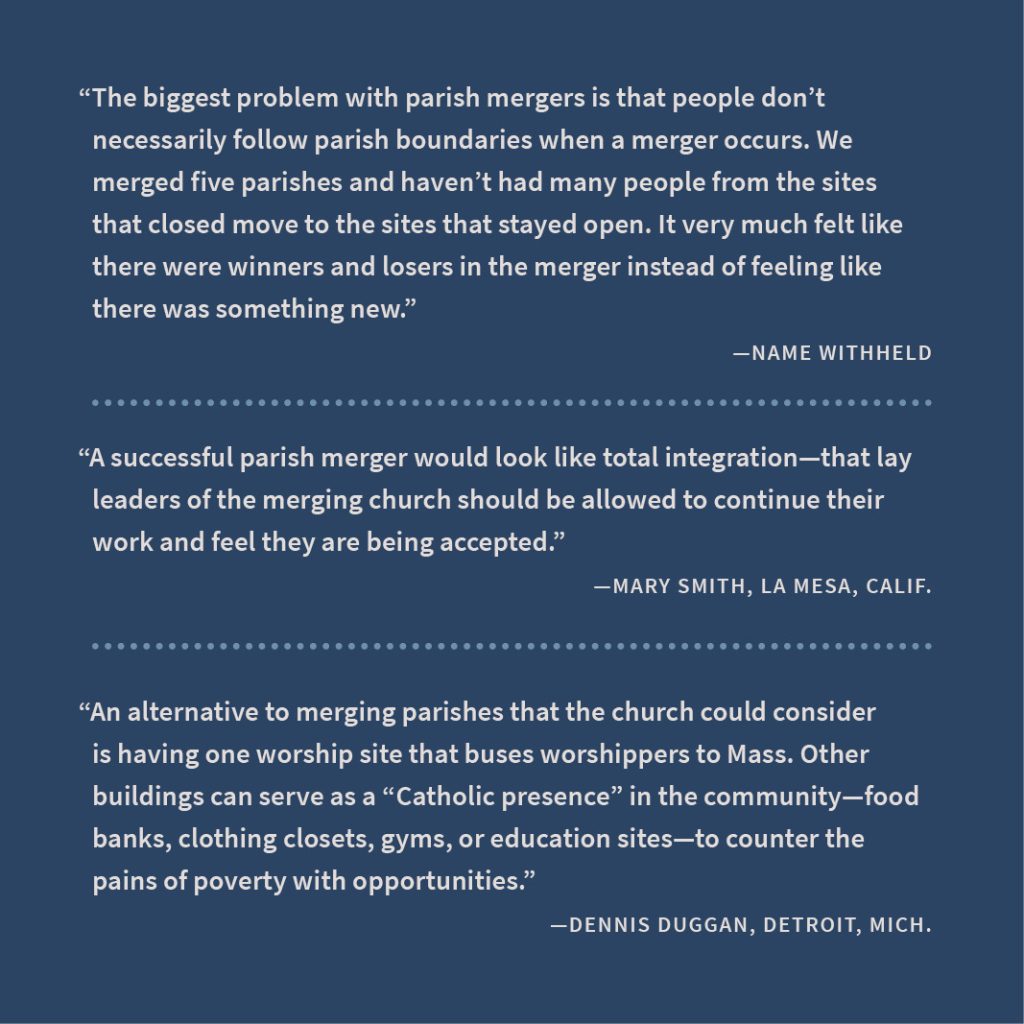

Of course, not all parish mergers are shining successes like this one (our merger went so well it was even profiled in Duke’s Faith & Leadership journal in 2023), but it does suggest that such success is not out of reach for parishes across the United States.

I don’t want to discount the genuine grief and hardship parishioners face on account of parish mergers and closures. Many have seen sacred places that held memories of cherished milestones shuttered. Others—especially the elderly, people with disabilities, and others with limited access to transportation—might now find it all but impossible to get to and from Mass as the center of their parish moved away from them. But as parish mergers and closures increasingly become the norm across the United States (as in the Archdiocese of Chicago, where the number of parishes has fallen by more than 100 between 2016 and 2022), it might be time to embrace their inevitability and find an intentional, optimistic way of writing this new chapter for U.S. parishes.

Much of the church leadership in Chicago and beyond has tried to strike this note. Take, for example, the archdiocese’s choice of the almost naively hopeful “Renew My Church” as a name for their campaign of parish mergers. But this seems to me to be little more than pretty window dressing.

In its vision statement, Renew My Church speaks of creating parishes that look beyond their church buildings to “bring the healing grace of Jesus Christ to the world” and that are “filled with engaged parishioners deepening their relationships with God.” This is all well and good, but how does a parish merger accomplish that? I doubt most Chicago parishioners are really convinced it does, and church leadership hasn’t built up the scaffolding necessary to show how it can.

But if done intentionally and thoughtfully, parish mergers can be in themselves a positive development for the church in the United States, because they offer a chance to build the preferential option for the poor concretely into the very structure of the daily life of the church.

While the problems most often cited for why parish mergers need to take place—shortages of priests and declining attendance—are certainly real problems, the underlying problem beneath these issues is that we have forgotten about the poor. To put it bluntly, the church is being gentrified.

To illustrate my point, consider two well-known Chicago churches: Old St. Patrick’s and St. John Cantius. Both are located in affluent neighborhoods on Chicago’s West Side and easily fill multiple Masses to standing-room-only every Sunday. Each is regularly staffed with at least a half dozen priests and offers a multitude of parish social events, groups, and classes. They can do this in no small part because Catholics from every corner of Chicago travel to them based on reputation: Old St. Pat’s is well-known as a hub for liberal and progressive Catholics, while Cantius is one of the only churches in the city that still celebrates the traditional Latin Mass.

This approach to parish membership is not something within reach for those who may already be struggling to find transportation to work or the nearest grocery store. Meanwhile, a church like St. Thomas of Canterbury, which eventually merged to become a part of my parish and had a large, mostly immigrant membership in a much less affluent neighborhood, struggled to find the resources even to offer Mass in the five languages commonly spoken by its parishioners.

I can’t speak to the situation in every city and town across the United States, but what’s developing here in Chicago might well be a two-tier system of parishes. Affluent (mostly white) Catholics flock to a few well-regarded parishes based on their liturgical, political, or whatever other preferences, and the donations follow. Meanwhile, the less affluent (and mostly non-white) Catholics are stuck in the shell of the old parish system, which decays around them as they struggle to support themselves.

Not only is this unsustainable, it also runs contrary to one of the most essential missions of the church: care for the poor and vulnerable. How can we even begin to think we can care for the poor when we abandon them in our own churches?

What is needed is nothing short of a revolution in how we understand our parishes. Parish mergers can be how we do that. Parish boundaries can (and should) be redrawn and expanded to include both the wealthy and the poor. The centers of these parishes can (and should) be moved into the areas of most need (think the St. Thomases, not the Cantiuses). In this way, rather than continuing to perpetuate our own Catholic version of white flight, what we give to our parishes can effectively go toward feeding the hungry, both materially and spiritually, because they will no longer be tucked away in far-flung neighborhoods. They will be at the church door.

Or we can allow parish mergers to perpetuate the problem. We can shutter struggling churches, tell their parishioners to figure it out, and exacerbate the problem. We can create the spiritual equivalent of food deserts.

This doesn’t necessarily mean shutting down long-beloved churches. But it does mean reevaluating what our churches mean to us. Is it the comfort of home—or the uncertainty of mission?

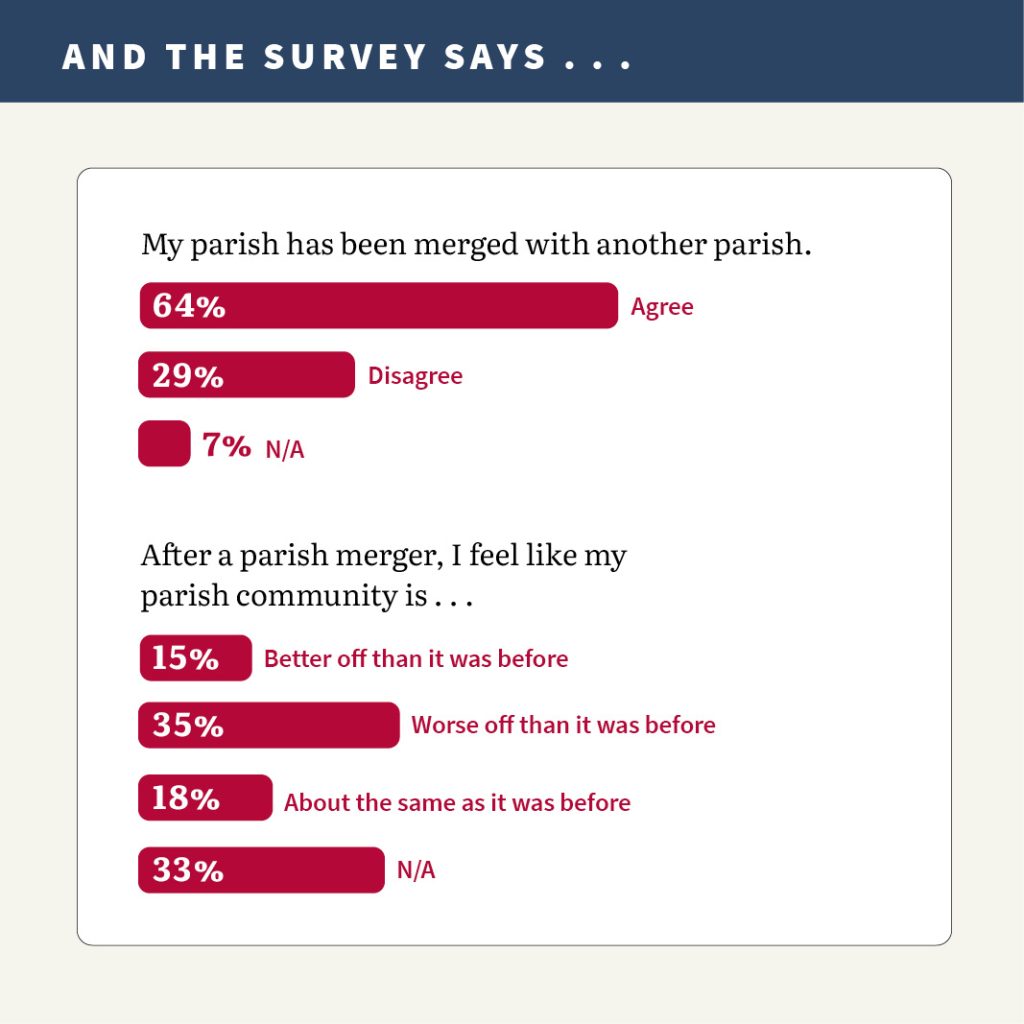

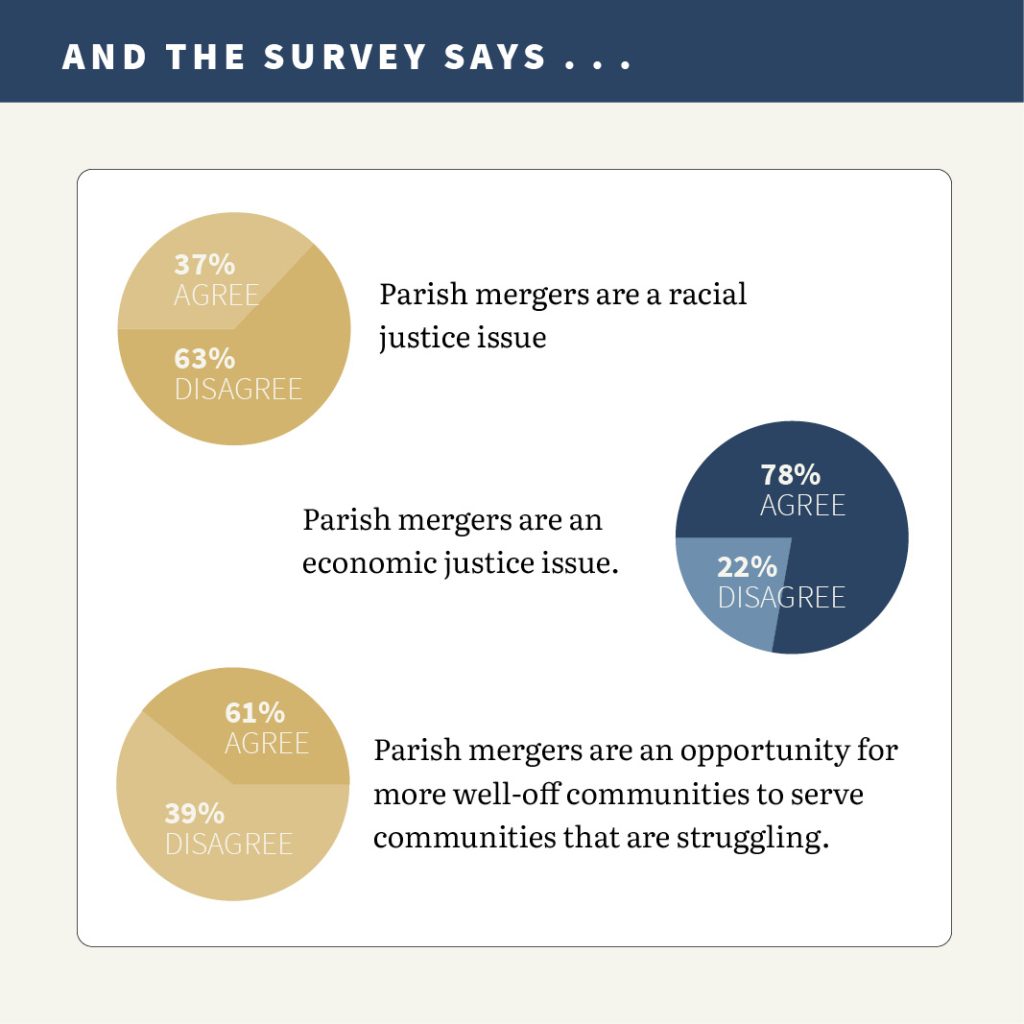

Results are based on survey responses from 42 uscatholic.org visitors.

This article also appears in the March 2024 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 89, No. 3, pages 32-35). Click here to subscribe to the magazine.

Image: iStock.com/MattGush

Add comment